In this week’s bulletin, Toby Ferris explores Norbiton’s sympathy with non-existent but thinkable fauna…

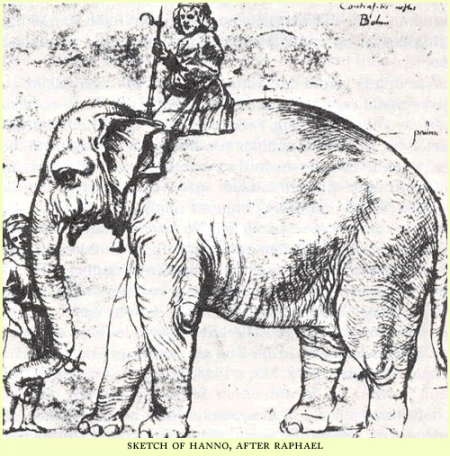

When Hanno the papal elephant died in 1516, Cardinal Ippolito d’Este tried to obtain the bones for his collection of naturalia.

He failed. The animal was interred in the Belvedere under a memorial fresco painted by Raphael and with an epitaph written by Pope Leo X himself, who had been present at his death.

Elephants were marvels – Hanno was particularly noted for his pale, almost white colour – but they were not particularly rare. Unlike the giraffe. In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, strange beasts were the currency of princes, but giraffes were notoriously difficult to get hold of. Lorenzo the Magnificent, however, obtained one, fruit of a futile diplomatic manoeuvre on the part of the Mameluks to secure Florentine aid against the Ottomans. From contemporary accounts it seems the giraffe was at liberty to wander the streets, and it appeared to enjoy the adulation of the crowds it drew.

What is odd about these scenes – the crowds mobbing the giraffe in Florence, the Pope watching his white elephant die – is that we can easily visualise the animal in each case, but not the human protagonists. An elephant is an elephant, more or less, and a giraffe is a giraffe: there is little scope for change in five hundred years or so. The streets of Florence in the fifteenth century are to us almost unimaginable, but a giraffe ambling around them is, unexpectedly, in accurate focus, almost as though it were an emissary from our own time. Which is as much as to say, I suppose, that in the great welter of creation we stand closer to the giraffe than we do to quattrocento Florence.

But perhaps, after all, that is not quite true either. A giraffe or an elephant in the Renaissance was, culturally, many things – semioticians, those fabled beasts of our own day, could no doubt make much of them as empty signifiers to which a variety of meanings could be appended – and cultures have histories, they are apt to mutate. Thus in the fifteenth century the giraffe, vaguely associated in the bestiaries with the camelopardolis, a beast half-camel, half-leopard, acted as a bridge to the uncategorised totality of a vast but finite and comprehensible cosmos, in a way they no longer can. Giraffes for us do not have that estranging power. We might get a better sense of what Lorenzo the Magnificent saw when he looked at a giraffe, if we consider not at a giraffe at all, but, say, a Tapir-Nymph.

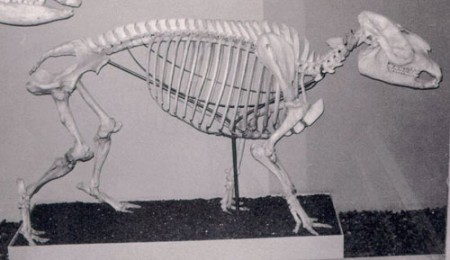

The Tapir-Nymph or Tapir-Iauare is the yeti of the tapir world. Cryptozoologists explain that it is an aquatic carnivorous tapir which lives in the zaniest corners of the Amazon basin; they speculate that it is a remnant of the mesonychids or hoofed carnivores which flourished between the Palaeocene and the Oligocene. It hunts alone or in small groups, beats its long cow-like ears on the water to alert its companions of danger, and can carry off a small caiman.

Needless to say, the beast has not yet been described by science; but then in fairness to cryptids generally we should consider that the gorilla was only described for the first time in 1847, and Baird’s tapir in 1843. We will not be able properly to establish their non-existence until we eliminate the Amazon forests. Even then, perhaps, they will continue to thrive, in the fishy depths of the internet, or of the past.

The fifteenth-century giraffe existed and the twenty-first century Tapir-Nymph probably does not, but in many ways the fifteenth century giraffe stands closer to the Tapir-Nymph as a cultural object of knowledge than it does to the twenty-first century giraffe, the commonplace and disregarded furniture of nurseries. Norbiton does not have a cardinal, nor does it maintain a cabinet of curiosities in which to house the whitened bones of a tapir; but it is sympathetic, in imagination at least, to the impossible Plinian project of a catalogue of the cosmos and its mutable effects, among which it must now number both non-existent but thinkable fauna, and unknowable historical moments.

Great piece. There is, via google book search, a lengthy discussion of the Tapir-nymph here http://bit.ly/wCA5IF in what looks like a fascinating book: The enchanted Amazon rain forest: stories from a vanishing world by Nigel J. H. Smith

You do write beautifully Toby! And your piece immediately put me in mind of the book The Pope’s Rhinocerous by Lawrence Norfolk, which deals with similar subject matter regarding bestiary in the renaissance consciousness. (although I must say I found it rather tortuous and gave up half way through)

Thanks both, very much

I didn’t know either the Smith or the Norfolk; in the Smith I see there’s an account of a tapir nymph swimming ‘with the grace of an otter’, which I wish I could have quoted – also the suggestion of a local fisherman that it could use its body-odour to overpower prey.

My sources, I’m afraid, are much less authoritative – especially where the Tapire Iauare was concerned (loony websites, I suppose appropriately, one of which seems to have drawn on the Smith). Seems, from what I can gather, that the discovery and description of new species, like the attribution of works of art, is a practice always bordering on charlatanism and chicanery – there’s this, for instance, ( http://www.marcvanroosmalen.org/dwarftapir.htm ) on the discovery of a new tapir species in 1990, by a scientist who, I read elsewhere, offered to discover and name species (mostly of primates) on behalf of rich benefactors, more or less to order.

Splendid awesomeness once again.

There are tapir at Bristol Zoo (a place I visit so frequently, thanks to free membership via wife, and young children to take, that I’m on familiar nodding-terms with the monkeys) but even more myth-like are the okapi. I thoroughly recommend clapping eyes on an okapi if you get the chance.

thanks Andrew – you’ll be delighted to learn that cryptozoologists make much of the okapi, its existence having been a matter of much dispute at the end of the nineteenth century – Wikipedia tells me the now defunct (or perhaps just hiding) International Society of Cryptozoologists adopted the okapi as their emblem.

They have okapi at London Zoo – if I remember they were just round the corner from the solitary Malayan tapir, but I haven’t been for a few years.

What about the Gnu? Or the pushmi-pullyu?

I read that the Gnu is in fact the Wildebeest. The cosmos just got a bit simpler.

As for the pushmi-pullyu, I’ve never seen Dr Doolittle, and I don’t know how Rex Harrison landed so many singing roles, but this duet with Richard Attenborough is admittedly a bit special http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=niKkURpdzIQ&t