Elberry puffs his way through a new and much-hyped short story collection…

Short stories, like poems, are easy to write, and like poems they are usually worthless. Brevity tempts the would-be writer – easier to write a 5,000-word short story than a 100,000 word novel; and brevity makes the poem and story very hard to write well. The reader will forgive the novelist a weak chapter; a short story is so concentrated that every sentence must count, every observation serve a purpose, and this is not so easy. I also hope for a poem-like clarity and force from short stories, whereas novels can simply entertain and amuse. The shorter it is, the more I expect.

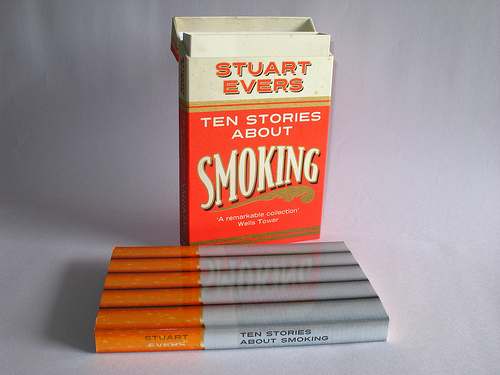

That said, I tried not to expect too much from a book that looks like a pack of cigarettes. The usual hyperinflation on the back: “Stuart Evers winds a course through worlds of yearning, secrets and mortification in prose as lithe as a ribbon of smoke” (Wells Tower).

With very low expectations, however, I found this an enjoyable collection. Smoking features in each story but it isn’t a gimmick; it’s rather as if Evers sees cigarettes as a natural part of many human lives, like booze or death or television. The stories are largely realistic, rather drab, modern, unglamorous, full of failed relationships and regret. A man tracks down his hitherto unknown half-brother only to find their father sired countless children and the half-brother is by now quite fed up with people turning up and expecting hugs and truths. A woman contacts an ex-lover for a last fling before marriage, and is crushed to find he no longer smokes, no longer has the same car, that he is in fact no longer exactly the same. A man buys black market cigarettes from a Ukrainian woman, is drawn to her, and then she disappears without trace.

In my favourite, Things Seem So Far Away, Here, a dysfunctional, smoking hipster called Linda turns up at her rich, non-smoking brother’s mansion, trailing some unmentioned psychiatric episode. She loves her niece and hopes/plans to be offered a babysitting job, despite her apparent instability and weirdness. This story is the strongest and suggests Evers has real talent. The hipster is both sympathetic and alarming; the disconnect between her imagination and reality is subtly and poignantly told:

The sun was going down, the amber light licking at the water in the swimming pool. From absolutely nowhere, Linda got a violently precise image of living there; of being a functioning part of the family. Picking up Poppy from school, cooking dinner for Christine and Daniel, pouring them a glass of wine when they got home strafed and exhausted. Then leaving them to eat as she got Poppy ready for bed, reading her a story before they kissed her goodnight, stories that would give her a love of books. There would be Enid Blyton and Roald Dahl, The Wind in the Willows and Alice in Wonderland. And in the summer she and Poppy would swim together in the pool, splashing each other and screaming. She saw them both there, ghostlike and transparent in the water, their faces alight with happiness. Yes. That’s the way it would be. She could see it so clearly.

This is a story that repays re-readings. Smoking is crucial here, as a symbol of a way of life, or rather how Linda is perceived by the rich and (physically and mentally) healthy: as a grubby, yellow-fingered aberration; and she comes to see herself so. This kind of symbolic vision is poetic and rightly belongs to the short story. The use of cigarettes in this collection is often very well-managed: in these tales of failed connection, where language is impotent, smoking is an act, expressing that which cannot be said. So in Real Work a worthless conceptual artist makes a video juxtaposing news footage of violence with explicit pornography. For such an artist, words are hollowed out, as indeed is everything.

For a moment there was silence. Then the applause began. James, Johnny, Jimmy, Davey, Mickey, Jane and Iola looked almost tearful. As one, the crowd turned to you in congratulation. As I was brushed aside by well-wishers, I overheard someone say: “Sex and death. So simple, yet so…expressive.” Another voice: “The use of split screen, such duality, was inspired.” And another: “It says all it needs to say about our obsession with masculinity.” And another: “The artistic eye is uncanny. It’s naked; both beautiful and ugly.” And another: “This is one of those moments, you know? A real where-were-you? moment.”

The story details the conceptual artist’s descent from earnest student bullshit into the advanced, Turner Prize-like echelons of very marketable, very profitable bullshit. The narrator observes. Earlier, he had joked with a friend about the B-movies where characters go out for cigarettes and are never seen again. So when his conceptual bullshit girlfriend celebrates her grand porno success, cigarettes replace words:

I picked up my jacket. “I’ll see you later,” I said.

“You’re not going, are you? You can’t go yet,” you said. “There’s loads of people you need to meet.”

“I’ll see them later,” I said. “I’m just popping out for cigarettes.”

An act can replace explanation, a symbol can express a complex of emotions and decisions. This awareness isn’t yet fully developed, at least not in all the stories. It is a debut, however. If the collection isn’t as overwhelmingly amazing as the blurbs would suggest, it is nonetheless promisingly enjoyable and grubbily human.