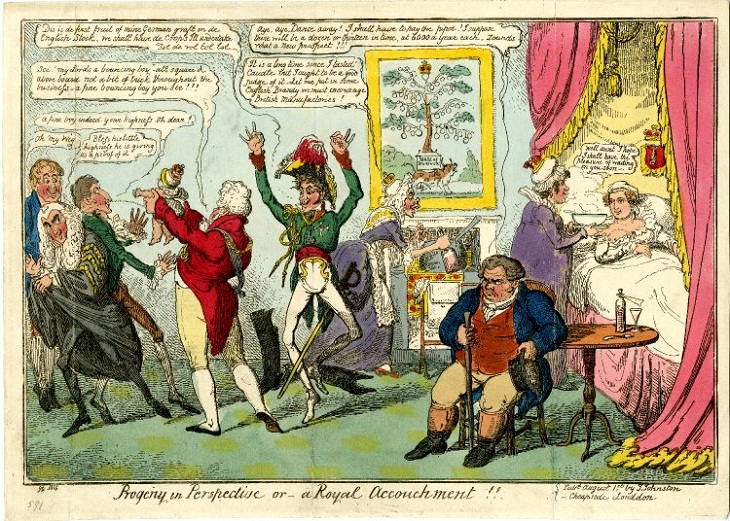

In honour of the new Princeling, Mr Slang is talking kids…

I love children, as Nancy Mitford put it so well, especially when they cry: for then someone takes them away. Mitford of course lived in Paris where they have a more robust attitude to those who have yet to acquire a civilized palate and where, only yesterday, a Parisienne, while gurgling with the best of ’em, on hearing that I was English observed, Alors M’sieur, la grande question: qui était le gran’père. Bien sûr, ce n’était pas Charles.

Slang, being among those who demand an article alongside uses of the word ‘baby’, averts its gaze from the current hysteria and finds a suitable representative in Mr S. who, as a diabetic, can only tolerate a limited sickliness. This is not to wish the newborn, who has rocketed straight into the entitlement charts at the number three slot, the slightest ill, but merely to preserve a decent distance.

But slang is nothing if not of the moment, so let us ponder a couple of examples of its infantine terminology. The oldest term, kinchin, springs from cant, the beggar tongue, around 1560. It comes from German Kindchen, a small child, and gives a variety of compounds. The kinchin co (co abbreviating cove, a bloke) is a child who has been brought up to thieving as a profession, an ‘ydle runagate Boy’ says Awdeley, and Harman adds ‘that when he groweth vnto yeres, he is better to hang then to drawe forth’. Grown older he regains his terminal -ve and as kinchin cove becomes a man, albeit short. The kinchin mort, the ever-moralising Harman again, ‘is a little Girle, the Morts their Mothers carries them at their backes in their slates, which is their sheetes, and bryngs them vp sauagely tyll they growe to be ripe, and soone ripe, soone rotten.’ Such a child might not be one’s own, what mattered was the pity it might excite and B.E. noted in 1698 ‘if they have no Children of their own, they borrow or Steal them from others.’ This has not changed: as in many urban rogueries, the modern city illustrates that beggary works with a well-honed repertoire. The 19th century added kinchin prig, a young thief, and the kinchin lay, thus kindly explained to Oliver by Fagin: ‘The kinchins, my dear … is the young children that’s sent on errands by their mothers, with sixpences and shillings; and the lay is just to take their money away.’ Alternative versions included the kid rig (rig: a con-trick) and to go upon the kid, to steal parcels from foolish errand boys who believed it when you promised to ‘hold on to them while you make another delivery.’ Given the duplicity, the term may be underpinned by the verbal form of kid, to tease, to deceive, which itself stems either from ‘treat like a kid’ or the synonynous cod.

The arrival of kid underlines the fact that by Fagin’s day it had become the dominant word, extending far beyond cant, though it played its role therein. And kid, as we know, is one of slang’s great stayers, elbowing its way into the mainstream long since and effectively replacing what, by implication, has become the middle-class prissiness of child. (Though young royals, even in the most hail-fellow of tabloids, do seem to escape ‘kid’, moving in popular eyes directly from the vaseline-lensed world of Start-rite and Blyton to ‘Randy Andy’ or whatever).

