In this week’s bulletin from Norbiton, Toby Ferris considers the remarkable Linear City of town planning visionary Arturo Soria y Mata…

Town planning is predominantly a literary form. The boiling visions of the great city planners remain for the most part locked on the page, quaint and harmless. Writing, insofar as it is a way of bringing the imagination to heal, offers the planner a medium in which he can – imaginatively – tame the baroque and unpredictable growth of the city, and vent his own mania for order.

This is a great pity, of course. The world would be more picturesque were it filled, like Calvino’s Empire of the Great Khan, with Ideal Cities, and Floating Cities, and Radiant Garden Cities Beautiful. But wherever a visionary plan does intersect with the empirically real city, it is rapidly overwhelmed, subducted. Ideal geometry is no match for people, or capital, or time.

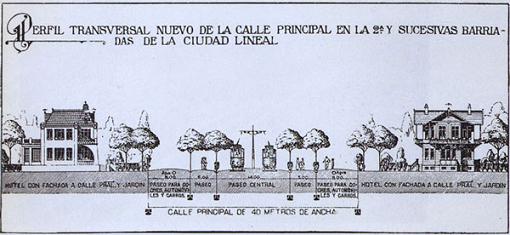

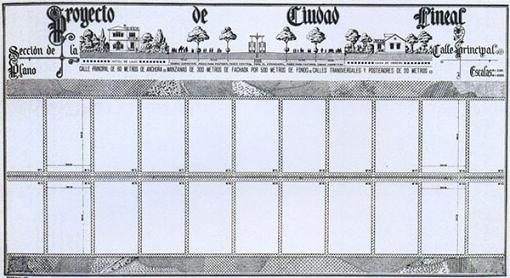

Take for example the Linear City of Arturo Soria y Mata. In a series of articles from 1882 onward, Soria theorised a single developed strip of no more than 500 metres in width, with a central tram and roadway and residential and commercial plots on either side of stipulated size and separated by smaller streets, at the intersections of which there would be kiosks and shops, and in the centre of which there would be schools, hospitals, courtrooms and so on as need determined. No point in the city would be more than a few hundred metres from the countryside.

This five hundred metre strip could be as long as humanity required, might ultimately stretch from Cadiz to Saint Petersburg, from Brussels to Peking.

His vision was to unwind the city. In part this was a pragmatic response to the insanitary conditions of the industrialised cities of the nineteenth century, which he regarded as compacted, compressed and diseased organisms lacking proper anatomy. The Linear City, by contrast, would be a strong, healthy, vertebrate animal.

But Soria’s underlying organisational impulse was as ancient as cities themselves – the hankering for a rational civic geometry. Not a geometry in this case of ideal forms, but one which respected the underlying linear forces of the modern city: the railways and tramways, the telegraph and telephone, electric light and steam heat. The city had become an interlacing of lines and networks, draped inappropriately and uncomfortably over antique nuclear cities.

And it was not only rational to give play to the fundamental linearity of the city: it was moral. The straight line sanitizes, purifies, cleanses, it opens up to the light and air: there was to be no more rotten innerness. The straight line – the linea recta – had become prime in all planning.

In 1894 Soria managed to found a company, buy some land to the East of Madrid, and start work on his tramway. The initial plan was for a 55km belt running North to South which would act as an attractor for suburban development, but Europe was already old, all the land had been parcelled up long since, and it proved impossible to put together more than a 5km stretch which was no sooner completed that it was absorbed by the wholly unplanned and riotous expansion of the city.

Of course the Linear City was doomed not only by the contingency of Madrid’s expansion: it was corrupted by its own rationality. Unlike the Linear City, the world is three-dimensional. Thus any connection with an object lying outside the axis of the city – a source of raw materials, an outlet to a port – will create a node, a gravitational point, an attractor; the gentle pulsing flow (trams!) along a single trajectory will be interrupted or diverted, in places it will coagulate, atrophy, and in places accelerate, vivify. It will become, in other words, a city.

The Ciudad Lineal itself is now a leafy district of Madrid, ranged around the Calle Arturo Soria – as though his giant bones had been laid out and petrified.

