Lance Armstrong’s Oprah confessional has put cycling on the front pages again for all the wrong reasons. But he’s hardly the first rider to come to a bad end. Death, drugs, sex and madness – here are three cautionary tales from cycling’s rogues gallery…

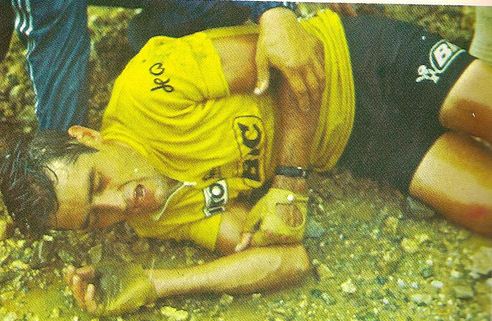

Tom Simpson

Dubbed ‘Major Tom’ by the French press, Simpson (above) was the first British rider to wear the yellow jersey, and won the world championship in 1965. The son of a Durham miner, he played the part of the English gent with relish when on the other side of the Channel, dressing up in a bowler hat and suit, complete with rolled umbrella, for the benefit of French reporters. One of the era’s most respected riders, he finished sixth in the 1962 Tour and also won the Milan-San Remo, Paris-Nice, and Bordeaux-Paris races – the latter a hellish 350-mile non-stop slog which began at 2:00am, lasted about 15 hours before reaching the capital, and included long stretches of motor-pacing behind miniature motorbikes known as “dernies”.

But how did Simpson maintain the pace in an era when doping was rife in the peloton? That became hideously apparent during the 1967 Tour when he keeled over and died on his bike in furnace-like heat near the top of Mont Ventoux. Doctors found amphetamines in his system and team-mates recalled how he had been drinking brandy – snatched during one of the ‘cafe raids’ which riders depended on for sustenance – before the climb. Such was the diet of champions in an era now fondly remembered as a cycling golden age. The spot where Simpson died is now the site of a granite memorial, piled high with water bottles, tyres, and cotton cycling caps left in tribute by passing riders.

Luis Ocana

Fated to belong to the same generation as Eddy ‘The Cannibal’ Merckx, Ocana’s life story perfectly epitomises the old blues line – if it wasn’t for bad luck, he wouldn’t have no luck at all. Born dirt-poor in central Spain, Ocana’s family moved to France when he was just six – and he later raced over the same Pyrenean passes his father had trudged over in search of work. Ocana’s rivalry, perhaps obsession, with Merckx was so all-consuming that he named his dog after the taciturn Belgian. “Obey, Merckx, I’m your master, your boss,” he would tell the hound. But when Ocana had his best chance to beat Merckx, in the 1971 Tour, disaster struck. With Ocana in yellow, seven minutes ahead, Merckx attacked on a treacherous Pyrenean descent and crashed into a wall. Ocana tried to avoid the Belgian but crashed himself.

But while Merckx recovered and rode off, Ocana was hit broadside by another skidding rider and left screaming in agony by the side of the rain-drenched road (see picture above). Ocana ended up in hospital, Eddy in yellow – again. Ocana won the Tour for himself, in 1973, but Merkcx wasn’t riding that year. On retirement, Ocana struggled to start his own vineyard business, was diagnosed with Hepatitis C, and took his own life by shooting himself in May 1994. Some of his ashes were supposedly dissolved in whisky and drunk by a prostitute in a Madrid bordello. “One thing that he did beat Merckx on, well, two in fact, were whores and drinking,” his friend Juan Hortelano recently told Rouleur magazine. Unfortunately they don’t give out yellow jerseys for that.

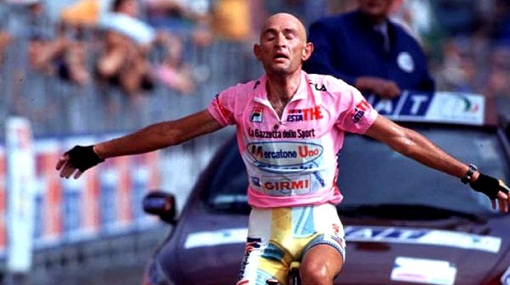

Marco Pantani

Sporting a shaved head, bandanna and ear-ring and going by the nom de guerre of ‘The Pirate’ – or alternatively ‘Elefantino’, for his outsized ears – Marco Pantani cut a suitably garish figure in the day-glo world of 90s cycling. The last rider to win the Tour and the Giro d’Italia in the same year, the Italian’s style was based on sudden, dramatic accelerations in the mountains, throwing races into chaos with attacks which were sometimes signaled by his flinging his bandanna to the ground in a gesture of simultaneous contempt and disgust. With the other riders, or with himself? Pantani’s Tour win, in 1998, came against the background of the ‘Festina affair’, when the race descended into farce following the expulsion of the eponymous team, whose soigneur had been arrested with a car full of steroids and EPO.

