We are programmed to trust a dictionary, but should we? Jonathon Green – the leading lexicographer of English slang – advises that dictionaries should carry a lexical health warning…

Lexicography is about demystifying, of cutting out the fanciful crap and aiming for some kind of truth. This is usually done on a local scale: the definitions and etymologies you offer. But there is a bigger picture: the dictionary itself. The mystique of the dictionary. The Universal Authorising Dictionary of ‘Is it in the dictionary?’ ‘I’ll look it up in the dictionary’ ‘It isn’t in the dictionary’. The dictionary? There are dozens at any one time and the reality is that ‘the dictionary’ tends to be the one that resides upon the speaker’s shelf. Or, these days, screen. But if all are equal then some are more equal than others. From 1755 to the emergence in the 1880s of the first fascicles of what would become the Oxford English Dictionary, it was Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language that was the word-book of final appeal. Not for nothing did Thackeray’s Becky Sharp signify her emancipation from the schoolroom by tossing a copy from the coach that bore her away from Miss Pinkerton’s Academy for Young Ladies. The great lexicographer, as Miss P. apostrophised him, stood for linguistic authority. Miss Sharp was unimpressed.

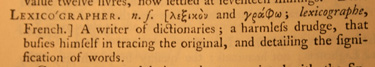

We are programmed to trust the dictionary, but are we sensible? The great lexicographer might equally well have been known as the great fabricator. Johnson’s book is a testament to Johnson’s personality. He was the first ‘modern’ to include quotations illustrative of usage in his lexicon, their task to back up the definitions of a given word. The concept of ‘historical principles’, which is applied to any dictionary that displays such examples, had not yet been coined. But that was what Johnson was doing. However it was Johnson’s history and Johnson’s principles. The writers on whom he drew were only to be those that he saw of the first quality. His citations showed how a word had been used, but even more important, how it had been used properly. If the writer had not quite come up to Johnson’s mark, then the Doctor saw nothing wrong in tweaking the material to fit his requirements. Similarly his definitions: the concept of disinterested defining, a given of modern dictionaries, does not seem to have worried him. The ‘big’ concepts: God, liberty, freedom, power, religion, were laid out in terms to which an Anglican Tory such as Johnson could subscribe. As for less portentous definitions – ‘oats’, ‘lexicographer’ and ‘patron’ remain best known – these were all well and good, but again, a little short on the necessary disinterestedness.

Not all the problems are down to personality. Prevailing cultural standards will have their say. Many of my predecessors found the inclusion of obscenities challenging. Not all slang is ‘dirty’ words but most ‘dirty’ words are listed as slang and they have to be included. And if, like my predecessor Eric Partridge, one professes due respect for the dictionary, such respect can promote absurdities. The 19th century Oxford offered the word shit. Partridge took this as permission and did the same. No blanks required. But the OED passes over slang’s adjacent shit-stirrer or shithead, for instance, and thus for these one finds Partridge preferring sh-t. No point in sneering, but one may surely laugh.

It seems to me that Johnson’s work contains an essential paradox. In attempting to offer a didactic work, setting out definitions that conformed to a specific point of view, he might be seen as attempting to control the language. And in this he was, of course, following the example of the French Academy, whose own dictionary, the product of its members, the ‘Forty Immortals’, had taken sixty years to complete and which, in successive editions remains an exemplar of proscriptiveness. Johnson had taken just nine years to do the job and as his friend David Garrick put it ‘had beat forty French and could beat forty more’. His list of headwords – what goes in and by definition what stays out – reflects his desire to purge the lexis. Yet if one reads his introduction one finds a far more pragmatic figure. When I wrote my history of lexicography, I chose the title ‘Chasing the Sun’, specifically as a tribute to what seemed to me to be Johnson’s open-mindedness. Any attempt to curb the language, he suggested, was the equivalent to the futile efforts of those who climb a mountain in order to entrap the sun, only to find that the sun has moved on to the next peak. And ever more shall do so. This to me seemed the essence of descriptive lexicography, the sensible acknowledgement that language is alive and organic and cannot be pinned down between the covers of a book, however skillfully created.

So my feeling is this: every dictionary should carry some kind of lexical health warning: what you are reading here is incontrovertibly correct and wholly trustworthy – until further research improves upon it. This isn’t theory, it’s fact. I experience it every day. The realities of publication mean that at some stage you have to draw a line under your research and the language isn’t listening. It keeps moving on. Research is potentially infinite and the Internet has hugely multiplied its sources. Range upon range of peaks behind which the unfettered sun, laughing at our feeble efforts at pursuit, dances mockingly ahead. Dig and dig and there’s always the possibility of finding another layer to excavate. Another Troy beneath the last.

