He was the bard of Chicago and he tried to steal Simone de Beauvoir from Satre… Mr Slang introduces the man behind The Man with the Golden Arm…

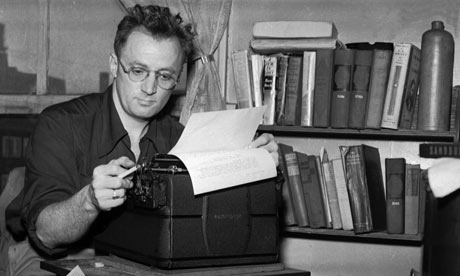

As Hamlet put it, look here upon this picture. And see before you, dare I attest, a proper writer: specs, work-shirt, hair a little messy, fag on, typewriter, shelves of dictionaries, what looks like an emptied bottle of genever. Or at any rate a proper American writer: none of your epicene devotees of literary nature study here. No dreary solipsistic adulterers waltzing around their Hampstead pinhead. This is a city boy. This is a slang boy. This, because it possible that you were wondering, is Nelson Algren (1909-81), bard of working-class Chicago and best known for The Man with the Golden Arm, the story of the junkie-cum-poker dealer Frankie Machine, published, feted and en-prized in 1949 and butchered into a second-rate Sinatra vehicle by Otto Preminger six years later.

I have been reading a good deal of Nelson Algren recently. I read a good deal of Nelson Algren when I was researching the big dictionary but recently I found that despite what I assumed I had not read all and because a publisher called Seven Stories have been adding to the in-print availability of his work my oft-repeated prayer – why doesn’t the deeply wonderful X, write something new? X having invariably been long since dead – has for once been answered. There is always a fear with this kind of thing – see for instance some of the posthumously issued works of Roberto Bolano or David Foster Wallace or indeed Jimi Hendrix – that rather than the taut echo of crystalline creativity we shall hear instead the dull scrape reverberating from the depths of the bucket, but while not everything is of the man’s best, it is on the whole pretty good stuff. It may offer some of the pieces he knocked off for the ‘men’s magazines’ (Playboy, Dude, Cavalier) of the 60s – an unregenerate, yet always unaffianced lefty he had fallen foul of the knuckle-dragging Sen. McCarthy and his career suffered accordingly – but even these are not without wit. In any case one gets the feeling that publishers, not to mention Hollywood, would always have found him an awkward, uncompromising cuss. Most important it also gives us the chance to see a sizeable chunk of Entrapment, the unfinished novel – another plunge into the world of the lost – that would probably have been his final triumph. Seven Stories have also put out his literary apologia, Nonconformity, which was written at the height of his fame, but in its excoriation of America, was left unpublished until 1996. The Feds, fearing the possible influence of so celebrated a writer, had leant successfully on his publisher, Doubleday, and all was silence. It still reads well. America, like the rest of us, has not changed that much, other than in its technology.

This is called Heroes of Slang but as I do in many things I pass the responsibility of choice to that abstract doppelganger I call Mr Slang. As for me, I don’t do heroes but if I can allow for one apostate Jew, Lenny Bruce, then I offer another: which other is Algren, born Abraham, and the grandson of a Swede who had voluntarily converted from Lutheranism. I cite him over 1,100 times, which testifies to at least one aspect of his importance. About a quarter had never been recorded before. A man of the margins – his literary reputation among them – he decided early on that recording as accurately as possible the language of the streets was as near as one could get to the character of those that spoke it, and that those speakers, those who live nearest the gutter, were those most worthy of chronicling. He saw ‘no purpose in writing about people who seem to have won everything. There’s no story there… Why write about happiness? There’s nothing there…no conflict, no catalyst for discovering anything about humanity.’ Instead he wrote of an America that existed ‘behind the billboards and comic strips’, and noted that ‘a thinker who wants to think justly must keep in touch with those who never think at all.’