Pantani claimed the Tour may have been the cleanest ever, because of the fear of the police after the Festina raids. But the truth seems to have been revealed the following year, when Pantani was expelled from the Giro while in the leader’s pink jersey for an excessive hematocrit reading – taken to be an indicator of EPO use.

A comeback in 2000 saw him dueling Lance Armstrong on Mont Ventoux, before pulling out with stomach problems. That was his last Tour appearance. The final years were marked by a ‘my cocaine and hookers hell’-style descent into madness. Pantani had plastic surgery to pin back his ears, and was found dead in a cocaine-strewn Rimini hotel room in 2004. So ended the long, lonely road of a man Armstrong once said was more like Salvador Dali than a conventional bike rider. He still holds the record for the fastest ascent of the Tour’s iconic Alpe D’Huez climb.

Loved this!! Trying to remember the book I read that deals with Tom Simpson in great detail, some chap cycling the your de France route – French revolutions or something…anyway, the mind boggles that at any point in the race someone could consider drinking brandy!!! Yikes

A very funny book.

Aye that’s the one!! Fun little read

Not sure about that point in time when tour organisers eyes became blind and this is the crying shame here. Had they put common sense before greed (or vainglory), performance enhancing drugs would have been a minor problem. British time trialling and mass start, or road racing as it became, was in the late fifties a strictly amateur sport. Not so track and grasstrack sprinting where there was a ‘semi-professional’ element requiring a different licence, leading to the loss of amateur status and the license, anyone racing on road and track was stuffed. Mainly a working class sport many of the clubs were loosely trade based, the Tyne Electro was made up of group of electricians from Parsons and Vickers. The idea of using drugs would have been anathema then, even using the gym was initially thought to be slightly poncey. Our hero was Jacques Anquetil and following road racing in Europe was a pain, week old copies of L’Equipe or the odd radio coverage being the norm. Brought up in this atmosphere I often wonder what it was that turned Simpson to the dark side, lack of restraint?

Anquetil, I hope, would have been horrified at the thought of drug use preferring a night on the town prior to a day in the saddle.

I was a real Tour enthusiast in the 90s and I loved Pantani. Finding out he was a cheat killed cycling for me long before Armstrong could do it, and I gave up watching … until Wiggo restored hope!

A BBC documentary of a few years ago depicted Simpson as one of the most single-minded, brave, and utterly determined riders ever to mount a racing bike, and it appeared to be those qualities, in addition to amphetamine, brandy, and whatever else, which ultimately conspired against him winning the greatest race of all, and instead caused his death. His cycling philosophy appeared to be: if there’s an opening to go to the front, don’t hang about, take it; no sodding around in the peloton. A 1967 version of Dave Brailsford would probably have preached the tactical approach to Simpson, day-in, day-out, possibly to little avail. But then Simpson was riding in a very weak British team. I suppose he saw that the only way to ultimate victory was to strike out alone from an early stage. There is, of course, no justification for the drug taking, even though, as you state, Ben, it was rife in that ‘67 peloton, so to some degree there was a weird sense of equality between the riders. I feel a combination of wonder and horror when contemplating the thoughts that must go through the mind of a great athlete like Simpson, having already covered 130 km from Marseilles, as he arrives, in the midday furnace, at the beginning of the climb of Ventoux. It sounds like the stuff of nightmare.

Far less of a nightmare was to stand at the top of our road on Sunday mornings in the mid 1950s and wait for the great Reg Harris to come past on a training run, at speed, and not so much as a glance in our direction even though we shouted ‘Hiya Reg – how about an autograph?’ We then went back down the avenue and waited outside Number 20 for a late teenage Laurence to emerge with his Claud Butler, all pale blue and gleaming (the bike, not Laurence): “Where today, Laurence?” “Oh, only mid Wales!” Wow!

just realised how much the weary Tom Simpson in that photo looks like the knackered mute cyclist in Belleville Rendez-Vous – anyone else know what I mean?

http://www.theoneliner.com/img/sm/030904_bellevillerendezvous03.jpg

Thanks for the comments. I passed up a chance to buy a DVD of that Belleville Rendezvous at a bike swap meet here in Brisbane last year … spent my money on some Campagnolo hubs instead. That was the first time I’d heard of it but since then everyone’s been mentioning it. Memo to self…