It will no doubt amuse psychogeographers to think that the original linear city is still there, hidden, silently determining the health and well being of the (wealthy) inhabitants, as though Letchworth Garden City had become a near invisible suburb of London. But perhaps the reintegration of the Ciudad Lineal was apt. Soria was aware that all cities were now, in a sense, linear; perhaps he merely latched on to something that was anyway happening, the gradual opening out of the city. He simply states the logic more clearly. In his mind’s eye, the city is no longer a place of tortuous possibility, a garden of forked paths, but a contemplative ritual cursus, a salutary treadmill of the spirit. And while this is an interesting thought, it is of course a wholly literary one.

Last week I had to drive to Poole in Dorset and there was a very long, straight stretch of tree-lined road – the A350 I think, presumably a Roman road? Driving so far without doing any turning gave a strange, nameless pleasure.

On the subject of straight roads – there’s an interesting section of Joe Moran’s ‘On Roads’ that talks about the way that the original M1 was built to be as straight as possible. After a few months of opening, they realised that the straightness of the road was causing accidents due to the boredom caused. It also has some strange perceptionary effects too apparently. From then on they then dug up sections of the motorway and put in carefully calculated curves in order to engage the driver and keep them awake. There are still some straight sections of the M1 left though, between Luton and Hemel Hempstead.

As for hairbrained urban planning – I’ve seen a truly terrifying vision for Paris by Le Corbusier somewhere online. Thank god he didn’t get his way

Bruce Chatwin writes a lot (in The Songlines) about the necessity of the hypnotic walking rhythm to what is essentially still a nomadic species. Perhaps a long straight drive accesses that in some way or other – steady pace, broad sky, unchanging horizons. Wildebeest. Ok, long shot.

Le Corbusier’s cité radieuse derived quite a lot from Soria’s linear city, I believe, with just a bit more segmentation/zoning (and it wasn’t so long). Nasty business. Town planning always seems to veer towards social engineering – I don’t know the extent to which it did with Soria, although he was very concerned about fixing global problems of land tenure with his ludicrous city. Jane Jacob’s parody of the Radiant Garden City Beautiful (in The Death and Life of Great American Cities) took Le Corbusier as the epitome of all the evils of planning (and specifically zoning) , although I don’t think she mentioned him by name.

When I play with my three year old daughter’s wooden railway (complete with stations, houses, church, ambulances, cars, massively disproportionate human figures etc) it’s initially satisfying to impose order on the imaginary city. The tracks only allow you limited variation, and so (pushing my daughter aside so I get get on with it properly) I play with uber-fascist constucts where all buildings are in a row along a track… then others where the houses are ringed around a perfectly spherical railway, a kind of hermetically sealed world in a never ending circular motion. Then I panic and crave disorder, wish there were external forces (hills, rivers, conservation areas, portest groups, hippies tied to trees) that would cause the tracks to bend and meander in an apparently chaotic way. So it’s almost a relief when my dog suddenly makes off with a wooden woman in his jaws – a sort of Godzilla come to give me a reality check and shock me out of my linear delusions.

(I need to get out more).

Nice piece by the way, as usual.

god complex much, Gareth? 😀

I remember when I was very small in the 1970s coming down to the living room one morning to find that my father, who had already left for work, had stayed up into the early hours, fuelled probably by whisky, building a perfect and extensive lego town with a railway and those illuminated bricks you used to be able to get. If my oedipus complex had been better developed I’d have understood that he was really just driving tyrannical order through the kingdom of the little people (me and my brother), and have tied myself to a tree. Or kicked it all over. But I loved it. Le Corbusier could probably have told a similar (or inverse) story, about pushing his ham-fisted father out of the way and producing a match-stick Swiss village overnight to the amazement of his elders.

There’s a good picture of le Corbusier in godzilla mode here

http://anatomyofnorbiton.org/other%20pages/on%20Town%20Planning%20in%20the%20Ideal%20City.php#clarkeoncorbusier

And on the subject of Godzilla and the Ideal City, there’s this

http://anatomyofnorbiton.org/prospectus%20-%20otium.php#noveltycyclops