What a drunken satyr, a grotesquely inflated armadillo and a parachuting nonagenarian have to tell us about not just our death, but everyone’s…

Wisdom is proverbially reticent. The wise need to be eked from their crabby shells; we are, perhaps rightly, suspicious of philosophical or rhetorical fluency.

In a story related in Plutarch’s Letter to Apollonius, Silenus, the improbably wise tutor of Dionysus, is captured by shepherds in the employ of King Midas, and under coercion of one sort or another is made to reveal the singularity, so to speak, at the heart of his wisdom: the greatest blessing available to human beings, he says, is never to have been born; once you have been born, the next greatest blessing is an early death.

This pessimistic line is familiar enough – it appears, for instance, in Oedipus at Colonus – to have become something of a commonplace, but there is a peculiar flavour to it placed in the mouth of Silenus.

Silenus was a species of green man akin to a satyr. In the earliest depictions of him he had cloven hooves, and the legs of a goat or a horse, and while by his classical heyday he was all humanoid, he was invariably accompanied and supported in his teetering drunkenness by satyrs, or balanced precariously on the back of an ass.

His words to Midas are not the dismissive wisdom of an immortal addressing a mortal: they are a confession: this is a superficially carefree being who understands that he himself is destined to extinction. Dionysus and Silenus and the satyrs and their ilk are all gone. And we – mortal hominids – are still very much here.

Extinction and personal death are the pounds and pence of mortality – a common divisible currency which nevertheless occupy distinct mental planes, have different psychic uses. Every individual of every species will die, but some species are more successful than others – more adaptable, more diffused, of greater tenacity or longevity.

All, however, are doomed. We have not only banished the immortals; we have eliminated immortality. We have made a cult of wholesale extinction. We no longer garland sacrificial cows for the honour of the gods, but we erect temples to extinct beings.

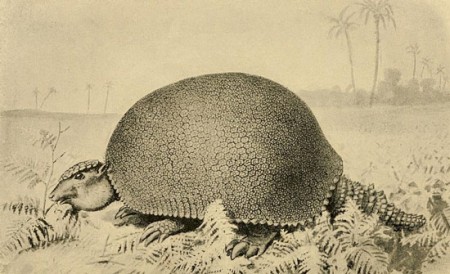

In Berlin, for instance, in the Natural History Museum, there is there fossil of a glyptodon, prised from its shell, a Marsyas of philosophical elucidation.

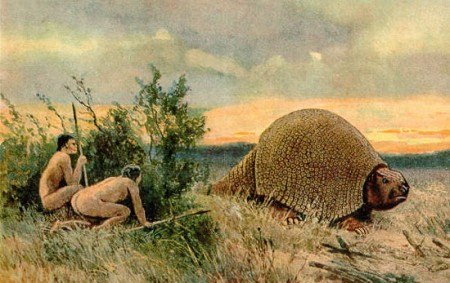

The glyptodon was one of the supersized mammals of the Pleistocene, a grotesquely inflated armadillo, a bumbling conspicuous oddity standing, in the great Venn diagram of the imaginarium, closer to giants, cyclopes, satyrs and gods than to any actual creature. This shambling and pitiful old philosopher was hunted to extinction at the end of the last ice age, by more efficiently evolved and nimble-tooled mammals.

What does the Glyptodon tell us, now that we have captured him, and flayed him, and put him to the test? He tells us that in the grand scale of things we are interesting not for our quiddity but for our generalised qualities; not for our spiritual innerness, but for our material residue. We are interesting as a species, not as individuals. Our survival, insofar as it is likely, will only be in unpredictable fossil form.

What Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy called ‘the terrible wisdom of Silenus’ does not really ring true for us anymore; we could imagine people saying it or thinking it or even believing it, but they would be marginal people, out of the swim – malcontents and misanthropes and cynics. We are currently assured, by contrast, of the possibility of personal fulfilment. You can have a fulfilling life in spite of your always imminent death. Life, it is frequently affirmed, is what you make of it. And thus the highest philosophical embodiment of our essentially comedic age is the parachuting nonagenarian.

But inevitably we have replaced Silenus’s bleak insight with a different, equally bitter one, one that lies, necessarily, in the blind-spot of these near-sighted virtues. Silenus gave himself over to the cultivation of a certain gusto, and the glyptodon and his ilk are interesting; but these serve only to conceal the bald fact that we no longer have even the comfort of a nameable Yorick’s skull awaiting us, but rather, at best, a hazy continuum of papery artist’s impressions.

Deep waters indeed, especially on a bleak Tuesday afternoon.

The first bit of Silenus’ wisdom – the greatest blessing available to human beings, he says, is never to have been born – is, literally, meaningless. The second bit – an early death – takes a bit more arguing. How early is early? Prior to the consciousness of one’s own mortality?

True – or, by another token, there are countless lucky unborns hovering round us like irrational numbers (or like fish, if my memory of Richard Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schatten is accurate).

As for the second, I think the sooner the better is what is implied.

Not saying I agree, of course.

On anti-natalism and a Thomas Hardy poem (“To An Unborn Pauper Child”) see Mark Richardson’s “Must come and bide . . .” blog posting:

http://eraofcasualfridays.net/2012/05/13/must-come-and-bide/

“Had I the ear of wombèd souls

Ere their terrestrial chart unrolls,

And thou wert free

To cease, or be,

Then would I tell thee all I know,

And put it to thee: Wilt thou take Life so?”

Thanks for the link, very interesting – the Benatar in particular looks like a piquant read (“The central idea of this book is that coming into existence is always a serious harm…. most people, under the influence of powerful biological dispositions towards optimism, find this conclusion intolerable.”)

There’s something about this weeks epistle that puts me in mind of Larkin’s Arundel Tomb

Another word from Thomas Hardy bearing on the matter. From his 1902 volume “Poems of the Past and Present”:

BY THE EARTH’S CORPSE

I

“O Lord, why grievest Thou?—

Since Life has ceased to be

Upon this globe, now cold

As lunar land and sea,

And humankind, and fowl, and fur

Are gone eternally,

All is the same to Thee as ere

They knew mortality.”

II

“O Time,” replied the Lord,

“Thou readest me ill, I ween;

Were all the same, I should not grieve

At that late earthly scene,

Now blestly past—though planned by me

With interest close and keen!—

Nay, nay: things now are not the same

As they have earlier been.

III

“Written indelibly

On my eternal mind

Are all the wrongs endured

By Earth’s poor patient kind,

Which my too oft unconscious hand

Let enter undesigned.

No god can cancel deeds foredone,

Or thy old coils unwind!

IV

“As when, in Noë’s days,

I whelmed the plains with sea,

So at this last, when flesh

And herb but fossils be,

And, all extinct, their piteous dust

Revolves obliviously,

That I made Earth, and life, and man,

It still repenteth me!”

Who knew there was so much poetry in long extinct megafauna!?