This week Jonathon faces the lexicographer’s greatest fear: popular etymology…

Humankind cannot bear too much reality.

T.S. Eliot Four Quartets

The word coiner, in the sense of counterfeiter, is first recorded in 1578. No doubt the result of an oversight (perhaps mine, I may have missed it) the current OED, source of this date, offers no direct mention of coin as a root verb meaning counterfeit, noting only that coin, which had meant the stamping out of legitimate money since c.1330, could from 1589 also mean ‘To frame or invent (a new word or phrase); usually implying deliberate purpose; and occasionally used depreciatively, as if the process were analogous to that of the counterfeiter.’ Slang meanwhile had bene-feaker, literally ‘good-maker’, which, like coin/coin, can be seen as simply extending a standard use into an criminal one. To coin a phrase, i.e. to invent one, arrives around 1810. It seems restricted to the positive inference; to make up something both new and, faut perhaps de mieux, trustworthy.

Which trust may be misplaced. Not so much in the words or phrases themselves – there they are, this is what they mean – but in the legends of their creation. The lexicographer aims at accuracy, but there remain two words that strike fear into the professional: popular etymology.

I cannot boast Eric Partridge’s voluminous correspondence – the modern world lacks, I suggest, a sufficiency of ageing gentlemen with inquiring minds and time on their hands; and in any case, in a world of instantly available blogs, why suggest, let alone ask when one can pontificate. But I get a trickle of mails. These do ask, but even more they suggest. Etymologies, stories behind words. As often as not these stories run counter to the canon, which in etymology as published one hopes is the product of informed research. I do not wish to belittle my correspondents, I am grateful for their contact and in a world of relativism, many might ask why should my etymologies, or indeed those of the OED be any ‘better’ than anyone else’s. But better is not the point, ‘as correct as one can manage’ surely is.

Etymology seems particularly prey to speculation and it has afflicted professionals as much as amateurs. The author of 1689’s Gazophyllacium (lit. ‘strong-box’ or ‘treasure-chest’ and as such synonymous with thesaurus) believed among other propositions that ‘Hasle-nut [comes] perhaps from our word haste, because it is ripe before wall-nuts and chestnuts’ and ‘Hassock, from the Teut. Hase, an hare, and Socks; because hair-skins are sometimes worn instead of socks, to keep the feet warm in winter.’ This was certainly published – it may even have been believed. America’s Noah Webster believed quite firmly that there had been a single ur-language, from which all the rest had emerged: ‘before the dispersion; the whole earth was of one language and of one or the same speech.’ This language he christened Chaldee, ‘the primitive language of man,’ and it was spoken by ‘the descendants of Noah.’ Webster knew what was happening in German philology, fuelled by Sir William Jones’ researches into a real ur-language, Sanskrit, but an American, dead-set on promoting a national tongue, had no time for ‘old Europe’. He blundered on and was mercifully dead when in 1864 a major revision of his work stripped out his Bible-based egregia.

More immediately, and back to slang, researchers have to contend with the beliefs of the French writer Alice Becker-Ho, former partner of Situationist Guy Debord, who is determined to shoehorn the entirety of European slang into Romani origins, and of the late Daniel Cassidy, an Irish-American of fiercely nationalist bent, whose book How the Irish Invented Slang attempted the same task on the basis of his own predilections. I enjoy Ms Becker-Ho, whose introductions see off her opponents in fine style. I wrote to Mr Cassidy. I could understand, if not agree with his suggestions based on 19th century New York City, but had a problem with those that took unto his fellow-countrymen the London cant of the 16th century. He seemed to lack the time to reply.

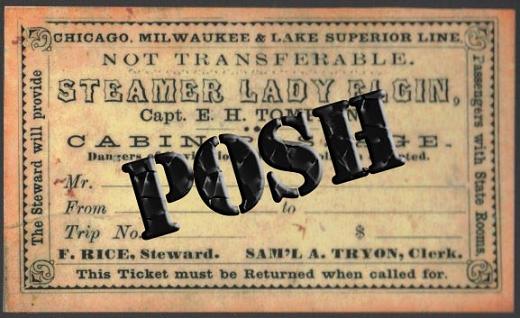

And of course, far, far from academe, the flow of reinterpretations of such eternal delights as OK, jazz, posh, and the whole nine yards can never be dammed. (In fairness, the last of these still defeats all-comers.) So too the obscenities. No Virginia, there was never an ordinance regarding ‘Fornication Under the Command of the King’; and while you’re at it, forget that Agincourt stuff about ‘pluck yew’. Nor were sailors ever instructed to ‘Ship High In Transit’ such materials as might produce explosive methane gas and Thomas Crapper was merely blessed with a job-specific surname. One may gain a momentary amusement from the ingenuity, but not the persistence of such absurdities.

It should be shooting fish in a barrel, but on occasion such fish are living in aquaria and lovingly nurtured therein. And backed by a mix of seemingly wilful misinterpretation and definitely self-serving agendas, these otherwise blatant errors seem no longer susceptible to the derision they deserve, But I am sorry, ignorance is still not bliss, however politically correct. Picnic does not come from a plantation-era command to ‘pick a nigger’; nitty-gritty does not refer to the detritus of a slave ship’s hold, nor does niggardly have the slightest link to negritude. (And no, I would never exclude Jew, whether down or out of from my dictionary.)

