Stephen Clarke is the author of A Year in the Merde and numerous other books which take an irreverent look at the French and at Anglo-Gallic relations. In this exclusive post for The Dabbler, originally published in February 2011, he explains why Les Rosbifs have been irritating their continental neighbours for a millennium…

1000 Years of Annoying the French – it sounds a fun way of passing the time, even if, like me, you’re a Francophile. I’ve lived in Paris for 17 years now, and I still get equal enjoyment out of being here and out of teasing my hosts. I feel as though I’m carrying on a great tradition, although of course I do my annoying with jokes rather than arrows and cannons.

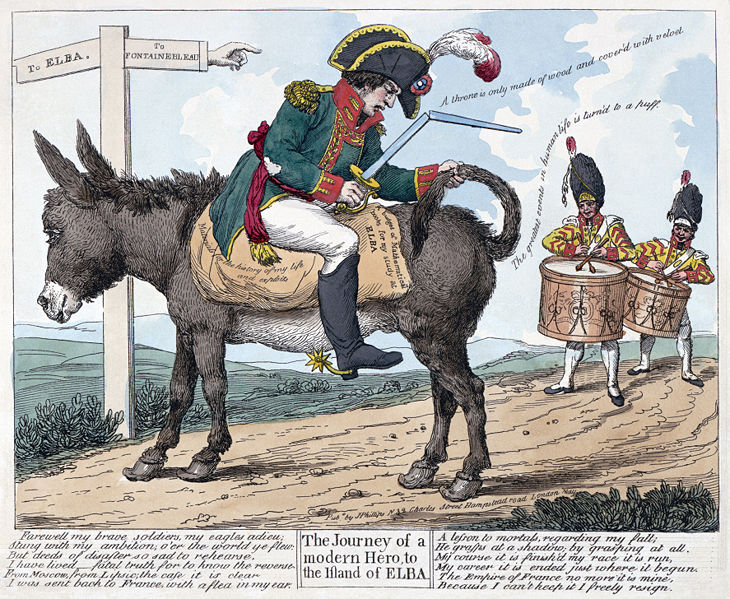

I chose 1000 Years of Annoying the French as the title of my history book as a kind of apology. Looking back, it really did feel as though we had been the aggressors most of the time. And even when Napoleon had a go at getting his own back, we managed to annoy him, not only by sinking his fleet, but also by publishing captured letters in which he was simpering to Josephine about an affair she was having with a butch cavalryman. In short, over the past millennium or more, we’ve never missed a trick.

And the French won’t let us forget it. As a Brit living in France, I am often made to feel personally responsible for, say, the martyrdom of Joan of Arc (“the only thing you Brits ever cooked properly, and even then you burnt her”) and the “murder” of Napoleon – we poisoned his wallpaper, apparently. A surefire plan. As everyone knows, deposed leaders always lick their wall coverings.

But looking into the stories, I was delighted to find that the French actually bear much of the blame for almost all this supposedly Anglo-Saxon mischief.

Take the little-known story of Charles II’s time in Paris, for instance. When Cromwell had Charles I’s head cut off, the teenage heir to the throne took refuge at the Louvre – his mum was a member of the French royal family. But life in Paris wasn’t all it was cracked up to be. France wasn’t sure which way the English revolution would go, so they didn’t want to be too chummy with Charlie, who was kept waiting about in anterooms instead of getting an audience with King Louis XIV. He amused himself by having affairs with marquises, but felt insulted, and saw a chance to get his own back when relations eventually improved and everyone decided he ought to marry a French Princess. Claiming that he couldn’t speak French, he tortured the poor girl by accompanying her to functions and sitting there in total silence, occasionally sneaking off to chat up a mademoiselle in obviously excellent French. He drove his mother and Louis’ family to distraction until it was safe to go back home and grab his dad’s throne. It’s a wonderful story of hormone-fuelled teenage rebellion.

Everywhere I turned in French history, it was a similar story. Anecdotes came to light, myths went belly up. The guillotine, I found, wasn’t a French invention at all – it seems to have been inspired by an ancient gibbet in Halifax, Yorkshire, and in fact, the last thing Docteur Guillotin wanted was to give his name to a killing machine.

Champagne, I proved, wouldn’t be bubbly at all were it not for the intervention of a Brit called Christopher Merret. I wrote to Moët et Chandon, suggesting that they bring out a Merret cuvée alongside their Dom Pérignon brand (Dom P is the French monk wrongly credited with the creation of modern, fizzy Champagne), but of course they ignored me. I didn’t mind – I did it mainly because it allowed me to commit an awful pun – I said “Merret le mérite” (he deserves it). In France, a pun is a valid excuse for doing almost anything.

My favourite story of them all, though, and the one that annoys the modern French the most, is D-Day. I love to ask them if they know how many Frenchmen landed on the beaches of Normandy. Every year, they trot out General de Gaulle’s speech declaring that France “liberated itself”, which is a bit like saying Carla Bruni cuts her own hair, makes all her own clothes and takes photos of herself with her mobile phone. What you see in the magazines is the result of rather a lot of uncredited help.

When I put the key question to French people they usually get it horrendously wrong – and for a good reason. Because the number of French troops in that D-Day force of some 150,000 soldiers was … wait for it … 177. Not 177 divisions or even platoons, but less than 200 men. A mere bootlace in the wave of khaki uniforms emerging from the landing craft, mainly thanks to le Général who didn’t want his men helping les Anglo-Saxons to “colonize” his country.

All of which explains why I got so much pleasure out of writing 1000 Years of Annoying the French – the book is carrying on a noble, millennium-old, tradition of stirring up trouble. In a spirit of cordial friendship, of course.