Kid, it appears, comes from the zoological name for a young goat. Middleton and Rowley used it in 1627, their line bracketing it with brat (and jeering at the impotence of one ‘lank suck-eggs’). By the 18th century it had been scarfed up by cant, and naturally described a youthful thief of either gender, trained up by a kidsman. If the father was already in the business, the infant villain was a kidwy (i.e, kid-wee) or kidling, though the latter came only to mean baby. In 1812 the knowledgable transportee James Hardy Vaux noted how ‘when by his dexterity he has become famous, he is called by his acquaintances the kid so and so, mentioning his sirname’, an ancestral precursor, perhaps, of such monickers as Billy the Kid or The Cisco Kid (though slang’s use for those is simply to rhyme with ‘Yid’. The Milky Bar Kid, however, is an Australian synonym for petty criminal).

The term widened, though faithful to its origins. Meanings came to include a member of a confidence team, a teenager (though that word still was far off), a form of address, and a reference to one’s younger sibling, ‘our kid’. By the late 19th century sex had arrived. The kid had become a catamite, whether as a tramp’s companion (though the main US term was gay-cat, even if for all the possibilities, there is no hard proof that this ‘gay’ was that of modernity) or the prison pretty-boy also known as a punk. A kid fruit, who pursued such company, was a synonym for the modern chicken-hawk.

Sometimes the sex was offered, as by the kid-leather, the young whore (leather meaning skin or more coarsely the vagina, which could be stretched or laboured.) More often it was sought after: by the kid-stretcher or kid stuffer, both of whom, in their paedophiliac obsessions, are known as kid-simple. Such usages predate or parallel the creepily infantilizing alternatives based on kid’s diminutive kiddy, which in such compounds as kiddy-porn or kiddy-fiddler have been around since the 1980s.

The term was launched with no such overtones. Kiddy as in child is in place by 1800; modified by ‘my’ it addressed a friend by 1850. The early 18th century has it as a fashionable, flashy young man, a rake, a pimp or a thief; and compounds it as rolling kiddy, a dandy-cum-thief, or a dandy who dresses like one. His girlfriend, noted Egan during Tom and Jerry’s trip to the East End’s All-Max tavern, was a kiddiess. Around 1850 it denoted a hat, fashionable among small-time but dandified thieves, featuring a broad ribbon passing through a large buckle at its front.

There are, of course, many more terms than this. To return to the cradle we have cockatrice (a ‘monster born from an egg’), the rhyming basin of gravy, Ireland’s scaldy, which otherwise refers to one who is bald, an ankle biter and a crumb-catcher. I shall leave you with New Zealand’s parcel from Paris. This presumably implies the usual ooh-la-la stereotype but that doesn’t usually extend to procreative intercourse. A parcel, on the other hand, is somewhat more substantial than a French letter.

Immortalised by Rab’s missus Mary-Doll, the Scottish wain “they wains is ma wains” has sadly fallen into disuse, wains were constantly greetin’, some say the stress caused by this racket is the reason for Glasgow’s sky-high murder rate. Or possibly them wains grow up to become petrol can wielding nutters.

The downside of the arrival of a qualifying royal sprog is that, in the not too distant future, there will be yet another sodding royal Hochzeit.

Hopefully at that time the post inbred and dysfunctional royal’s Hochzeit will have less bother and not require the services of Telemann’s Don Quichotte.

Brilliant as ever

Very silly question but is there any interesting root to ‘urchin’?

Far from silly, in fact eye-opening. I can only go to the OED and what they say is it comes from hurcheon, which is an old term for hedghog. ‘Etymology: < Old Northern French herichon, Old French heriçun, modern French hérisson < popular Latin *hēriciōn-em, late form of ēricius hedgehog.' It is also linked to irchin, also hedghog and with a similar etymology.

The link to a child comes on stream in 1556, prior to which, in 1525, it can be found meaning a hunchback. It could be used of any human being, not just a child, as in this cite:

1593 G. Harvey Pierces Supererogation 12 But Agrippa was an vrcheon, Copernicus a shrimpe, Cardan a puppy,..Cuiacius a bable to this Termagant.

My favourite use is to describe a mid-15 cent. sweet, so called from being made to bristle with almonds, etc. stuck over its surface

Germans use the same word ‘igel’ for both hedgehogs and sea urchins