In the end, of course, the big question is: why? Why do we remain so dissatisfied with what dictionaries, supposedly founts of knowledge, have to offer. It isn’t simply the relativist thing, so much encouraged by digital life, because these arguments are age-old. Maybe it’s the belief something’s always better than nothing: especially as regards slang which, in the OED, so often faces the chilly realism of ‘etymology unknown’. These are only words, ferchrissake, we need to know whence they came. I notice just over a thousand ‘ety. unknown’ in my own work. No more than 2% of the headwords. Perhaps I’m over-enthusiastic too.

Anyway, did you know that golf comes from ‘gentleman only, ladies forbidden’. Yes, really…

The final sentence Jonathon, is devastating, for those wearers of blue blazers with brass buttons and grey slacks(or gray slacks) I would imagine that lexicography, once embarked upon, is a never ending round of one question answered, six more raised.

I’ve been admonished for using ‘nitty-gritty’ but protested that the slave ship interpretation was a myth. There then followed a philosphical discussion about whether the veracity of the origin actually matters, if enough people decide that that’s what it refers to, and therefore take offence…

On the subject and slightly off the subject, the French political correctness inspection dept are ganging up on their language, considering that the French think of it as untouchable, quite surprising. Wags may point out that the legions of right little French madams are now in fact, right little madams.

I believe this philosophy was espoused by Hitler and then Goebbels who embraced the concept of ‘Große Lüge’ (the Big Lie). OK, that may be alarmist. And of course the language changes and we lexicographers have no choice but to etc etc. But not (fortissimo to end) when such a change is propagating bullshit. Note to self: do I have intellectual capacity to post on this next week?

You’ll be saying that ABBA doesn’t stand for Agneta, Benny, Bjorn and the other one next.

A truly fascinating area, this; why is it, I wonder, that these legends seem to attach themselves especially to words with ethnic (or allegedly ethnic) meanings? I’m thinking of the numerous dodgy explanations for ‘spic’ and ‘gringo’, for instance …

That said, my favourite piece of spurious etymologizing is probably Dr Johnson on the subject of ‘antimony’:

The reason of its modern denomination is referred to Basil Valentine, a German monk; who, as the tradition relates, having thrown some of it to the hogs, observed, that, after it had purged them heartily, they immediately fattened; and therefore, he imagined, his fellow monks would be the better for a little dose. The experiment, however, succeeded so ill, that they all died of it; and the medicine was thenceforward called Fr. antimoine antimonk.

Thank you Jonathon for the terrific read

It must be nearly 10 years ago now that I received a Christmas present of a ‘toilet book’ on etymology (by some chap called Albert Jack if I remember correctly). Well, after approximately 10 pages I gave up and took it down the Oxfam, as it was obviously just a bunch of hearsay and hokum. Very disappointing.

Interesting when in Australia to ask people their idea of the etymology of the word Pom – it seems literally everyone has their own slightly different spin on it.

It’s a good rule of thumb to say that any etymology for a pre-20th century word that depends on an acronym is codswallop.

(That’s codswallop from the inferior beer or wallop brewed by a 19th-century Mr Codd, innit; and, as everyone knows, rule of thumb from that very elusive statute — reign, date, section, paragraph? — saying that a man could legally beat his wife with a stick no thicker than his thumb.)

Have you ever thought of taking this up as a profession, Jon? And if so, very sensibly thought again.

For fear that SJ’s antimony will be off around the net as truth. I offer the OED’s effort:

Probably, like other terms of alchemy, a corruption of some Arabic word, refashioned so as to wear a Greek or Latin aspect—perhaps, as has been suggested, of the Arabic name uṯmud, aṯmad, itself, latinized as athimodium, atimodium, atimonium, antimonium. The earlier form of the Arabic is iṯmid, in which Littré suggests an adaptation (quasi isthimmid ) of Greek στίμμιδα variant of στίμμι, whence also Latin stibium. If this conjecture be substantiated, antimonium and stibium will be transformations of the same word. ‘Popular etymology’ has analyzed French antimoine as ἀντί + moine against the monks (‘monks’-bane’), and, as usual in such cases, supported the derivation by an idle tale (see Johnson), making the name originate (more than 400 years too late) with the chemist Basil Valentine, in end of 15th cent.

The Great Lexicographer really went to town on the word: as well as the etymology he then offers around 30 lines direct from Chambers’ Cyclopedia, still something of as state-of-the-art work. He does not, however, even hint that his ety. may be spurious.

My god, Jonathon, you are a genius and I love your enthusiasm. This is the sort of stuff that will go down in history, so long as cyber warfare or a strange solar flare doesn’t blot out our electrics for a few thousand years. Or someone fails to pay the hosting fee when we’re all dead and gone. I wish I had time to read and research your posts more thoroughly, there’s so much in here… it’s extraordinary.

And I even thought I saw mention of David Cassidy, but then I saw it was Daniel. By the way, where does ‘netball’ come from? Could it be ‘nuts excrutiatingly throttled by athletic livid ladies’?

As regards etymology netball is tediously prosaic and one receives only that simple two-word compound which is inscribed on the box. First OED use is 1900, when it mentions a game being played at the Alhambra Music Hall, which among other stars offered Jules Léotard, the original ‘daring young man on the flying trapeze’, show-cased the can-can and was much-admired by gentleman callers for the friendliness, mercenary or otherwise, of its ballet-girls. One wonders as to the prototype netballers’ uniforms. On the other hand, in 1923, we find the Daily Mail declaring that ‘Net-ball enjoys considerable popularity. It has the good points of lacrosse, but is less strenuous.’