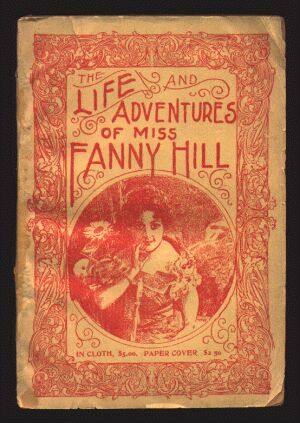

This week Jonathon Green salutes the author of Fanny Hill, a book with a single aim: ‘to write about a whore without using the language that was seen as part of her stock in trade’…

It is my intention to review, perhaps next week, Emily Brand’s new study of the Georgian Bawdyhouse. My failure as yet to read the text should not, were I a professional (let alone a sock-puppet), stand in the way, but I am foolish and feel the need to peruse. Instead I offer as an amuse-bouche a few words on the era’s John Cleland, author in 1748 of Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (generally known as Fanny Hill) and as such perhaps the only writer have created a pornographic book which is completely without obscenity.

Not that there was yet a proper definition of ‘pornography’ (its first use is in 1842) nor yet the sort of ‘obscene publications’ legislation that was passed in 1857 and revised in 1959. That said, the printers of Cleland’s book, which appeared in 1748, were charged with producing an obscene work, and were found guilty. Cleland himself renounced the novel as ‘a Book I disdain to defend, and wish, from my Soul, buried and forgot’ and it was removed from circulation, remaining off-limits until 1966. It was alleged that Cleland was paid off to avoid his writing any more ‘obscenity’ with a government pension of £100 a year for life. If so he must have squandered it: he died poor in 1786.

Such was the future. In 1748 he had a single aim: to write about a whore without using the language that was seen as part of her stock in trade. He does not, of course, escape slang’s inevitable themes. Thus the penis (‘an object of terror and delight’) is variously an axe, a battering ram (with, like all the erections we encounter, a scarlet ‘head’ be it ‘ruby,’ ‘vermilion,’ ‘flaming red’ or whatever), a red-headed champion, a ‘delicious’ stretcher, a ‘stiff, staring’ truncheon, and a ‘terrible’ weapon. It can also be an engine (invariably ’wonderful’, ‘thick,’ or ‘enormous’), a machine (whether ‘unwieldy’ or ‘formidable’), an instrument, a picklock (the labia being ‘soft-oil’d wards’ which it opens) and a wedge. If the penis is a conduit-pipe (and elsewhere a pipe), then the vagina is the pleasure conduit. It can be a staff of love, a sensitive plant (a contradictory image, since the standard version shrinks rather than grows when touched), a wand, a white staff, and, less obviously a fescue (an old term that plays on its standard meaning: ‘a small stick, pin, etc. used for pointing out the letters to children learning to read; a pointer’) one of the wide selection of penis as pointed instrument images. Morsel is also on offer, but doubtless Fanny is only being figurative (in one thing Cleland is faithful to the porn tradition: no-one is ever under-endowed), and the morsel is being ‘engorged’ by her delicate glutton or nether mouth.

Fanny, being a professional, is obliged to be ‘up for it’ but she differs from most of her peers, at least as recorded, in enjoying the sex and having orgasms. But as slang (and pornography), even euphemised, makes sure, the over-riding image is of the submissive female, even slightly reluctant; her honour or at least her body always requiring a degree of force. Thus the vagina is the ready made breach for love’s assaults, the furrow, which ‘he ploughs up’, the saddle (‘He was too firm fix’d in the saddle for me to compass flinging him’). Its physical nature and bodily position are emphasised: the central furrow, the centre of attraction, the ‘soft, narrow chink’, the ‘tender cleft of flesh’, the ‘cloven stamp of female distinction’. It is also a hostess for sexual enjoyment: mount pleasant (used in the plural form for the breasts), the seat of pleasure, the pleasure girth and pleasure pivot. It is a jewel (though lady’s jewels, like the later family ones, are the testicles), the maiden-toy, the main spot or main avenue and the mouth of nature. It is also, and here one may note Cleland’s consciously punning name for his heroine, which might be ‘translated’ as ‘Mount of Venus’, the fanny. All of which imply pleasure and enthusiasm. Only in the use of pit, slit and slash does he present another slang trope: the vagina as wound (and Fanny calls it that too) and threatening, unfathomable abyss. The testicles are the tried and tested balls, not to mention the treasure bag of nature’s sweets. The pubic hair is moss or a thicket.

