Jonathon Green reviews a new edition of a groundbreaking work of Anglo-Indian lexicography…

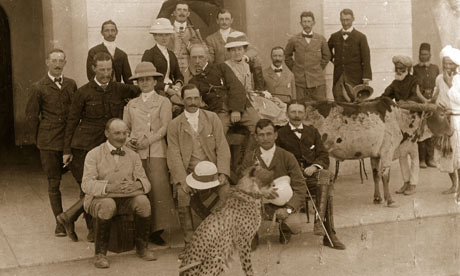

Hobson Jobson A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive was published in 1886. Its name comes from an Englished pronunciation of ‘Ya Hassan! Ya Hossein!’ as cried at the Shia festival of Muharram. Its authors were the polymath and voracious reader Henry Yule, scion of a family who had served John Company and a long-established ‘old India hand’ in his own right, and A.C. Burnell, a civil servant and specialist in Indian languages. They two had met in 1872 and soon determined to create their glossary. It was not the first of its kind, but the key lies in the term ‘discursive’. No such dictionary, focused on the British raj or otherwise, had ever been quite like it, even in the days when the lexicon was permitted to overstep the bounds of the encyclopedia.

The work took fourteen years and after ten Burnell was dead at just 42. Yule, the exemplar of the ‘gentlemen-officer-scholar’, survived publication by three years. The book was revised and expanded in 1903 by William Cooke, another Indian veteran. That edition has been regularly reissued, with a variety of introductions such as those by N.C. Chaudhuri and Anthony Burgess. In 1980 it was apostrophized by an Indian scholar as still ‘the only existing dictionary which closely approximates serious lexical work on Indian English.’ Now, 110 years later, we have a further revision, a ‘selected edition’ edited by Dr Kate Teltscher.

No dictionary, even such team-created efforts as the OED, stands in isolation: there is always a back-story, usually based on the prejudices and assumptions of its writer. Hobson-Jobson is about many things: notably its role as a linguistic expression of the nature of the raj and the relationships between the occupying British and those they ruled.[1] I have no brief as a historian; I prefer to consider the book in its primary mode; a work of reference.

Dr Teltscher has cut the original text by 50%. Where for instance the run from TEA to TIFFIN included 25 entries, there are now 12. We have lost among others TEE, a form of umbrella, TEHR, the wild goat of the Himalayas, and TIER-CUTTY, a toddy-drawer’s knife, but scholars need only look to the original edition if they require such references. Whether such excisions represent the work’s ‘fat’ is debatable, but the entries which Dr Teltscher has left us are indubitably ‘meat’. Five exhaustive pages on TEA with sub-headings to deal with varieties from Campoy to Young Hyson. Three pages on TEAK and a page-and-a-half on THUG with cites commencing c.1865 (that one in French). Nor has she only chosen the mainstream: we also get THERMANTIDOTE, a form of fan, TICCA, used with a noun, e.g. ticca doctor, to imply that the subject is not permanent but merely on temporary hire, and a disquisition on TIBET. Nor, elsewhere, has she shied from the coarse: here are BANCHOOT and BETECHOOT ‘terms of abuse, which we should hesitate to print if their odious meaning were not obscure to “the general”.’ The ‘general’ is better informed today, the words mean ‘sister-’ and ‘daughter-fucker’, though maderchoot, motherfucker, eluded the compilers.

The headword list deals on the whole in matters practical. We have JUGGERNAUT, as part of a religious procession, but no theocratic jargon, such as kismet or karma, though both were common in contemporary British texts. Nor, as noted by Salman Rushdie, is there wog. But then there wouldn’t be: the word, a sailors’ coinage which apparently landed on the Ratcliffe Highway around 1910, is not recorded until 1929,[2] though BABOO, to which the word supposedly refers, gets a column.

As to the authors’ style, that is left untouched – though the OUP have completely reset the text and what we get is very clean and legible. We are spoilt for choice but the entry for CANDY, in the sense of sugar, gives a good example of both the underlying learning and a style that, for all that Yule (as John Farmer was doing with his slang studies) sent him copies of the proofs, James Murray would never have been permitted at the emerging OED.

(3) CANDY (SUGAR-). This name of crystallized sugar, though it came no doubt to Europe from the P.-Ar. kand (P. also shakar kand, Sp. azucar cande; It. candi and zucchero candito; Fr. sucre candi) is of Indian origin. There is a Skt. root khand, ‘to break,’ whence khanda, ‘broken,’ also applied In various compounds to granulated and candied sugar. But there is also Tam. kar-kunda, kala-kanda, Mai. kandi, kalkandi, and kalkantu, which may have been the direct source of the P. and Ar. adoption of the word, and perhaps its original, from a Dravidian word = ‘lump.’ [The Dravidian terms mean ‘stone-piece.’]

A German writer, long within last century (as we learn from Mahn, quoted in Diez’s Lexicon), appears to derive candy from Cundia, ‘because most of the sugar which the Venetians imported was brought from that island’—a fact probably invented for the nonce. But the writer was the same wiseacre who (in the year 1829) characterised the book of Marco Polo as a ‘clumsily compiled ecclesiastical fiction disguised as a Book of Travels’ (see Introduction to Marco Polo, 2nd ed. pp. 112-113).

This is, I suggest, highly competent lexicography, and especially etymology. No-one could doubt the breadth of Yule’s reading nor the depth of Burnell’s knowledge. Eight languages are quoted. The supportive citations, two in Italian, start c.1343. But there is also that dismissive ‘wiseacre’. Our editors are unimpressed and keen to make sure their readers know it. No modern dictionary-maker, except perhaps Partridge, could have dared get away with such subjectivity.

Yule, writing his Introduction, laid out twin intentions: ‘My first endeavour in preparing this work has to make it accurate; my next to make it […] interesting.’ Neither he nor his collaborator would be disappointed in their modern editor. Dr Teltscher, who contributes an informative introduction of her own, plus an appendix of notes on certain foreign terms, does them proud and in so doing displays her own expertise. Deliberately or otherwise Hobson-Jobson, as well as being a unique work of reference to be consulted, was always a book to be read. This new, selected edition makes that reading even more of a pleasure and if we have lost certain terms, then we have hugely gained through the addition of Dr Teltscher’s skills.

[1] one such story is the near-total exclusion of examples from Kipling who might have been seen as a shoo-in and was among the many positive reviewers. Cooke’s 1903 revision managed to slip in 11 cites, but the 1886 had none (in fairness these were relatively early days for the author’s celebrity). However this was not oversight: it appears that Amy Yule, the author’s daughter, disliked him, and he had possibly insulted one of Burnell’s heroes. Thus, believe me, are citations chosen; even now.

[2] F. Bowen Sailor’s Slang: ‘Wogs, lower class Babu shipping clerks on the Indian coast’

I love all those indian words like kedgeree, gymkhana and blighty

There was a post a couple of years ago, I cannot think where, by a professor who had been brought to New Delhi as aide to a cabinet minister. Someone of long experience explained to him that the ABC of administration is actually the “BCD”–one of the “choots” referenced above must be the prefix. The professor, after some period of obstructionism by the permanent staff, deployed the epithet, and got results. It was not, he said, that anyone was shocked to hear, but rather that it was understood that anyone privileged to use the term had serious mojo.