From dark tourism to Dixieland jazz, Jonathon takes us on a trip to the slang’s heart of darkness…

About ten years ago I went to Auschwitz. This was Auschwitz II, with its iconic ex-Austrian barracks and the that final run of railway tracks, connecting backwards, for this was among the reasons why the camp site was chosen, to lines running in every direction across Europe. I was lucky, if so optimistic a word can be used. It was late in the day, I seemed to be alone. I walked up the track, branching off into the places one goes and at which one looks and they had the effect they are meant to have. I went away and continued my rationale, lecturing on slang, one may laugh now, to audiences of Polish EFL teachers. I went back to London.

What I did not know, perhaps because the term had yet to be coined, or at least not publicized beyond academe, was that this, my death camp trip, came under the rubric of dark tourism. Late as ever, paradoxically so for one so tediously punctual to appointments, I only met dark tourism last week. With its synonyms black tourism and grief tourism and for the classically minded thanatourism, it consists of visiting places associated with violent death. The cartography of human vileness and despair. The map of humanity stripped of pretention. But then I’m a pessimist.

Which adjectival use takes me, of course, to slang’s applications of dark. The standard word comes via old English deorc and there is, the OED tells us, no corresponding adjective in any other Germanic language. However there exists the Old High (that is south-western or southern) German tarchanjan , tarhnen and terchinen which mean to conceal or hide and suggest some kind of shared stem. Latin offers niger, with all that that will bring in the future, and obscurus, opacus, creper, tenebrosus, suffuscus and auster, all of which will be adopted but which in their translation and development will be far less focused; we shall return to dark.

Darkness suggests absence of light, literal and otherwise. The suffix –mans indicated a state of being or a thing and in 16th century cant darkmans was the night and the darkmans budge a villain’s assistant who at dead of night climbs into a house through a window and opens a door to admit the rest of the gang. (A budge was a sneak-thief specializing in furs: standard budge meant lamb’s skin with the wool dressed outwards, maybe from budge, provisions or Old French bochet, a kid. Oliver Twist was an involuntary descendant but Sykes called him a little snakesman.) The night has been dark as Newgate, as an abo’s arsehole, as a nigger’s pocket, the inside of a cow and a yard down a bear’s throat. It can also be the darks and the darkey; West Indian darkers are dark glasses, to be dark is to be near-blind and a darkie a beggar who pretended to be so.

Darkmans (plus dark, dark glim and darkie) can be a ‘dark’, i.e. shuttered, lantern. Sleuths use them but so too do criminals. A dark lanthorn, as well as being synonymous, was one who takes and transmits bribes offered to their master. The 17th century’s dark engineer (from engineer, to manipulate, to perform) was any villain. The dark cully, criminal only for moralists, keeps a mistress and only dares visit her surreptitiously at night. To dark was to knock out or kill as is darken someone’s daylights as is the more recent dark out.

Crime first, prison next. The dark was a solitary confinement cell, it has been modified to dark cell but the menace remains implicit. A dark house or room was for the confinement of the mad (though the former also meant a tavern that offered beds). The OED suggests that to keep someone in the dark is thus rooted. Dark has meant a fool and as an adjective, stupid. To dark it is to say nothing.

There is, since there always is, rhyming slang. After-dark, a (bookmaker’s) clerk, light and dark, a park, dark felt, a belt and dark and dim which works both as noun and verb and means swim.

Ultimately it is all colour. Some is quite neutral: an order of black coffee is in the dark (or with the light out); in Australia dark can be a home-distilled and very strong brandy or a similarly dark tobacco as issued in prisons; as darkie it can also be the nickname for those with dark hair or complexion.

The rest is not. Darkie. Darkey. My first four recorded cites are American (1775 et seq.), the fourth Australian. It doesn’t seem to have caught on in the UK till the 1840s and even then seems scattered. As darkies it had a non-racist use in 19th century London: as a collective term for a variety of late-night music-halls and bars on or near the Strand, usually below ground level, e.g. the Shades, the Cider Cellars and the Coal Hole. Darkie can be found as an adjective or adverb, both derogatory. A darkie-driver semi-euphemizes nigger-driver. In Australia, at least originally, to choke a darkie means to defecate; thus is done through the dark hole, the anus, although that also, at least for misogynists, denotes the vagina. A black woman considered simply for sex is dark meat (plus dark shanks, dark-skinned meat and dark stuff) which can also mean her vagina and, irrespective of skin tone, a brunette.

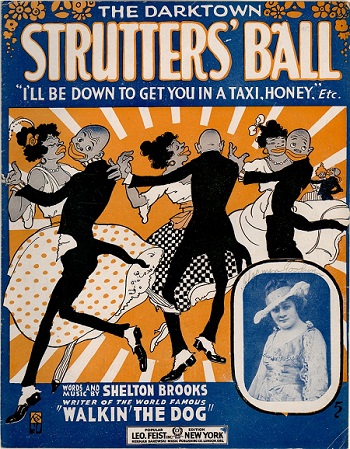

Darktown or darkytown was the black area of a town or city; in 1917 the Original Dixieland Jazz Band recorded ‘The Darktown Strutters Ball’ which jazz standard, popularity over-riding etymology, was inducted into Grammy Hall of Fame in 2006. Pre-independence Johannesburg termed the nearby township of Alexandra Dark City; Australia has used dark man and dark cloud for a Native Australian. Finally, in the complex hierarchy of terms that indicates the precise racial components of a Caribbean skin, dark-sambo indicates a person of mixed race, with one-quarter white to three-quarters black. Sambo, first recorded in Barbados in 1647, comes from Spanish zambo. It too originally describes those of mixed black and Indian or European blood. The literal meaning is yellow monkey.

Fascinating Jonathon, There’s so much to learn from your posts every week

I certainly use ‘dark!’ regularly to appraise sick jokes that my friends tell me

Thanetourism- visiting Margate

Technology has given us “darknets” (private networks), “dark fiber” (unused fiber), and “go dark” (stop transmitting). Physics has dark matter, but that’s jargon, not slang.

Star Wars gave us “the dark side”, originally of “The Force”, but now more widely applied.

Well thank goodness we’re not in the dark about all that… When I was a child, referring to someone as ‘black’ was considered distasteful. But one of my favourite stories from those days was Little Black Sambo. It’s actually a lovely story. Why was it banned?

As for dark tourism, several museums dedicated to failure and loss have opened in recent years.

Oops, misread ‘abo’ – thought it said ‘asbo’ – a euphemism subliminally planted by Martin Amis?

I agree; Little Black Sambo has no taint of racism. It’s totally within a black world, doesn’t sneer at anyone for being black, and has very good tigers (and butter). ‘Sambo’, nonetheless, is of itself a very unpleasant term.

There is possibly a (very small) discussion of what it was acceptable to call non-white people at any given period. In the 60s ‘black’ was definitely the word of choice (as in ‘Power’ and ‘Is Beautiful’.) Prior to that ‘negro’ had been perfectly acceptable. Now it seems to veer between (in the States where such things are more regularly pondered) as veering between ‘Person of Color’ and ‘African-American’ (in parallel with all the other -hyphenates).

If, of course, you want to get among the serious cultural ironies, one of the most famous 19th century ‘minstrels’, white entertainers who blacked up, strummed the banjo and sang songs supposedly of black origin, was William Henry Lane who performed as ‘Juba’ and was seen and written up enthusiastically by a visiting Charles Dickens. ‘Juba’ was himself black, but he too donned the makeup.