Anyone who has suffered writer’s block might take consolation from the life of John Ferrar Holms. In the first of two posts, Jonathan Law introduces perhaps the least productive ‘writer’ in the English language…

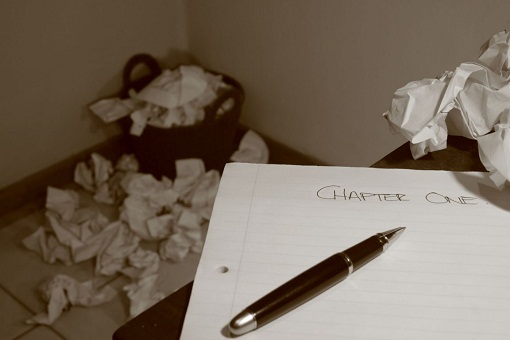

On a murky day in June, Mark Pack wrote feelingly about the miseries of writers’ block – of self-doubt, procrastination, and hours spent sweating it under the evil eye of the cursor:

Oh how I learned to hate the blank screen, its emptiness mocking my inability to turn years of accumulated knowledge into even mere scraps of disjointed sentences. No thought seemed the right commencement. No premise the correct starting point. No anecdote a relevant prologue.

Just the blinking cursor …

Now, if there’s one subject on which writers tend to be eerily lost for words, it’s this one – the block. Two attitudes seem to prevail, neither of which makes for verbosity. On the one hand, there’s a superstitious dread of the whole topic – something like the old fear of naming a demon aloud, in case the mere saying becomes a summons and all at once the nasty thing is squatting on your shoulder. On the other, there’s a brusque scorn for any scribbler so weak-minded as to credit such stuff. Call yourself a professional? Then stop your blather and think on Trollope with his stopwatch and his 250 words every 15 minutes. After all, those in other walks seem to get through the day without this sort of fuss. Chiropodists’ block? Ambulance drivers’ block?

I suppose it all goes back to the Romantics, with their interest in the psychology of creation and the view of inspiration as something wayward and fleeting (Shelley: “A man cannot say, ‘I will compose poetry’ ”). The idea that creativity springs from mysterious, hidden sources has as its flipside the idea that such sources may inexplicably dry up. So we find Wordsworth on the cusp of middle age, mourning a power that already seems to be deserting him:

The hiding-places of my power

Seem open; I approach, and then they close;

I see by glimpses now; when age comes on,

May scarcely see at all …

And then there’s Coleridge, of course – a man who found a strange sort of vocation in his failure to live up to the promise of his early genius. The predicament of the blocked artist has rarely been summarized with such fearful concision as in this entry from Coleridge’s Notebook, dated October 30, 1800:

He knew not what to do – something, he felt, must be done – he rose, drew his writing-desk before him – sate down, took the pen – found that he knew not what to do.

***

If I ever get that blocked feeling, I tend to consider the strange case of John Ferrar Holms – both as a consolation (things have never got that bad) and as the most awful of warnings. Probably you’ve never heard of Holms (1897-1934) and probably that’s only as it should be: he has given the world little cause to think of him. If he has any claim to fame, it is the sad and singular one of being quite probably the least productive writer in the English language – an odd status that raises the question of just how little a man can write and still be a ‘writer’. Although widely considered a genius in his time, Holms comes down to us as a mere footnote in the biographies of his friends and lovers, with even the vast lumber room of the Internet retaining barely a trace of his 36 years on earth.

It wasn’t supposed to be that way. As the 1920s wore into the 1930s, those who knew Holms best rarely faltered in their belief that this strange, obsessive man – a manic perfectionist who seemed to regard even the most universally praised writers as sloppy underachievers – was hatching works to make future ages gawp. To his boosters, he was no mere literary hopeful but a being whose gifts of intellect and expression put him up there with the greats: a man to be mentioned in the same breath as Shakespeare or Plato. The poet Edwin Muir, who was never one for hyperbole, stated quite simply: “Holms was the most remarkable man I ever met” – and it’s worth pointing out that Muir had met most of the big English writers of the day. To Muir, Holms possessed a mind of such preternatural strength that it seemed to belong to an unfallen order of creation:

His mind had power, clarity, and order, and, turned on any subject, was like a spell which made things assume their true shapes and appear in their original relation to one another, as on the first day.

Peggy Guggenheim, the heiress and art collector, was another who considered Holms by far the most extraordinary man she had known – again, quite something when you consider that her lovers (to say nothing of her wider circle) included Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, and Samuel Beckett. According to Peggy, who survived a stormy six-year relationship with Holms, being in his company “was equivalent to living in a sort of fifth dimension”. Others to fall under the spell included William Gerhardie, Alec Waugh, and the radio pioneer Lance Sieveking – who believed that if Holms could have overcome his demons he might have been “a literary figure as familiar as any man who ever wrote.”

Well, perhaps, maybe, possibly, who knows? There’s no way of telling. For as it turned out, Holms’s complete works would consist of one short story, a few critical essays, and a handful of unfinished poems.

