The current Dabbler Book Club monthly choice is The Broken Road, the posthumously published third volume of the memoirs of the great adventurer and prose stylist Patrick Leigh Fermor. Here, Douglas Dalyrmple explains the author’s enduring appeal…

I’m deaf… That’s the awful truth. That’s why I’m leaning towards you in this rather eerie fashion.

That’s Patrick Leigh Fermor speaking to William Dalrymple in a 2008 interview conducted at Fermor’s home in the Peloponnese. Reading it five years ago, I was encouraged. I had come to Fermor late but like other admirers still wanted something from him: the promised third volume of his autobiographical trilogy begun in 1977 with A Time of Gifts. It wasn’t only Fermor’s self-awareness and humor at age 93 that encouraged me. It was the reported sighting by Dalrymple (no relation) of the “8in-high pile of manuscript, some of it ring-bound, and some in folders, on which was scribbled in red felt-tip: Vol 3.”

Any write-up of Fermor is required to note two things about the man. First, of course, is his journey on foot “from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople” begun in 1933 and recounted in the unfinished trilogy. Second is his two-year service behind German lines in Crete and his abduction of General Heinrich Kreipe, immortalized in what I’m told is the mediocre film Ill Met by Moonlight. Equally contributory to the Fermor myth, in my opinion, is his youthful romance with the Romanian Greek princess and painter Balasha Cantacuzene, the glory of whose name was matched only by the grandeur of her nose. Fermor and Cantacuzene lived together in a watermill outside Athens before the war.

Reading A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water is an education in print, and both will be mandatory for my children when they’re older. The journey itself served as an alternate university for Fermor, who had a knack for getting kicked out of school. Without too much posturing on his own behalf, Fermor becomes in these pages a sort of everyman on pilgrimage to Byzantium, his life a bildungsroman Childe Harold might envy. In every wintry starving solitude he is the object of unexpected charity; in every metropolis, the consummate flâneur; under every gothic arch, the questioning, curious student; and at the door of every fire-warmed baronial schloss, the adopted cousin of infinite welcome.

The Europe of Fermor’s books is long gone. It was on its way out even at journey’s start in ’33, the year that Hitler was made chancellor. The Rhine Valley, Vienna, Hungary, and Transylvania that Fermor describes from the dual perspective of youthful vagabond and literate soldier-scholar provide a lesson in the cultural and personal costs of war. It is a world composed of people, places, and ways of life about to be smothered under an awful weight of history. But Fermor’s prose is an amber preservative, full of golden glimpses.

About that prose: On first introduction you may experience a brief hesitation, like a bather stepping into a swift, cold stream. But then you give yourself to the current and are carried effortlessly, joyfully along. Fermor’s is not the kind of writing that makes for the convenient collection of aphorisms. It is not easily consumed in fits and starts. It builds almost symphonically, seductive and intelligent, vigorous and keenly observed (I’m still haunted by his description of a Sunday morning in Germany when the bells for mass pealed through the liquid atmosphere of a downpour: “We might have been in a submarine among sunk cathedrals,” he writes). His own late claims to the contrary, Fermor was never deaf.

Fermor died in 2011 at age 96, still a heavy smoker and still apparently suffering from his long-term writer’s block. And yet we’re finally getting volume three of his trilogy. Compiled and edited by Colin Thubron and Artemis Cooper from materials some of which predate the other two volumes, The Broken Road is available now to Fermor’s patient readers in the U.K. Pity us poor Americans who must wait until next March.

A timely review! we’ve had a lot of interest in The Broken Road as this month’s book club choice. Fermor is a terrific writer indeed

I’ve just started to read The Broken Road. After such great anticipation, I was disappointed with the first chapter; it didn’t sound like Patrick Leigh Fermor at all with its short, simple sentences! The second chapter, however, is pure PLF with its exquisite prose and wonderful digressions. I can’t wait to get back to it.

To anyone not lucky enough to get a copy from the Book Club, I’d say go out and buy one now. I think it might well prove to be the best volume of the trilogy.

I’m reading A Time of Gifts now, and have developed a theory about PLF, which I will present in Monday’s Diary.

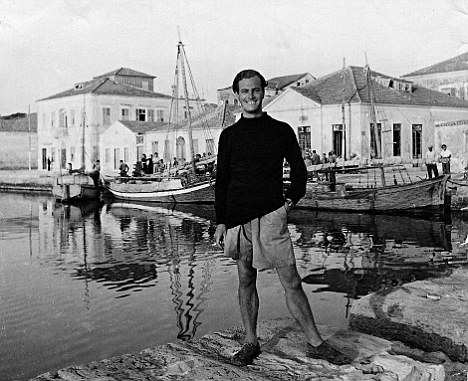

He looks like a young Jack Nicholson in that photo.