Whether it’s through the drudgery of a yokel or some of the vastest engineering projects ever undertaken, we can’t resist messing around with water. It’s benefited our gardens, cities, crops and sport – but at what cost?

I spend many summer hours watering the plants in my small back garden – plants whose names and properties are unknown to me and for which I take no responsibility whatever beyond this early evening ritual.

The play of waters is not exactly the fountains of the Villa d’Este, and I wouldn’t describe my awe as religious, but I think there must be some atavistic satisfaction – something of the primitive farmer in the soul – about this sudden easy plenitude. In the general run of things, and the recent droughts notwithstanding, being able to disgorge gallon after carefree gallon while you stand motionless, listening to the birdsong and pondering your upcoming beer, is like trampling on the recent grave of winter, and is unquestionably rejuvenating. It is, in fact, about as close as you can get to exercising the power of a minor deity on a daily basis. By contrast, the steady plod with watering can, vital ichor slopping over your boots, is the drudgery of a yokel.

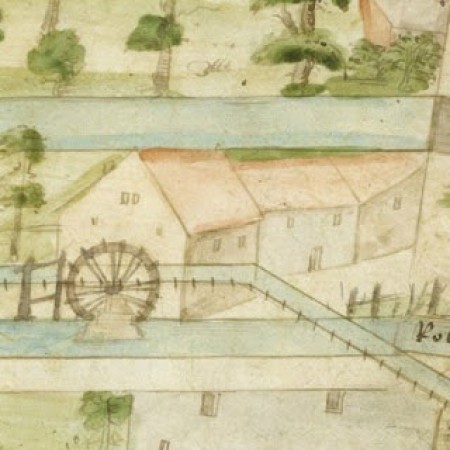

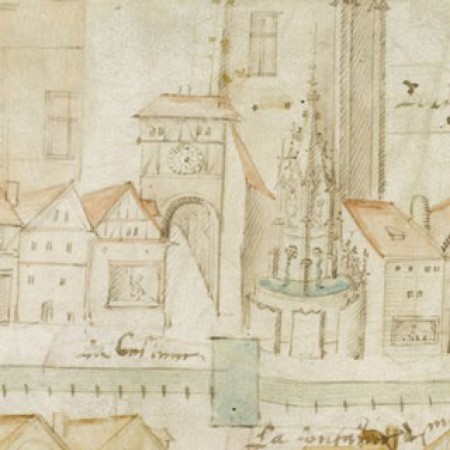

In the sixteenth century the movement of water according to the will of engineers and under the example of the Romans was rightly considered a marvel. Thus in 1525, when the city of Rouen inaugurated its new aqueduct, Jacque le Lieur, one of the town councillors, produced a seventeen-foot panoramic map of the entire course of the aqueduct, in which the structure of the city and its hinterland – its gardens and mills and fields – is bent into shape by the course of the waters.

The completion of the aqueduct in Rouen was also marked by religious processions, masses and thanksgiving prayers. The construction of hydraulic systems, with its attendant metaphors of purification and cleansing, clearly appealed to the general religious sensibility: in Southern Germany after the Reformation, when sculptors working in the great limewood tradition found that demand for their extraordinary retable altarpieces had collapsed, they turned briefly to the provision of elaborate civic sculptures, and in particular fountains, erected like lightning rods for any idolatrous impulses. The supply of water to a town or agricultural project was a religious good akin to the flooding of the Nile.

And of course the converse – denying water or poisoning wells – was equally an act of cosmic aggression. In the early years of the sixteenth century the Florentine Republic, prompted in part by the arguments of its secretary, Niccolò Machiavelli, returned to a project that in conception was at least a decade old: the diversion of the River Arno away from Pisa, Florence’s great enemy.

The original conception, of course, had been Leonardo da Vinci’s. As the Anatomy of Norbiton has it:

Leonardo’s observed world was fluid, dynamical, turbulent; governed by tides and flows and inundation; the soul, or at any rate the mind, was regulated by sluices and dams and reservoirs and locks. His attempts to divert the course of the Arno away from Pisa were not engineering projects but mystical dabbling, and he would have clicked his tongue in approval had he been privy to our knowledge of the secretion of glands, the chemical distribution of emotion.

The canalisation of the Arno basin was never carried through, although a cack-handed start was made (which erroneously supposed among other things that two 15-foot-deep channels would be equivalent to Leonardo’s stipulated 30-foot channel – the waters of the Arno would not adopt the new channels, which anyway soon collapsed). No doubt it was just as well. The emergent effects of such vast works is hard to gauge – the Soviet Union, for example, turned the Aral Sea into a desert by diverting tens of cubic kilometres of water each year to cotton-growing projects. The cotton thrived, but everything else has withered to salt.

My hosepipe will not drain the Aral Sea, but my lush garden’s days may well be numbered, like golf-courses in the desert. The whole vast aqueous system of the watery globe is now credited with a sort of hydro-magical sensitivity. The age-old cataclysmic fear of deluge and flood have been translated into impotent horror at the impossibly delicate balance of elements – warmth and carbon dioxide and so on – such that gulf streams and northern ice and deep currents are understood to be a teetering precarious system, and human intervention no longer beneficent and noble but, sinister, alchemical.

Perhaps a shift of humoural sensibility is indeed indicated, away from the moist and melancholic black bile and towards the hot, dry, choleric yellow bile. Perhaps I should start to plan for a Hot Garden, an unshaded, unblinking place full of dry, motionless hard-baked plants, self-sufficient, unsmiling, but competent.

Not this year, though. This year I will slop the watering can, and watch my green plants wilt and fail in the moderately augmented heat.

Our German friends, as ever a pragmatic race and their water, in the the southern Lander especially, costing a Pfennig or two, save the stuff ‘regenwasser samelen system’, in fancy placky barrels fed from roof collection systems, used for all except drinking, no hosepipe bans there, I hasten to add. We, exiled in Scotland, have no need of such expense or inconvenience.

Car registration number of the bloke who owned Morpeth’s Northumbria Spring Water….H2EAU

Always a pleasure to read! I personally think aqueducts are one of civilisations greatest things; on the grand union canal behind my house the canal goes over the river Avon in a bridge, the act of walking by a river going over a river has something of the m.c esher about it

The great film ‘Jean de Florette’ has the “cosmic aggression” of water denial as its theme, and is almost unbearable because of it.

As Yves Montand unforgettably remarked “quelle eau?” Those Soubeyran’s eh? knew bugger all. Did wonders for A level French though but, and the Provence housing market.

People have been predicting wars over water rights for decades, especially in the Middle East. I don’t believe one’s happened yet. I suppose there are so many more engaging reasons to have a war.

When the war comes I make prior claim to all copyrights for the headline

‘The War of The Hoses!’

Fought around the Cascade mountains.