This week we consider what the abrupt disappearance of a medieval board game can tell us.

To play a game is voluntarily to restrict your own liberty. It is a form of moral discipline. You agree to abide by certain rules which, most likely, you had no part in drawing up and will not trouble yourself to question.

And it would seem that, unlike other forms of moral discipline, the pay-off is more or less immediate, if also more or less superficial. Not only are the outcomes minimally deferred, but the exercise of skill and the distribution of luck occur conspicuously, and in the here-and-now.

However, a game is not a wholly closed or self-contained system. Learning to play chess or cricket or snooker well requires you to think about the game when you are not playing it – in other words to practice, to watch others, to analyse your own performance. And it requires you, moreover, to participate in the history of the game.

Games, like everything else, have a history, and if there are more extinct species of game than there are survivors, this is because their fitness for survival is tied to the wider historical context in which they grow up. A case in point is rithmomachia, the great game of the intellect of the Middle Ages.

Very often in medieval or renaissance art, what appears to be a game of chess is a game of rithmomachia.

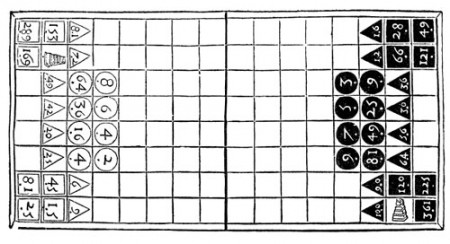

Rithmomachia was played on a chequered board, like chess, but the board was rectangular, not square. Also like chess, it was a game of territory and capture, and an emblem of intellectual prowess.

But unlike chess, it was a game in which the building of harmonious and pleasing patterns was not merely a side effect of the play: it was the whole object. The game was rooted in Boethian number systems, a neo-Pythagorean doctrine of great influence in the Middle Ages, according to which numbers were philosophical entities which lay, in various important and profoundly interrelated sequences, at the heart of everything.

Each player had counters marked with numbers disposed according to various of these sequences – square numbers, triangular numbers, hexagonal numbers and so on – the numbers on each row derived in increasingly arcane fashions from those on the row above:

The object of rithmomachia varied depending on the skill of the opponents. There were eight possible Victories, as they were known – five Common and three Proper. It was agreed at the outset which Victory would be played for. The Common Victories involved counting pieces captured, value of pieces captured, and so on. The Proper Victories were more esoteric, requiring the player to align sequences of numbers in arithmetical, geometrical and so-called harmonic progressions. The highest Victory of all – the so-called Victoria Praestantissima or Victoria Excellentissima – invited players to align four pieces in a row in such a way that all three progressions were expressed therein (examples, for what it’s worth, would be (2,3,4,6), (7,8,9,12) and (12,15,16,20)).

Thus rithmomachia, partly a mnemonic and intellectual aid and partly the proper occupation of a magus or scholar, was bound intimately into its intellectual world. And for this reason, it was rapidly and almost entirely extinguished by the collapse of Boethian number theory, which was ousted by advances in trigonometry and algebra towards the end of the sixteenth century.

We do not exhaust the possibilities of games. The game merely ceases to be relevant. In 1943 Hermann Hesse published his last novel, The Glass Bead Game, in which, in some ill-defined future (perhaps, he suggested, at the outset of the 25th century), philosophers and aestheticians withdraw into monastic communities the better to pursue an ultra-intellectual game, the counters of which are the totality of cultural and scientific– and especially mathematical and musical – knowledge.

Hesse is describing the distaff as he perceived it between action in the world and stoical withdrawal from it; all cultural and intellectual life, he seems to be saying, are a closed system, one in which your manifest excellence is no preparation for an actual life. But the history and especially the disappearance of rithmomachia tell us the reverse: that a game is bound utterly to the wider conditions of its existence. A game is an oblique form of inquiry, not simply an object of knowledge. And sooner or later we will cease to inquire into what no longer interests us, no matter how interesting the form of that inquiry.

After last weeks Darwinian orchestras, this week it’s Darwinian board games! So it appears there has always been versions of ‘dungeons and dragons’

I’ve never played D and D, but I think it’s fair to say they took it pretty seriously in the Middle Ages.

And suddenly it becomes clear what James Mason was refusing… rithmomachia!

