Football fan violence was far from an invention of the 1980s…

It’s one of the most extraordinary and tantalizing facts of our time. Take out all the estimated-to-be-drug-related activity out of the crime figures, and what you are left with are the gentle, pacific, Marpleian levels of fair-cop crime enjoyed in 1920s and 1930s Britain.

They didn’t enjoy them in the Edwardian period! Here’s Bolton v Glossop, Division Two of the Football League, 1908:

“No fewer than three players were sent off the field during the game, which was admittedly very vigorous indeed. Cuffe was the first sent off, and then a stand-up fight took place, with the result that Marsh and Hofton were ordered off. The referee was Mr. W. Gilgryst, and he reported the clubs to the Association, and also the players. He says, too, that the spectators were most rowdy and threatening during the greater part of the game. Mr. Gilgryst had to be escorted from the field to the dressing-room by the police and others, and was struck a severe blow from behind, the offender being taken in to custody. Furthermore, an official of the club was reported for using filthy language and for abusive conduct, while Bolton players complained of rough treatment. I am afraid there is serious trouble.”

(John Cameron writing for the Penny Illustrated Paper)

The best early stories of this kind always seem to involve fans of Preston North End. They knock railway officials unconscious at Wigan station in 1881. In 1884, they attack Bolton Wanderers players and fans at the end of the game. In 1885, they are involved in a stave fight with their colleagues from Aston Villa. In 1886, they take on Queens Park (Glasgow) fans at an unnamed railway station and two years later, there are tales of a hail of bottles..

In the 1890s, Preston step to one side and leave the field free for West Brom, who, at an away match with Nottingham Forest, invade the pitch and attack their own players!

It’s very hard to know exactly what is going on in stories like this. Part of the problem is that, contrary to what many might assume, we don’t really know much about who it was that was going to football matches. What evidence there is, is contradictory. One early Mitchell and Kenyon film of Nottingham Forest’s ground, scene of the Baggies triumph I’ve just described, shows a seated stand full of what are very obviously well-dressed, prosperous gentlemen and ladies. Other grounds that Mitchell and Kenyon feature really are all flat-capped, but most crowds are more varied and more difficult to judge. Ibrox was built in a genteel area and hoped to attract a loyal local following.

We do know that football clubs and authorities took measures to restrain crowd violence and regarded it as a problem – the “two-headed hydra” of the game, as one Victorian observer put it. Troubled grounds could be ordered closed, and matches moved. The Football League imposed a minimum entrance fee of 7d, pricing out the poorest (and, it was assumed, the most unruly). Most clubs charged even higher entrance fees for certain of their enclosures. Some seats at Old Trafford when it opened in 1910 were at a price point of several shillings.

It’s interesting to note that off-duty soldiers and naval men were granted free admission, on the premise that they would intervene to help out if trouble arose. That speaks of a belief in a cooperative, people’s policing in which the responsibility for order and control was more widely spread than it has become.

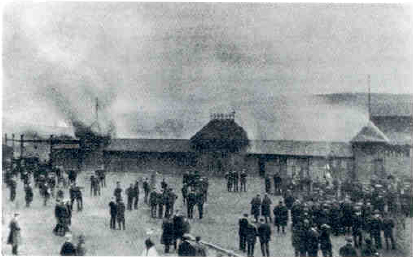

We also know that in common with all Edwardian crime measures, the amount of crowd violence declined in the years up to 1914. The climax seems to have been the great Hampden riot of 1909, in which 6,000 people participated, the pitch was destroyed and many parts of the stadium badly damaged by fire.

We’d see nothing like that again for another sixty years. It’s been said that the crime rates of interwar Britain are both the best any comparable country has ever enjoyed, and the hardest for any comparable culture to explain. So it was with football. Fan violence went away for forty years after 1919. And we’ve no real idea why.

If I had to guess I’d say two world wars had something to do with it. Maybe men who saw action, or who grew up in its shadow, didn’t have the stomach for it anymore. That kind of double bloodbath would leave people feeling pretty winded I should think.

Personally, there have been occasions when I’ve been kind of aggressively angry and by coincidence I’ve seen some vicious brutality either on the street or in the news and my aggression was replaced by a pretty queasy sense of dread.

It’s as though anger and violence feed on a lack of perspective, and vanish when you’re forced to take a broader view. I think the more universal our view the more pacific our demeanour, a la Buddhism etc. Aggression between nations certainly diminishes when people take a less partial, more global view.

Similarly, since the early 1990s, crime in the US has plummeted.

There are guesses aplenty, but no one really knows why.