What can we learn from a composer’s very first work? Mahlerman investigates…

Not the first work composed, but the first work published, the Opus 1 has held a peculiar fascination for musicians down the years. Sometimes the work (opus), even if penned by one of the great masters, is perfectly serviceable but gives no clue to what might appear later (Beethoven’s E flat piano trio); sometimes the piece is so lacking in interest that you wonder why the composer bothered publishing it in the first place (Chopin’s Rondo Op. 1); others are so good that you can’t imagine why they are not performed every week. A good example of this last is the First Piano Concerto of Sergei Rachmaninov. The second and third concertos are all over Classic FM like a rash (allegedly), but is the F sharp minor Opus 1 such a dud? Today, so that you don’t have to, I have scoured the catalogues for worthwhile pieces that, judged by the highest standards, could well carry a report card saying ‘could do better’. The fact is that the quartet below pushed on and indeed did do better, spectacularly in a couple of cases.

The rather patronizing phrase ‘Papa Haydn’, coined in the nineteenth century, has lingered on to infect our own view of Josef Haydn, by any sensible measure one of the greatest composers ever to draw breath. Yes, he was the father of the symphony, and the one hundred and four that he wrote all but span his creative life. Perhaps, save for his unquestioned genius as a musician it is his very normalcy, his ordinariness, that bars him from the very top rungs of the ladder? A constantly serene nature behind a plain visage, he married in haste, repented at leisure, but consoled himself with a string of affaires de coeur ; he was without malice and, though ambitious, he strove only to improve himself – and in striving thus, he achieved an aesthetic perfection that represents a blueprint for the classical artist that is matched by no other composer before or since. He composed in all forms, but perhaps it is the vast panorama of his 68 wonderful String Quartets, the first really great body of work to be written for this combination of instruments, that will ensure his immortality. Haydn’s first published works were the six string quartets that make up his Opus 1, and from that set we hear the warmly human beauty of the Adagio third movement from No 1 in B flat major ‘La Chasse’ composed around 1760, when the composer was not yet 30. I am still trying to work out the significance of the colour-shopped drawings by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec that attend the music on this video or, for that matter, the link with Haydn – and I therefore suggest that, for maximum enjoyment, you close your eyes until the hushed close.

Haydn died in 1809, the same year that Felix Mendelssohn was born into an affluent Jewish banking family in Hamburg. ‘Papa’ was born into poverty, and as a young man experienced penury and destitution, a fact which contributed in no small measure to his relatively late start as a composer. Mendelssohn, a beautiful child, has been compared favourably with the young Mozart in his precocity as an instrumentalist and composer – his Octet for Strings and overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream are both jaw-dropping masterpieces. The fact that they were produced by a sixteen year old is, to this day, almost unbelievable. Haydn started at a modest level of competence and gradually became greater; Mendelssohn began in a heavenly burst and gradually subsided into heaviness and pomposity. The composer’s Opus 1 is the delectable Piano Quartet in C minor, composed when he was just thirteen, from which we hear the serene second movement Adagio.

Karol Szymanowski was perhaps the most original composer that Poland produced after Chopin, and before the 20th Century fashioned Penderecki and Lutoslawski. All Poles revered Chopin, quite naturally, and Szymanowski’s enthusiasm was boundless too – until a study period in Berlin exposed him to the post-Salome Richard Strauss and the impressionism of Debussy. This period of ‘influence’ produced the marvel that is his opera King Roger, and the complex, hot-house world of his Third Symphony and the magical First Violin Concerto. But it is Chopin’s influence that pervades the nine Opus 1 Preludes, composed at the turn of the century when the composer was a teenager, and published in 1906. We hear the last three of these today, played by the under-appreciated English pianist Martin Jones.

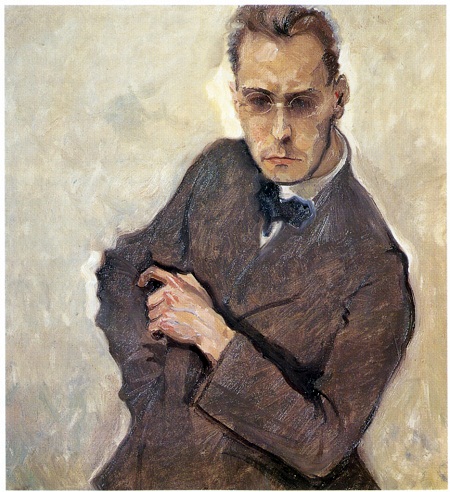

Just the mention of his name sends ‘music lovers’ running for the hills – brought up, as many of them are on free flowing melody they search, often in vain, for even the smallest evidence of it. But the sound-world created by the Austrian pioneer Anton von Webern was absolutely new and unique, a microcosm of delicate, ephemeral, pointillistic sounds – and silence, the sound of silence. His teacher Arnold Schoenberg had spoken about Klangfarbenmelodie, the so-called ‘melody of tone colours’, and this idea inspired Webern, like a great saucier reducing and distilling, to compact and reduce the organized ‘tones’ of his imagination, eliminate rhetoric, and follow his own dictum that ‘Art must be simple’. Dabblers may find a better explanation than this, but I would liken it to discovering a new language – that perhaps sounds alien. To our ears Portuguese, say. Then you study (and listen to) the grammar, the syntax and, after a while, the mists begin to lift. One fact makes this task easier – the music’s brevity. Last month in ‘Lust In The Dust’, I mentioned that you could listen to all of the music of Spain’s greatest composer de Falla in a day. All Webern’s oeuvre can be played through in an afternoon, and some last for less than a minute (‘Bravo!’, some would say – but not I). The work of Webern’s that was to lift the scales from my eyes was not one of the later ‘dazzling diamonds’ (Stravinsky) of his maturity, but in fact his very first published work, the Opus 1 Passacaglia from 1908, when the composer was just 25. It is probably the best introduction to this often puzzling artist, as the overall texture is lush and, yes, even romantic. But amongst the swirl there are fragments of the ‘compression’ of sound that, a few years later would grip his imagination. An altogether marvellous piece. The haunting (and haunted) pictures here are by another Austrian, the contemporary of Webern, Egon Schiele, who died in the flu epidemic of 1918, three days after his wife. He was 28.

Marvellous as ever, MM. That Webern is actually quite accessible, I thought. I was expecting the unlistenable, but not at all.

I every time spent my half an hour to read this blog’s articles or reviews daily along with a cup of coffee.

I read this article fully on the topic of the comparison of

most recent and previous technologies, it’s amazing article.