In this bulletin from Norbiton, Toby examines the place of teeth in the art of fifteenth century Italy and Northern Europe…

I have come to realise that if I am to make any real progress on my much anticipated, much delayed History of Whistling, I will first have to address the associated history of teeth.

I can do no more here than break a little ground, and think for a moment about teeth in art – specifically, the art of fifteenth century Italy and Northern Europe; for this is a world, seemingly, without teeth. The fifteenth century did not paint teeth, and I am forced to document, and speculatively account for, an absence (with a handful of telling exceptions, which I will come to).

It should be noticed first of all that the absence of teeth is not merely determined by whether mouths are painted open or closed, although there is a statistically significant predominance of closed mouths both in quattrocento and also Flemish art. Open mouths are represented as empty caverns, as though painters had no paradigm on which to draw and teeth were simply not in their repertoire.

How to explain this? In part, of course, it is just a question of the pose and its associated history – who could grin through a sitting? But it is a also matter, clearly, of decorum. The mouth parts are one of the portals to the inside of the body, the warm, clammy and damp interior. When Mikhail Bakhtin, discussing Rabelais and the carnivalesque, locates comedy in the ‘material bodily lower stratum’ – the stomach and digestive tract, the genitalia – he might have added that the mouth, the teeth and tongue, are the outermost precincts of this system. The teeth are an emblem of carnality, and to display them a contravention of decorum.

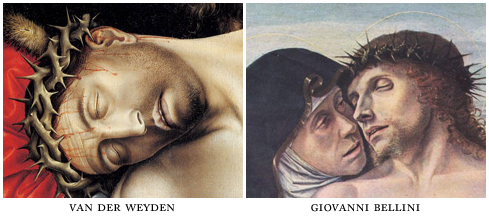

Which brings me to the exceptions. The damned in last judgements, wedded in life to their mortal flesh, have teeth, and they gnash them. So do all manner of animals and devils. So, of course, do skulls, teeth bared in death. And so, not strangely in all these connections, does the dead Christ, in paintings for example by van der Weyden and by Giovanni Bellini.

A dead Christ is an emblem of the fully incarnate god. To look on the face of a dead god is to see him as a man. And if Christ is fully man, then he must have a full set of teeth.

By the sixteenth century the gawping peasants who are finding their way on to panels and canvases also have teeth, plenty of them, wonky and yellow and gapped and hilarious, a trope anticipated by a very few Netherlandish paintings of the fifteenth century, such as the Portinari Altarpiece by Hugo van der Goes which so astonished Florence when it was displayed there in 1483.

And in fact, properly sensitised, if we look back at quattrocento art, we do find examples of painted teeth which do not fit the pattern of rule and exception, as though an arcane painterly language is being spoken which we are only now tuning in to, the subtleties of which we have not yet fully penetrated; as though our thoughts on carnality and death were in fact over-determined, and the concern of painters in fact lay elsewhere.

It comes as something of a shock, then, to switch to something from a more comfortably demotic age and culture, and see teeth painted with unabashed and uncryptic glee, as here by Frans Hals:

But this picture still falls, if my instinct is correct, fully within the accepted visual code of teeth. Bared teeth suggest carnality and death and this piece, like so much Dutch art of the seventeenth century, is about transience considered not as a boon of providence but as a mortal sadness.

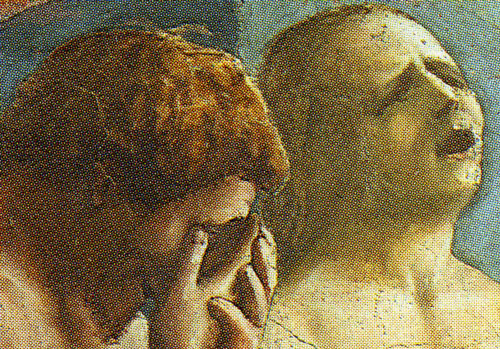

And, to come full circle, it is no more shocking, I think, than this:

This is Masaccio, of course, the great progenitor of the Florentine Renaissance, and these are Adam and Eve expelled from Paradise. In spite of whatever I may have said about the inherited decorum, about the general absence of represented teeth, in this case the absence is almost the focus of the painting; not so much because these individuals are so clearly ill-fitted for the rigours of the world, which is going to demand among other things a strong set of teeth; but rather because the absence of teeth suggests that coming thus abruptly into the mortal state is not a dispossession, but more like the taking possession of a ransacked house; and the only form of protest available is a speechless, voiceless grief.

