A break in Paris provides Toby Ferris an opportunity to consider how we overcome our everyday exhaustion.

Last week I was in Paris, and successfully carried out a minor mission in the Louvre to locate the solitary Bruegel they have hanging there, known as the Mendicants or Beggars. It is a very small canvas, and a late one, and hangs in a room of its own alongside a handful of contemporary drawings.

The mendicants are depicted on the day known as Copper Monday, a day of procession and almsgiving which followed Epiphany, as we know from their traditional paper crowns; they are also wearing the foxtails and (in one case) the bells associated with leprosy, the disease which accounts for their identikit disability. They are accompanied by a woman with a begging bowl who is collecting on their behalf while they perform – because it is a performance, however grotesque: the hats, the foxtails, the sense of festival and carnival.

It is of course not untypical of Bruegel to document the inhabitants of society’s margins, and not necessarily with sympathy – his concern is typically intellectual, observational, curious; and the organisation of his material tends to the emblematic and proverbial. The mendicant figures are thus only in part a reflection of our own inhumanity, you feel; they are also a source of horror.

But there is in these figures nonetheless a battling physical energy which, if not exactly heroic, is certainly notable. In particular, the figure on the left in the red hat, and the figure to his right, have managed to grapple themselves to the upright with, if not grace, then vigour and determination.

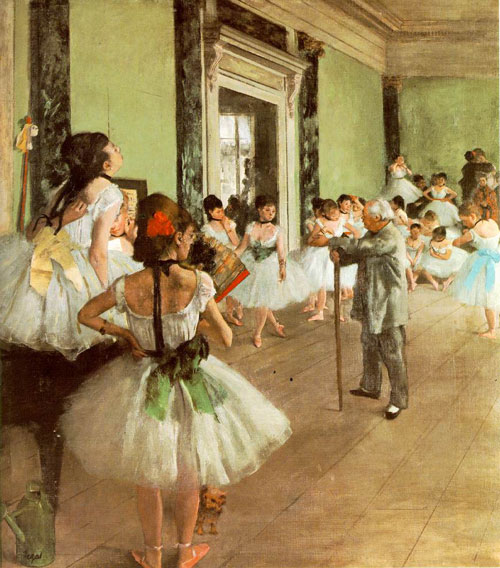

A similar dynamic is illustrated in another painting I saw while in Paris – La classe de danse (1873-6) by Degas:

Degas’s dancers, when they are not caught in movement, are famously earthbound – ungainly girls on tired feet, scratching, yawning, stretching. At the centre of this particular group is the dancing master, planted solidly on three feet, as it were, the paradoxical source, in his stillness and control, of the latent energy in the room. When these dancers spring to action the alteration is instantaneous and complete: from rest to movement is not a continuum, you feel, but a sudden jerky galvanic resistance to the entropic collapse of the universe.

I remember that George Eliot talked somewhere or other (in her letters? in an essay? perhaps in one of the novels) about tiredness, listlessness; about how, in order to do anything, you have to build and maintain a mental bridge of energy over the abyss of physical and intellectual tiredness.

I don’t know about a bridge of energy – it sounds exhausting before you even start – but that sense of conscious focus in performance unites Bruegel’s beggars and Degas’s dancers. It is something we all do, perhaps especially as we age – drag ourselves up by our bootstraps, up to the vertical, on a more or less daily basis. We drape our necessary roles over a concealed (or ill-concealed) core of ennui, of exhaustion.

On the way to the Musee d’Orsay I happened to pass man begging in the street. He was in late middle age, heavy-built with a prophet’s beard. He was propelling himself along in a sort of agony of balance and endurance, with a pair of crutches stuck under his armpits, dragging the insides of his splayed feet on the pavement behind him. He was wearing discoloured white trainers which almost smoked with the friction. I do not know how he did not pitch forward on his face with each thump of the crutches.

It was, if I can be forgiven for thinking it, an impressive performance.

“He was propelling himself along in a sort of agony of balance and endurance, with a pair of crutches stuck under his armpits, dragging the insides of his splayed feet on the pavement behind him.”

I think you saw a character from a Samuel Beckett story.

Ah, an absinthe-induced literary figment, you mean? Hadn’t considered that. It was Paris, I suppose. Or then again, perhaps it was him who had been reading Beckett.

It was a relief to read this, confirming as it does that it’s normal for life to be really very tiring.

To cite the wisdom of another sage, Nigella Lawson reckons it’s only humanly possible to do two out of the following three things properly: work, kids, social life. True.

what is this so called ‘social life’ you speak of??

“We drape our necessary roles over a concealed (or ill-concealed) core of ennui, of exhaustion.”

Pretty ill-concealed this morning I’d say. In fact my “mental bridge of energy” is generally more of a pier or jetty …