***

History is, of course, not short of figures who managed to enthral their contemporaries in ways that later generations struggle to understand. More often than not, the explanation has something to do with brilliant talk (Coleridge again) or a charm or charisma that just doesn’t make it to the written page. In Holms’s case, this seems to be at most partially true. Although Alec Waugh described him as “a brilliant talker”, others disagreed, noting that he hardly ever finished a sentence before becoming lost in the maze of his own thoughts. Similarly, Holms’s personality seems to have been lacking in the finer points of attraction, being at once fiercely brooding and oddly passive. In Edwin Muir’s view, “Holms had hardly any personality at all; when he impressed you it was by pure, uncontaminated power”.

It is in the accounts of Holms’s appearance that we get a real clue to the spell that he cast on others. At well over six foot, with a broad chest and shoulders and a mane of flaming hair, Holms had the sort of looks that ought to belong to literary lions but too rarely do. With his sad eyes, sensual mouth, and the small pointed beard he liked to twirl when thinking, people were put in mind of a Spanish grandee, an Elizabethan courtier, or a character out of Dostoevsky: for her part, Peggy Guggenheim claimed that he “looked very much like Jesus Christ.” Alec Waugh noted simply “He was how I expected a genius to look”, while Edwin Muir describes strangers trooping to his lodgings in Prague, just to set eyes on the melancholy red-haired giant.

Indeed, Holms seems to have had a peculiar physical quality that went well beyond his magnificent physique. This is an aspect of his friend that Edwin Muir puzzles over at length in his Autobiography:

In his movements he was like a powerful cat; he loved to climb trees or anything else that could be climbed and he had all sorts of odd accomplishments; he could scuttle along on all fours at great speed without bending his knees; walking, on the other hand, bored him. He had the immobility of a cat too, and could sit for long stretches without stirring.

Peggy Guggenheim also recalled Holms’s “elastic quality,” adding rather ominously, “Physically, he seemed barely to be knit together. You felt as if he might fall apart anywhere.”

As indeed he did: quietly but totally and irretrievably. The story of this strange debacle – in so far as it can be pieced together from the somewhat meagre sources – will form the subject of my next post.

I very much enjoyed reading this Jonathan, and learning about Holms, who i most certainly have never heard of before. I haven’t googled for a picture yet but I am imagining him to look like the laughing cavalier..

On the subject of your quote by Shelley: “A man cannot say, ‘I will compose poetry’ – Last week I read a rebuttal of sorts, in the foreword of Hubert Selby Jnr’s Last Exit to Brooklyn , where HSJ talks about the fact that he had never held the slightest desire to be a writer, but fresh out of the navy and with no work prospects he thought that being a writer might be a decent way out of poverty so set about learning how to be one. Interestingly different from 99.9% of writers who say that they knew they wanted to be a writer from birth

Worm: Glad you enjoyed this but a word of warning about Googling for images of John Holms — there is, it seems, a porn star of the same name and his claim to fame is amply and repeatedly represented.

You’ve left me on tenterhooks – I look forward to part two! “He could scuttle along on all fours at great speed without bending his knees” – i’ve just tried and failed.

I know I would be richer and more famous if I didn’t suffer from that damned Blogger’s Block.

A fascinating post, Jonathon. It does seem extraordinary that a writer considered by his contemporaries to be so gifted achieved so little of literary note; I assume that the single short story, a few essays and the unfinished poems were all unremarkable. From your account I get the impression of a Ustinov figure, massively erudite, a mimic, an outstanding actor; in present-day terms: a chat show host’s dream. But what of the demons that lurked within? Were they the great inhibitors on an otherwise free-flowing imagination. I really look forward to the second part of the post.

One of the most valuable aspects of The Dabbler is, for me, the promptings to re-visit books and articles once read and now just part of inaccurate memory. The references to Coleridge had me thinking of a frustrated genius, the addiction to opium, the terrible constipation, the great generosity and decency, and, of course, magnificent poetry. The post sent me back to my now dust-laden copy of Richard Holmes’ Coleridge – Early Visions. I wanted to see if the great biographer had offered an explanation for the writing block of October 1800. It may well have been a combination of factors, but the decision by Wordsworth to reject Coleridge’s Christabel for inclusion in the Lyrical Ballads seems to have been a devastating blow. I can only surmise that rejection of the cherished product of a writer’s imagination is a primary cause of writing block.

Terrific stuff Jonathan!

I wonder if even now someone is trying to write Holms’s biography but finding themselves strangely blocked…

Another way of looking at this story is that it is the revenge of the timid, the ugly and the wimpish to be immortalised by their words, while the handsome, domineering giant leaves no trace.

Malcolm Gladwell has his uses. Your fabulously intriguing post reminded me of a piece of his on ‘Late Bloomers’ (link at bottom):

http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2008/10/20/081020fa_fact_gladwell?currentPage=all