This week the domestic world is turned inside out as we go looking for wild things in forest rooms.

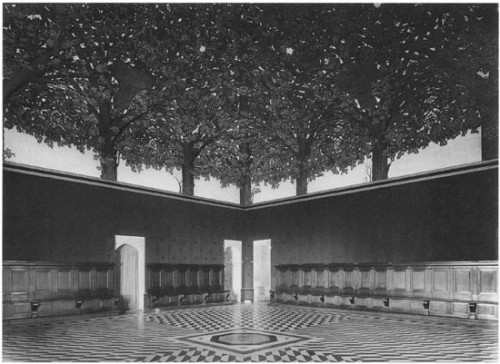

In 1498, at the insistent request of his patron, Duke Ludovico Sforza, Leonardo da Vinci decorated the vault and ceiling of a room of the Castello Sforzesco in Milan with a grove of painted mulberry trees, their branches intertwined in intricate and symmetrical knots, turning a private and interior space into the semblance of an exterior one.

Ours are fairly modern times, and we like to think of building and non-building as distinct categories. We return stray wildlife to the outside (wasps, small birds, flies if they’re lucky), and potter around with draught excluder and sealants, and set up systems of quarantine (doormats, porches, terraces) to manage the transition from one to the other. Buildings are buildings and they are made of brick and glass and other impervious materials. The outside is made of everything else, and has a mind of its own.

The renaissance eye, by contrast, was quick to see the tree in the column. This sensibility had both a classical and a gothic pedigree. Vitruvius, from whom the Renaissance got its architectural theory, had satisfied his need for an originary foundation by interpreting the columns and entablature of classical architecture as a sort of petrified primitive carpentry. Gothic masons, too, had been quick to read natural forms into columns and capitals; their cathedrals and churches sprout carved vegetation, foliage and green men with prolific ease.

It was in this context that Leonardo da Vinci was able to conceive his forest room. However, while the geometry of the trees and the spread of the canopy respect the underlying architecture, they do not elucidate it. To stand in the room is experience disorientation. It is, in spite of all reason, hard to read the room as a room, with a regular architectural scheme. The illusion of paint overpowers the actuality of plaster and panelling.

The only intimation of intellectual clarity lies, paradoxically, in the weave of the branches and the knotting of the gold thread which interlaces them.

The scheme plays on contemporary taste for a design known as the fantasia dei vinci, originally developed for the Este family and imported to Milan by Beatrice d’Este, wife of Ludovico Sforza, who wore it as a filigree thread in her court dress.

The double play on ‘vinci’ (punning on vinci, osiers, as used in wickerwork, and vince, she conquers) was taken up by Leonardo, in part because of the additional play on his own name, but in part also because of his obsession with the construction of knots and knot devices. Knots were geometrical entities which not only represented but informed the created world; they were neither independent of matter (something is always knotted) nor wholly dependent on it (matter – for instance a piece of gold thread – can pass through a knot without altering the identity of the knot). The cosmos itself, it might be said, was an elaborate knotting together of chaos.

In any case, the whole room – knots, symmetry, forest – is clearly an impresa or signifying device, the meaning of which has been linked with the union of the houses of Sforza and Este in marriage, and the dissolution of that union in the death of Beatrice d’Este in childbirth in 1497, an event which seems to have precipitated the decoration of the suite of rooms.

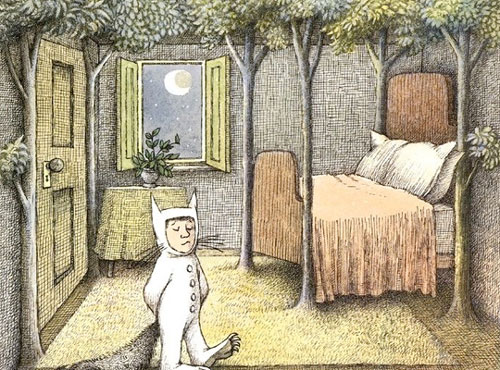

Forests are associated with loss of identity and with spiritual crisis. You go to the forest – Forest of Arden or selva oscura – to lose yourself or find yourself. The forest is where the wild things are, and you are the wild thing in question.

Who knows whether the old Duke in his grief (which seems to have been real enough) bounced off the walls of the Sala delle Asse, or its near neighbour, the Black Room? I suppose it is doubtful. This was a court, after all, not a Bluebeard’s castle, and there were public forms for grieving.

A court in the Quattrocento was a particularly fluid play of interiors and exteriors: private grief is given public form; public treaty are made a family matter; your levée is attended by near-strangers, matters of state are the business of the prince’s private conscience, and so on. And it was on this odd world that Leonardo’s sylvan imagination was allowed to dilate. The ideal court, he seems to conclude, like the free cities of the medieval imagination, is a series of groves or clearings in the gloomy thickets of the world, a knotted harmony of inside and out.

wow that ceiling is amazing! And I had never even heard of it. Lovely

yes, it’s a beautiful thing; heavily restored (after its rediscovery in 1893) – apparently they made it more symmetrical than it should have been. And more recently (1950s?) they uncovered a bit which goes down to the roots of the trees twined in a rocky foundation. Not clear if that went all the way around, but here’s a link to a photo http://www.flickr.com/photos/76518814@N07/6941481364/

What a beautiful room.

This idea that columns derive from trees is pervasive – both Vitruvius and his Renaissance followers write about it, and some of them describe a primal hut, built by Adam after he and Eve were kicked out of the Garden of Eden, built using primitive columns made of tree branches or trunks. But these writers also describe the columns as having human proportions – the Doric, the plain and primal Greek order, is said to be based on Adam’s proportions (and indeed, since the first man was made in God’s image, on those of God too).

So columns are both tree-like and human-like. They take their most literally tree-like form in primal huts, Gothic piers with leafy capitals, and the knobbly wooden supports of cottage roofs and grottoes inspired by the 19th-century Picturesque movement. They take their most literally human form in caryatids, the graceful female figures holding up roof beams at the Erechtheion in Athens, imitated supremely by architects of the English Regency period, from Marylebone to Cheltenham.

I think that must be an early contender for comment of the month Philip!

A carpenter we know has remarked more than once to us that a board doesn’t know that it isn’t still in a tree; it you don’t paint the ends, it will take moisture in very efficiently. For that matter, if you do paint or otherwise finish it all around, it seems to take in moisture to varying degrees in places as humid as Washington, DC–wood doors will stick all summer, then shrink in the fall.

The outside-to-inside design being a reflection of pre-modern political and social life is a very lovely insight.

I love rooms such as orangeries and vineries. Given the popularity of conservatories they’d probably be quite straightforward to create in many homes.

By the way, is it my imagination or is the potted houseplant incredibly unfashionable at the present? I don’t recall seeing any in a weekend mag for ages. Is Susan able to help?

Lovely post…

To lower the tone, there used to be a pub, a mock-Tudor affair, somewhere in south London – I think Streatham – that was built around a tree, a sturdy one, which certainly rose to the roof and at least seemed to grow through it, but whether it was actually a living tree or a dead trunk I can’t recall. It was a long time ago and I was usually pretty drunk. Anyone else remember it? Or maybe it’s still there?

Don’t know it, I’m afraid, but there’s a famous jazz club in Milan called the Capolinea which I went to a couple of time many years ago, and there was a big tree in the middle of that. And I’ve a very vague memory of being in a pub in Nottingham last year which may or may not have a tree in it. Not The Lincolnshire Poacher, I think, although it may have been. Or perhaps it was that very old pub near the castle.