Remembering the dead is easy when they’re part of the furniture…

In the room of quattrocento sculpture in the Louvre, lined up with the portrait busts of Filippo Strozzi and Dietisalvi Neroni and the rest, there is an odd relic of Florentine interior design: a terracotta death mask of a woman in a scalloped decorative niche.

It is a rare survival. From a remark by Vasari, it seems that Florentine palazzi were filled with such objects, typically set high-up over doorways, cornices, windows and so on, not unlike the elevated portrait elements on tombs in Florentine churches. You would glance up and see the illustrious dead of the family not only commemorated but virtually present, a significant part of the weight and consequence of a family’s current estate.

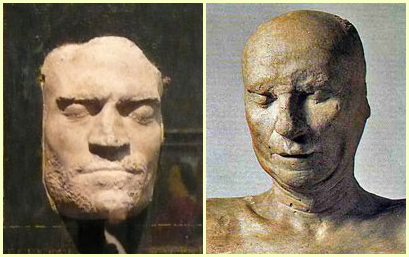

The placement of the Louvre death mask among the portrait busts is not accidental. A death mask is a portrait in extremis, for one thing. The Byzantines, to whom Florence owed much of its artistic heritage, especially revered their acheiropoietic icons – icons which were not the work of human hands but were made, they believed, by miraculous transmission. If death masks, where the transmission was routinely material, were not miraculous, they were nevertheless acheiropoietic; even to us they have something of the photographic about them, a greater fidelity than the intervention of human sensibilities can guarantee, as here for instance, in the famous death masks of Lorenzo de’Medici and Brunelleschi:

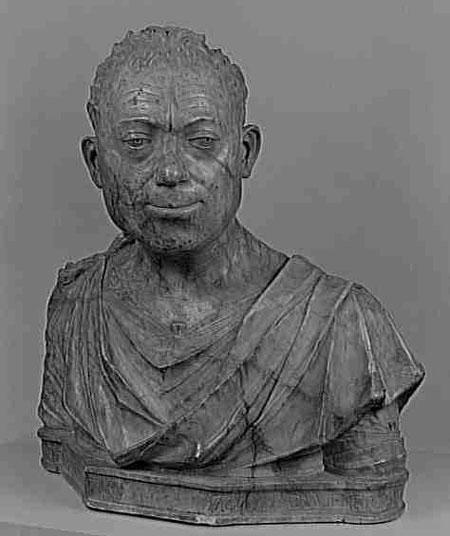

Conversely, Florentine portrait busts, while often done from the life, were frequently also done from the death, so to speak, using death masks as sketches. The death mask is a potential portrait bust in the raw. The Florentine busts, emulating the great Roman busts, are of both male and female subjects; and while the female busts tend to smoother, more generalised ideals of womanhood, the male busts are more markedly individual – as for instance in the bust of the humanist confidante of Cosimo de’Medici, Dietisalvi Neroni:

The more characterful these portrait busts were, in a sense the less realistic they were too – that is, the more marvellous or quasi-miraculous: no longer mere objects of stone, representations of ideals of saints and so on, but real, petrified humans. To fill your house with stone people was to fill it with magical totems.

Not, of course, that the Florentine family would have sensed that oddity: doubtless these masks and busts were only furniture to them, gathering dust above their heads. Or, to put it another way, the dead are part of a family’s furniture.

Nevertheless, Florentine furniture was powerfully constellated. Florentines grandees furnished their houses sparsely – a few tapestries, chests, benches along the walls, and so on – but the objects were always to some degree significant, emblematic. A bride coming into her new home would bring a bed and a chest as part of her trousseau; generation by generation the house would accumulate beds and chests from various marriages, each no doubt at some level remembered. Similarly each birth in the house would be celebrated with a so-called desco da parto, a birth tondo which could be of moulded terracotta, of precious metal, or a painted board. And so on.

Once again, it is worth stressing the commonplace nature of these furnishings. No one walks around their house like a magus through the universe. But there are analogies with our own experience. Belongings express power and wealth but also the facts of ancestry – for instance my children are growing up eating their dinner off a wobbly table under which family members sheltered during the Blitz, and are occasionally reminded of this, to their exquisite boredom. And while we may not commission death masks of our parents any more, we do keep photographs of the dead at hand, as though, brought out from time to time, they might attest to a brief penumbra of afterlife, and ward off our own long night of forgetfulness.

A lovely post, Toby.

Thanks Nige

I love the bust of Dietisalvi Neroni – such character, you can almost hear him speaking away in italian

Yes, except he’s wearing a toga – epitome of Republican Virtue – so Latin, perhaps.

He was exiled a couple of years after the bust was done, accused of plotting against Piero de’Medici.