I had never previously noted the absence of teeth Toby! I think from memory that I’ve seen a few sets of teeth in Hieronymous Bosch pictures, especially in ‘Christ carrying the Cross’

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hieronymus_Bosch_055.jpg

Teeth and all things teeth were a Bosch speciality. Bosch’s devilish creatures have teeth in the same way that, for us, sharks and dinosaurs have teeth. If, as Bruce Chatwin speculates in The Songlines, we spent millions of years as the speciality prey of a toothy beast with whom we shared the caves that were otherwise our refuge, then we might have been programmed to mistrust the flash of canines at quite a profound level.

I’m still holding out for the History of Whistling.

This is almost ridiculously interesting and prompts all kinds of thoughts. In his book A Brief History of the Smile, Angus Trumble observes that for most of art history a proper tooth-baring smile has been reserved for “dirty old men, misers, drunks, whores, gypsies, people undergoing experiences of religious ecstasy, dwarves, lunatics, monsters, ghosts, the possessed, the damned, and—all together now—tax collectors”. In the Renaissance and indeed for long after smiling appears to have been seen not just as a breach of decorum but as a failure of self-possession – an aristocratic virtue that most sitters for portraits would have been quite anxious to communicate. An easy smile was associated not with openness and warmth but with deceit and/or moral weakness (in women, it would be preeminently the sign of the Temptress).

One of the Church Fathers, I think Chrysostom, is supposed to have written that Christ, being the perfect man, never smiled or laughed.

So when and why did all this change? Probably, our idea of the smile as central to facial aesthetics is one that could not have arisen before the advent of modern dentistry. Moving pictures and snap photography must also have something to do with it – suddenly we have informal, unposed images of the fleeting smiles that are the only really attractive kind.

I didn’t know of Angus Trumble’s book – looks very interesting. I love that idea that a smile is a mark of incontinence.

I must say, I hadn’t considered dentistry as a factor, but you must be right.

I had a paragraphy pencilled in on exposure times in photography – I don’t know if you’ve seen these from the end of the nineteenth century – smiling Victorians. The point being that it took the technology some time to catch up with fleeting smiles

http://www.retronaut.co/2010/06/victorians-smiling-1800s/

However, I’m sure that photography allowed the tooth to emerge from its strange representative niche of skulls, devils and horses – and will have no doubt in turn created the cult/iconography of the smile which are heir today, whereby – as Gaw indicates below – people get quite angry if you don’t smile in a photograph.

Your man Trumble no doubt has something to say about this. I’m going to have a look, thanks for the tip

I rather fancy there are no teeth in Degas – check out for example the huge yawn in Two Women Ironing – not a pearly white in sight…

So I see – I bet there’s some painterly knowhow about teeth being less visible than you think in the world, the sort of thing children put in because they know they’re there, rather than because they can actually see them.

going much much further back, isn’t the smile used by animals (dogs, primates) to signal submission? So perhaps there’s some atavistic throw back to the denigration of smiling as a sign of weakness, shiftyness and uncertainty?

I have every sympathy with the medievals, in that I find it difficult to give a big, unselfconscious smile on demand. I feel acutely awkward when I’m asked to put on a grin for the camera. According to my brother, I look as if I’m struggling with a bout of constipation in family photos.

like this G? http://callumreviews.files.wordpress.com/2010/05/brown-smile.jpg

Do you also get strangers telling you to cheer up? I get that occasionally. Cult of the smile. I’d reply that smiling is a sign of weakness and emotional incontinence, but it might come over a touch psychopathic.

Brit reckons I have a ‘slightly lugubrious amiability’. I suppose that would leave strangers guessing.

Milan Kundera has a long and interesting digression on the smile, laughter, photography and all that in one of his novels, but as is often the case with MK the precise details of what seemed very insightful at the time and even which book I read it in completely escape me now.

Brilliant stuff, especially that ‘taking possession of a ransacked house”.

I’m looking forward to you bringing the History of Teeth right up to date with a chapter on Martin Amis.

thanks Brit – but I’m really out of my depth with cosmetic dentistry.

I can only apologise if I inadvertently brought the Amis ‘teeth’ to mind.