The Atlas of Norbiton is a weekly bulletin from Norbiton: Ideal City of the Failed Life. Unlike its more comprehensive, detailed and discursive mother site, the Anatomy of Norbiton – hailed by Nige as “a thing of strange beauty and wonder, inspired by the South London nowhere known as Norbiton” – the Atlas is intended as a pocket guide to the Failed Life for Failed or Failing Individuals on the move.

I always put my spectacles on to look at paintings. I have a slight astigmatism which almost imperceptibly blurs detail, and which requires correction for proper full-on fine-grained looking. I sometimes find myself wondering, however, if I really am seeing what I am looking at, or if I am experiencing only an artfully deviated and tinctured stream of photons, a mimicry of the correct functioning of an eye which never in fact existed.

And so from time to time in front of certain paintings I will remove my glasses, to satisfy my superstitious need to see the object with my own eyes.

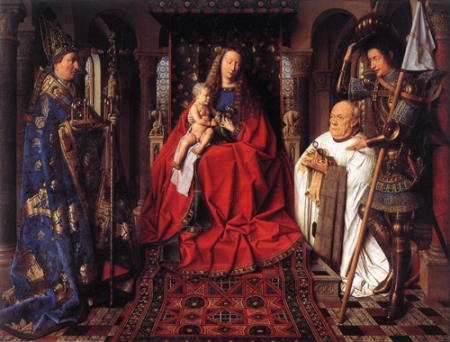

Not long ago I was in Bruges and went to look at van Eyck’s Madonna and Child with Canon Joris van der Paele (1434-6) which hangs there in the Groeninge Museum.

I put on my glasses of course, and surrendered to the welter of detail. Van Eyck was by training a miniaturist, an illuminator of manuscripts, and there is in his work a universally unfolding clarity at all resolutions, on every scrap of every panel, whether you stand yards back and let your attention rove over the whole, or press your nose up against the painted surface.

I did not press my nose up against the painted surface, chiefly because my behaviour in public is more usually conventional than not; but the painting is in any case protected by a sheet of toughened glass placed about four inches from its surface. They are not too regular with the Windowlene in the Groeninge, I’m afraid to say, and my glasses tend to the smeary, so my view was fractionally compromised by a misaligned sequence of smutched layers.

The Canon, by contrast, has no such problem. He has taken his spectacles from in front of his watery orbs, the better to contemplate the blinding clarity of his vision. No longer does he look through a glass darkly, or wander the shaded labyrinth of theology and faith laid out in his books. He merely takes it all in with his own eyes. He finally, properly and unambiguously sees; reads in a single gulp of the eye the layered typological patterns.

To see something with your own eyes used to be the touchstone of knowledge. It no longer is, because if we wish to penetrate the cloud of unknowing and properly grasp the fundamentals of the universe, as Canon Joris does here, then we need to deal with particles so small that the least interaction with a photon will fundamentally alter them. There is, in a real sense, nothing to see.

Or at any rate, nothing to see with our own eyes. The scientific revolution of the seventeenth century was founded, in some accounts, on the invention of the telescope and microscope more than on any prior shift in paradigms of rationality. It is as if, to properly see, we need not to correct but to multiply our modes of looking – up to and including looking, so to speak, with mathematics – and I have to that end occasionally stood in front of paintings with a pair of binoculars. Similarly painters often use mirrors to check the progress of their work, its proportions and symmetry. Perhaps this multiplied looking is a condition of understanding. Glasses on or glasses off, I should not worry.

My brother, who happened to be standing next to me while I was looking at the van Eyck, and who doesn’t wear glasses if that is in any way significant, has a different reading. According to him, the Canon has taken his glasses off as a point of etiquette, and now cannot see anything at all. What the painting captures therefore is a moment of embarrassment – the Canon about to address his respects to Saint Donation’s mitre, for example – rather than a moment of clarity. And that could in turn explain why St George feels the need to doff his helmet, rather in the manner of Monsieur Hulot trying to put the peculiar company at its ease.

Perhaps my brother is right to mock in this way my blither about the removed spectacles being a synecdoche of universal clarity, a clarity now lost to us even in imagination. But before we move on to other paintings, I take off my glasses and peer around the side of the protective glass. I have now seen the Madonna and Child with Canon van der Paele with my own eyes. I can rest easy.

the detail on the canon is fantastic isn’t it! The wispy hair and eye wrinkles are almost photographic

You could be right. I’ve mislaid my glasses.

It’s amazing how many subjects of these Flemish paintings look like Rotarians.

Yes – Rotarians who’ve been abducted by aliens

Ah but did you really see it with your own eyes, since there was still the toughened glass twixt it and your eyeballs, wasn’t there?

More Dabbler van Eyk here.

Ah well no, the painting isn’t in a box; the glass is projected out from the panel on four metal brackets, if I recall, so when you peer round the side of the glass you can set eyes on the real actual unmediated thing itself. You can’t actually see much (anything?) of the painted surface, of course, but you can commune with the full presence of the object in a mystical sort of way, if that’s your bag.

The canon suffers from the far-sightedness of middle age, and so needs his glasses to read the book he is holding. But Madonna and Child are arms length or a bit more, so he can see them clearly unassisted.

Yes of course. That hadn’t occurred to me. It may also be true that the damage to his eyes was professional – he was a scriptor at the papal curia in Rome as a younger man.

I’ve no doubt succumbed to the temptation to read van Eyck as though it were Velasquez (optics, mirrors, epistemological woe). In my defence, it’s an easy mistake to make. The text at the top of the frame is from the Apocryphal book of Wisdom of Solomon 7:26 which says of the Madonna ‘For she is the brightness of the everlasting light, the unspotted mirror of the power of God, and the image of his goodness.’ There’s a miniscule reflection of the painter/spectator in a fragment of George’s armour. And I don’t think you can make it out from the reproduction, but the glasses slightly distort the text which they overlay.