This was not empty romanticism: the ‘community leaders’ of those he described regularly sought to have his portraits of those they claimed to represent effaced from the public’s eye, and his tales, whether short stories of bums riding the rails, or the junkies, alcoholics, whores and assorted losers of the urban mean streets were uniform only in their lack of any vestige of a happy ending. His own life was difficult: he drank, gambled and whored and like other flawed semi-stars – George Gissing, Patrick Hamilton – he had a problematic relationship with a prostitute, compounded in his case by her heroin addiction. He also tried to take Simone de Beauvoir from Sartre, but she, unsurprisingly, wasn’t about to be ‘taken’ by anyone and made her own choice, which remained bounded by the Left Bank. He favoured the downtrodden but like the slang they used and he faithfully wrote down he seems devoid of conventional morality. As a young man he did time for stealing a typewriter – symbolism if you must – and while devoid of military ardour used World War II to benefit from one of its profitable GI black markets. (Later, writing about Vietnam, he apparently hoped to capitalise on Saigon’s corruption but by now he was too much of an outsider). Given the choice he opted for the circles of which he wrote over those that judged the prize-worthy. He flourished briefly after Man…, granted a brief acknowledgement at the edges of respectability, but faded: his last decade was spent writing for Playboy and other, lesser ‘men’s magazines’, and he knew that in that company one wrote what an audience wanted even if he could never disguise his anger. He failed to complete his last novel, which from what survives suggests that it might have been his best.

Algren remains on the margins. When I mentioned to US pals that I had thought of pitching a biography they seemed bemused, even contemptuous of so absurd a conceit. There were intermittent acknowledgments but the establishment remained at a distance even if were some prizes towards the end, and after he died fans tried to rename Chicago’s Polonia Triangle, the area of which he wrote, in his honour. The locals said no. I doubt that he would have much cared. It is hard to believe he took such things that seriously. Perhaps because more than most (and again I tip a hat to Vollmann) he walked as well as talked. Look here upon this picture, requested Hamlet. Then continued: And on this:

The fact is Algren was poleaxed by what he considered to be De Beauvoir’s betrayal and it was downhill from there. His vicious review of her memoirs is a case in point, calling her the lady who never shut up – he never, ever forgave her. Of course, Simone would never have settled down as a Chicago hausfrau nor did Algren feel comfortable in Paris literary salons, but this was his “grand amour perdu”. I had hear Johnny Depp and Vanessa Paradis were going to make a movie of their affair but have had no updates.

Books Now!

It’s been many years since I read her autobiography, which left me thinking she was one of the most horrid women of the century, but I was left with the impression he was just a rest stop on her futile lifelong quest to make Sartre jealous. Politically it was interesting to see the clash of domestic and European anti-Americanisms they represented, which, if memory serves, became quite bitter. He railed against plutocratic capitalism as having betrayed the glory of the Revolution, while she thought the whole project was rotten from the getgo.

Algren gets a fair cameo in William Styron’s essay “Transcontinental with Tex”, about Styron’s and Terry Southern’s train trip to Los Angeles. No deep insights, but worth a look, it is collected in the book Havanas in Camelot.

If anyone fancies something more substantial, I offer this link to a recent biographical essay on Algren:

http://www.believermag.com/issues/201301/?read=article_asher

Jonathan–we have been working for the last 4 years on a documentary on Algren, and we are almost complete. Come check us out at montrosepictures.com and facebook.com/algrenthemovie. Algren needs to be known much more widely than he is, and we’re always glad to find fellow followers!

It wasn’t de Beauvoir’s autobiography that Algren slammed, it was her 1956 novel The Mandarins, where she fictionalized their romance (along with everything else). One key aspect of Algren’s aesthetic that sets him apart from contemporaries like Saul Bellow (they were on the WPA together) is that Algren NEVER wrote fiction about himself. His late “new journalism” phase (forced on him by economic necessity) is different, but in his short stories and novels and poetry, there is no sign of the Writer Struggling To Write About This. No, he wrote about and for people who, as Frankie Machine put it, planned to “get a lib’ry card” one day.

And Algren was a king of slang. Aces, bannegers, monkeys on backs. He heard and wrote the speech of the streets.

Great post, thanks.