Not so long ago a friend published a study of slang. It was filled with theories, a dignity that my marginal, disdained topic usually fails to attract. The theories needed underpinning and my work and that of my peers was liberally quoted to back them up. I cannot speak for them, but I know my own product, and I know that some of his citations – for instance a taxonomy of the terms that make up my database – should not be taken as gospel. Or rather that’s exactly what they should be taken for. A concoction created to persuade. Or in this case to awaken an audience of students who are still young enough to find amusing the enunciation of the odd obscenity within a lecture hall. The broad-brush effect is fine, it’s when the figures get quoted that I start to worry. The devil, as we know, is in the details. In the end I felt that he flattered, and may, although certainly not intentionally, have deceived. But perhaps I worry over-much.

You have been warned.

Taken and abbreviated from Jonathon’s forthcoming Odd Job Man: Confessions of a Lexicographer, to be published in 2013.

Haha love the book title JG! Odd job man indeed

Certainly when it comes to etymology I don’t trust a single thing I read, much as i’d love to believe the whimsical explanations

Excellent book, Chasing the Sun. Highly recommended to all.

Most of us have a prescriptivist lurking inside us, however we may know the difficulties of defending prescription. I seem to have an aversion to “-matics”: I spent about a decade recently waiting for “emblematic” to go away (it has started to), and grinding my teeth at the use of “problematic” to mean “is a problem”.

In the essay “More Genteel than God”, collected in Every Force Evolves a Form Guy Davenport reviews a book on Noah Webster, who had the prescriptivist bug bad, and who was far prissier than Samuel Johnson.

I didn’t include Webster, but of course you’re spot on. He is effectively Johnson’s American mirror image. Where Johnson (whose work Webster loathed) wanted to define the world as an English High Tory, Webster aimed to reflect what he believed should be the values of an independent America, though like Johnson with a strong religious bent, and defined accordingly. This is what I wrote in Chasing the Sun:

Webster’s main concern was ‘to counteract social disruption and re-establish the deferential world order that he believed was disintegrating.’ To misunderstand the true meaning of a word was to pave the way to social disorder. Thus the dictionary takes especial care with such key terms as free, equal, democrat, republican, love and laws. Freedom, other than in subjection to divine laws, was absurd; it is seen as ‘violation of the rules of decorum’ and ‘license’. Equality was out of the question: Webster stood foursquare against universal male suffrage. Like Johnson’s defining of Whig and Tory, Webster equated a Democrat with ‘a person who attempts an undue opposition or influence over government by means of private clubs, secret intrigues or by public popular meetings which are extraneous to the Constitution’. Republicans, on the other hand, were ‘friends of our representative Governments…’ As for love, ‘the love of God is the first duty of man…’ Laws existed simply to ‘enjoin the duties of piety and morality’. Injunctions towards such submissiveness can be found throughout the Dictionary. Duty, as might be presumed, is highly valued: do what you are told and ask no questions might have been Webster’s credo. As for education, it was a concept that in Webster’s world had no relation to learning; education was ‘instruction and discipline’, it would fit the young for their future stations. And while a general education was ‘important’ a religious one was ‘indispensable’. The fear of the Lord, as he often declared, quoting the Book of Common Prayer, was the beginning of wisdom.

Glad someone else reads Guy Davenport. The essays collected in The Geography of the Imagination, Every Force…, and The Hunter Gracchus are some of the few literary essays I return to. There’s a lovely short piece on being wrong, ‘Pergolesi’s Dog’, in Every Force…, which tells us, among other treasurable things, that ‘The New York Review of Books once referred to The Petrarch Papers of Dickens and a nodding proofreader at the TLS once let Margery Allingham create a detective named Albert Camus’.

Reminds me of my days as a junior editorial assistant on one of the big English dictionaries. I had been struggling with some ticklish aspect of a definition — possibly the pron or etymology — and sheepishly told a senior colleague that I’d done my very best but couldn’t swear it was altogether, you know, like 100% correct.

“Correct? It is now came the answer, as my handiwork was put through for keyboarding and incorporation into the august tome.

Looking forward to that book, Jonathon.