Is it fair to say that modern chess is the game with perhaps the optimum level of complexity? Attempts to make it trickier – eg. Capablanca Chess, contrived in the 1920s, which has two extra pieces (a ‘chancellor’ and an ‘archbishop’) – just haven’t caught on, presumably because the standard version provides quite enough headaches/madness…

I don’t know, Brit – Go has a pretty healthy reputation as a bit of a bugger. Ah, but I notice you say optimum, so yes, very possibly. I know that Capablanca learnt chess aged about 2 (or something similarly improbable) by watching his father and uncle play and inferring the rules for himself – apparently when he then pointed out that his father had mis-moved a knight his father challenged him to a game and lost. So it’s very possible he felt the need for something a bit spicier at some point later in life.

I suppose Monopoly is our era’s board game.

Where does Hungry Hippos stand in the evolutionary scale?

I don’t know about the evolutionary scale, but I imagine its a lot more fun than rithmomachia, drunk or not.

Ah yes, the Star Trek 3-D chess set- as available from the Franklin Mint…

3-d? I think you must mean tridimensional. I read that it was introduced in 1994 and was ‘shortly discontinued’, making it a very sought-after item

I remember it well, made of crystal and chrome. Utterly hideous example of what the world would look like if there were no women

Nope, I think there are quite a few of ’em around- I’ ve sold about three of them over the last ten years. Remember that the Franklin Mint’s idea of a “limited edition” runs into many thousands.

This is fascinating stuff – though possibly quite deep and perilous.

A little bit of googling suggests that rithmomachia wasn’t the only medieval or Renaissance game with a pedagogic goal and roots in some pretty ancient cosmological beliefs – rummaging through some interesting but ever-so-slightly nerdy board-game sites, I discover the existence of “uranomachia”, a game based on Ptolemaic astronomy, and “metromachia”, in which the pieces represent various classes of geometric solid. The latter seems to have been a ridiculously arcane pursuit and was played on a board the size of a dining table.

Indeed, there’s even a school of thought that chess originated not from the militaristic model usually assumed but from Chinese or Vedic ideas about astronomy/astrology. The major pieces represent celestial bodies (king =sun, queen = moon, etc.) and the squares are the various astrological houses or mansions.

Joseph Needham certainly took this view in his Science and Civilisation in China and went further by arguing that all ancient board games had a cosmological dimension, as they developed from commonly practised techniques of divination – there being a clear link between throwing of dice and the throwing of lots, etc. Similar, I suppose, to the development of card games from Tarot and other forms of cartomancy.

Needham even anticipates Toby’s Darwinian theory of board-game development when he writes: “Some social anthropologist will produce some day a fully integrated and connected evolutionary story, quite biological in character, showing how all these games and divination-techniques were genetically connected.”

Likewise, an evolutionary biologist named Alex R. Kraaijeveld has made the claim that “board games are like plant and animal species in that they can evolve and give rise to new forms …Obviously, board games can also go extinct and they even have their ‘fossils’: games that are not played anymore today, but are known (completely or partly) from historical sources.”

As the “board games equivalent of a brontosaurus fossil” he cites a Japanese game called Tai-Kyoku Shogi – which apparently required a board of 1296 squares and over 400 pieces per side.

And Worm, your “hideous example” etc. made me laugh out loud, thanks.

Extraordinary – seems I only scratched the surface. Metromachia sounds like my sort of game. Thanks for all that Jonathon.

I don’t think I was making a Darwinian case, as such (although it seems to me self-evident that cultures evolve, that cultural practice has heredity, and that selectional pressures apply to cultures in the same way as species); I was just musing on the connected fate of rithmomachia and Boethian number theory and may in consequence have over-stated my case – Hungry Hippos, for instance, is possibly not so deeply rooted in the culture of the 1970s as I seem implicitly to be suggesting.

I’d hazard, however, (entirely without evidence) that the shift to computer/console gaming has meant more than a simple proliferation of new forms – specifically, there’s been a move away from abstraction towards role-play/contextual play, where everyone is now a generalissimo, a grunt, a football manager, a gangster, and so on; there are some exceptions of course – Tetris springs to mind; but even a game like Angry Birds is sufficiently context-rich to offer (slightly depressing) small-world possibilities to my five-yr-old.

I don’t know what to conclude from that, but if it means fewer Bridge parties, the world will be a slightly saner place on balance.