As for intercourse, one finds fall, as in ‘give her a fall’, and nick and nail, which echo the slang theme of sex as man-to-woman violence . The orgasm is a let-go and to have one is to go or go off. The released semen is an injection (‘His oily balsamic injection mixing deliciously with the sluices in flow from me’). The stallion capable of two consecutive bouts, is ‘loaded for a double-fire.’

Finally the house of conveniency (a house of convenience was merely a privy) where Fanny works. Run by an abbess or mother its employs hackneys (like the hackney horse they are ‘for hire’) and misses of the town and opens its door to cullies (a word that fittingly means a gullible fool as well as a whore’s client).

Whether one dismisses Cleland’s language as over-wrought and at best material for latterday parody or, like the new DNB ‘a stylistic tour de force, employing a dazzling variety of metaphors for parts of the body and for sexual acts,’ its euphemistic role remains undeniable. Though it is hard for what are perhaps the coarser sensibilities of modern life to see quite how anyone derived sexual thrills from his elaborate phraseology and protracted but strangely ‘hands-off’ copulations.

Cleland’s work is ‘literature’ now, but in its day it was scarcely better respected than such pornographic staples as Fifteen Plagues of a Maidenhead or The School for Girls. It was certainly prosecuted with similar vigour and for all his denials, Cleland remained branded with the reputation of his only really major work. The use of euphemisms may also be tied to another aspect of Cleland’s writing, his claim that he only wrote of vice to expose its evils. As Fanny herself puts it ‘If I have painted vice all in its gayest colours, if I have deck’d it with flowers, it has been solely in order to make the worthier, the solemner sacrifice of it, to virtue.’ Like the old News of the World, Cleland ‘made his excuses and left’, but not before telling the story, and embroidering it in euphemistic language that while technically ‘clean’ leaves no doubts as to its intent.

It has always bemused me how Fanny Hill can be seen as a work of ‘literature’ as anyone who has read it will know that it is pretty feeble stuff that gets quite tedious after a few chapters of endless euphemisms. In fact is there any book of straight up erotica that isn’t utterly repetitive and poorly ‘plotted’? Anais Nin perhaps?

Who were the magistrates stroke local squires trying to protect? not the kids surely, they were all up the chimney from the age of five, penis envy more than likely.

Therese Raquin is quite erotic in places, all those naked burds covered in nutty slack, waving their mattocks and sweating, old Zola had quite a fertile imagination.

I remember reading a thing by Alexander Trocchi called Helen and Desire that was a right load of old flannel

Cleland’s endlessly baroque ways of describing the same two or three body parts or physical acts remind me a bit of the variations recorded in Mr Slang’s earlier post on Pierce Egan and the ‘sweet science’ of fisticuffs. Maybe the sports journalist and the pornographer face a similar technical challenge — finding language for a repetitious, physical activity that is perhaps pre- or even anti-linguistic by its nature?

There’s a good piece on Cleland in the current London Review of Books, where Terry Eagleton makes some interesting points of this nature:

Pornography finds it hard to tell a story. Sex is too repetitive a business for that. The sexual repertoire of human beings is severely constrained by the nature of their bodies. Like debates in parliament, it gives rise to endless variations on the same old positions: biology is at odds with narrativity. Anxious for the reproduction of the species, however, Nature has wisely ordained that its repetitiveness should do little to abate our enthusiasm for it. As with the legendary amnesia of the goldfish, we come to it perpetually fresh.

Ditto commentary on middle-distance running, and the great Brendan Foster, who once said, as if reading from a thesaurus “the pace is starting to pick up, it’s starting to accelerate, it’s starting to speed up and it’s starting to move.”

I live not far from the neighborhood of Mount Pleasant, in the northwest quadrant of Washington, DC, which was originally built up and named by rather stuffy folk.

Should slang really come out of books, and an author’s need for new phrasings? I suppose that one can carry this line of thought too far, yet there seems a difference between the slang one gathers in literary works and that one learns in the locker room. Not that expressions don’t flow both ways, but one would like some assurance that they have actually been used, other than by writers. But that sounds like a question for a lexicographer.