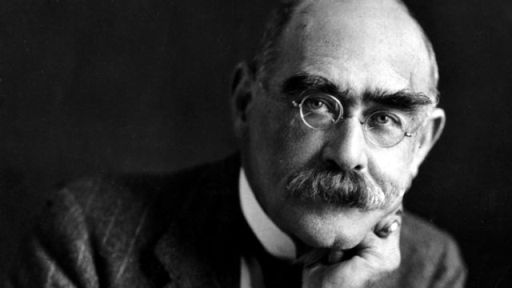

His soldier Tommy is one of the great English archetypes. But did Kipling invent or merely popularise him? Mr Slang investigates…

Kipling, by allusion, has cropped up regularly in these posts. Enough of the oily rags. It is time for the engineer.

Yet Kipling is not at first sight a particularly ‘slangy’ author. In his children’s tale ‘How the First Letter Was Written’ he (as Tegumai) admonishes Taffy (his daughter Josephine) for using ‘awful’ to mean ‘great’. ‘Taffy,’ said Tegumai, ‘how often have I told you not to use slang? “Awful” isn’t a pretty word.”.’ Nor, really, was it slang, and Kipling may have preached but he did not practice. There are hundreds of slang words and phrases in the works, as well as a wide range of job-specific jargon, typically in his sea stories. He uses it for the most basic of reasons: to confer authenticity. He is not a coiner, but a recorder, and his slang lexis is that of the contemporary world, leavened, as in the conversations of the Soldiers Three, by the specifics of a given background. He claimed himself to be implacable in his choice of terms: ‘I will write what I please. I will not alter a line. If it pleases me to do so I will refer to Her Gracious majesty – bless her! – as the little fat widow of Windsor and fill the mouth of Mulvaney with filth and oaths.’ But there were limits. He suggests that ‘Thomas [i.e. Tommy Atkins] really ought to be supplied with a new Adjective to help him express his opinions’ but we never read it and see only blanks. (Judging by the evidence of Frederick Manning’s Her Privates We and other World War I memoirs one may assume it was ‘fucking’ — ‘bloody’ being claimed by Australia). He was also happy to accommodate his audiences. The language of stories originally written in India, where his readers would have had a good smattering of what a newly published new dictionary of Anglo-Indian imperial pidgin termed ‘Hobson-Jobson’ , had to be simplified for those ‘at home’. Though such changes are not mandatory and Soldiers Three – where it would have been foolish and anomalous to put standard English into the mouths of men who rarely speak it – is full of pidgin, e.g. jildi, mafeesh, dekko, chee-chee, pukka, peg and baksheesh.

It was Kipling’s use of English that drew most comment. ‘Among Mr. Kipling’s discoveries of new kinds of characters,’ said his fan, the poet and critic Andrew Lang, ‘probably the most popular is his invention of the British soldier in India.’ Kipling was less grateful than Lang might have expected. A letter of 1890 states how ‘the long-haired literati of the Savile Club are swearing that I “invented” my soldier talk in Soldiers Three. Seeing that not one of these critters has been within earshot of a barrack, I am naturally wrath.’ Kipling had not invented it. He had picked it up, along with the prototypes of his characters in such oases of ex-patriate tedium as the barracks at Mian Mar where as a journalist he had enjoyed relatively privileged access.

The ‘soldier talk’, his creation or otherwise, came to exemplify a type. As Mafia dons and ‘soldiers’ apparently began modelling themselves on The Godfather trilogy, so did the British trooper take on Kipling’s fictions as exemplars. The former subaltern Sir George Younghusband recalled in A Soldier’s Memories (1917), ‘I myself had served for many years with soldiers, but had never heard the words or expressions that Rudyard Kipling’s soldiers used […] But sure enough, a few years after, the soldiers thought, and talked, and expressed themselves exactly like Rudyard Kipling had taught them in his stories […] Kipling made the modern soldier.’ Perhaps. Rigorous checking will find much of the language already available. But kudos goes to the populariser.

Whether, as the academic P.J. Keating claims, Kipling’s rendition of Tommy Atkins (a nickname he had not invented but popularised as never before) also made ‘a complete break with convention and provides English fiction with a new cockney archetype’ is debatable. Kipling, as noted, was a recorder, his slang terms are there for character delineation. He is not, Raj-isms aside, displaying much in the way of counter-linguistic neologism. In his one excursion to the East End, ‘The Record of Badalia Herodsfoot’ (1893) there is slang, as there needs to be, but it is unexceptional.

Of the Soldiers Three one is Irish, and something of a stage Irishman too, one from Yorkshire, and thus dialectal, and Ortheris, the Cockney, is relatively quiet, or at least as compared with the loquacious Mulvaney, on whom the burden of tale-telling rests. His vocabulary is far smaller and far more mundane than is that of the self-consciously worldly ’Arry, but his background is much poorer, while ’Arry is more lower-middle than truly working-class.

Kipling’s most prolific use of slang came in the quasi-biographical school stories that appeared in Stalky and Co (1899) and various subsequent collections. The context here, since the school existed to prepare boys for the army, was also military, though ‘Stalky’ and ‘M’Turk’ are soldiers only in embryo, while ‘Beetle’, i.e. Kipling, is destined only for literary campaigning.

Much of the slang is in general use, but many terms are not that far from Billy Bunter who although he would not appear in print until 1908, had been invented by ‘Frank Richards’ in an unpublished story of the 1890s. They include: ass and ass about (the animal, rather than the posterior), my aunt!, bags I!, bait (a rage), like beans (energetically), biznai, bother!, blow!, blub (to cry), brew (a study feast), bug-hunter (an entomologist), burble, bust-up (a row), buzz (to throw), cat (to vomit), cave! (look out!) and keep cave, cram (a tutor or last-minute pre-examination work), crammer, cribber (one who uses some form of illicit aid when taking examinations), dicker (a dictionary), the suffix –eroo, funk (a coward), golly!, gummy!, impot (an imposition, i.e. punishment of ‘lines’), jammy (easy), jaw (a lecture), padre (a chaplain), pi-jaw (an earnest, moralizing lecture), ripping!, rot (to talk nonsense), scrag (to beat up), slack (lazy), sneak (to tell tales), stinker (a hard piece of work), suck up, swot as noun or verb, tip (of a parent to pass over money), whiff (to smell unpleasantly), whopper, whopping and wigging (a telling-off). Kipling was not a pioneer of school stories – although here, as in his soldier tales, he had a new and more realistic take on the language: such slang as Tom Brown and his chums use is almost wholly adult – but it is hard to believe that many of his successors in the field had not read Stalky.

Fascinating, Jonathon. Do the characters in Soldiers Three demonstrate Kipling’s far greater ease with the use of dialect than slang? Surely Ortheris presented a golden opportunity for Kipling to demonstrate his grasp of wonderfully rich cockney slang, but did he, through this relatively taciturn character, purposely sidestep the challenge?

Nineteenth century Afghanistan:

http://www.kipling.org.uk/poems_youngbrit.htm

And a modern take on it:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1204317/British-soldier-writes-Rudyard-Kipling-poem-damning-attack-conditions.html

Ahh the joys of ‘cave’. Probably the most uttered word at my prep school after ‘quiz’ and ‘ego’

That’s a very interesting complaint about “the long-haired literati of the Savile Club are swearing that I “invented” my soldier talk in Soldiers Three. Seeing that not one of these critters has been within earshot of a barrack, I am naturally wrath.”

Today it would be ‘Guardianistas’…