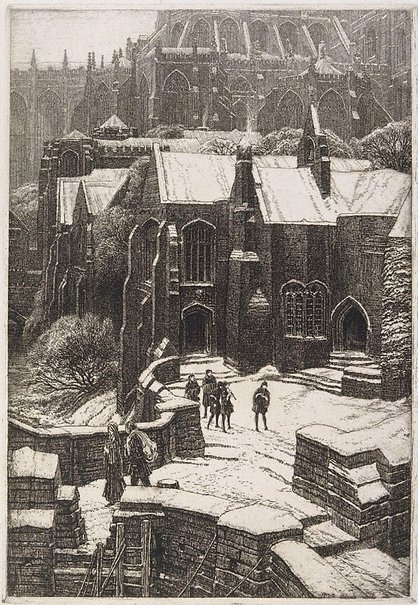

An eerily perfect etching casts a chilly spell over Jonathan Law.

Winter in the cathedral city – somewhere in the north of England, some time (we might guess) in the earlier 1500s. Gothic structures rise from the earth, rear ponderously skyward, and lose themselves in the glistening, frosty light. Snow on the ground, on the dark stonework, and ranged precisely along the thin branches of trees. Little sign of Christmas cheer, you’d say – but wait, though you can’t hear them, the small human figures at the centre of this wintry world are playing and singing a carol. In the left foreground, a man and a woman press on through the cold having received alms; almost, it might be, Mary and Joseph.

I first came across The Almonry – an eerily perfect etching by the English illustrator F. L. Griggs – in the pages of Peter Davidson’s book The Idea of North; it has cast a chilly spell on one small corner of my mind ever since. Davidson’s book is splendidly hard to categorize but perhaps best described as an exploration of the idea of ‘the North’ as reflected in the work of artists, mythographers, writers, and film-makers from antiquity to the present (with a particular emphasis on the 1920s and 30s). For Davidson, “North” is less a real place than an idea or state of mind, a mood compounded equally of “the milky air of Dutch snow paintings” and “the smoke-pale sky of 1930s photographs of northern [English] towns”, of little red-roofed ports with “wooden houses clustering to the harbour under treeless slopes” and bleak, Audenesque frontiers where “the man who knows too many secrets can make his escape over the moors”; it is a region of “austere marvels” and “complex nostalgias”, all the more seductive for its severity.

Griggs’s etching is haunting in the first place because it seems to capture a quintessence of this kind of northness or wintriness; the stark light, the massy but strangely delicate architecture, the wonders of the snow. To account for its power in more formal terms you’d need to say something about the opposites it seems to hold in tension – movement and stillness, music and silence, immense weight and a certain airy upwardness. On the one hand, the picture seems replete with wintry stillness and a hushed calm; on the other, its composition has the relentless upward thrust of a Saturn V. It all begins with the humble ladder in the bottom of the frame, with its suggestion of a deep precipice below, then continues through the ascending tiers of architecture, which seem to become as flimsy as the frost before they pass into the sky itself. The effect is dizzying, disquieting. By a similar paradox, and one that is perhaps true of any picture that shows scenes of music-making, Griggs’s snow-bound carollers cast a strong spell of silence – outside the cold citadel of art, we will never hear what they are singing.

Of Griggs himself (1876-1938) I have discovered rather little. Although entirely self-taught, he served an apprenticeship in the Arts and Crafts movement and by the 1910s was widely considered the finest architectural draughtsman of his day. His best-known work was almost certainly his meticulous pen-and-ink drawings for the Macmillan Highways and Byways series, popular guidebooks that introduced a generation of Edwardian travellers to England’s built heritage. Later, in the 1920s, he moved away from the delineation of real buildings into the romantic, medievalist fantasy that reaches a peak in The Almonry – a masterpiece at once sumptuous and severe. I know little enough about the practical side of etching, but in terms of technique alone this is surely a prodigious work – what Davidson would term an “austere marvel”. The effects of light and texture here – snow on stone and wood and the air fizzing with frost – have a delicacy that you would associate with the more impressionistic kinds of brushwork, rather than with the bite of acid on metal. It’s not altogether strange that some recent critics have claimed for Griggs, obscure as he now is, a key position in English romantic art: this late work seems to look back through Pugin and Pre-Raphaelitism to the example of Samuel Palmer (whom Griggs idolized) and forward to the neo-romantics of the 1940s, most notably perhaps John Piper.

Mention of Pugin points to another salient fact about Griggs: he was a Catholic convert of a particular stripe, one whose love of the medieval took strength from a fierce sense of the ravages of secularism, materialism, and industrialism in his own time. It is almost as if, having painstakingly captured a vanishing England in his drawings for Highways and Byways, Griggs set out to preserve a richly idealized fantasy version – what Geoffrey Hill calls a “Platonic England” – in these late etchings. And looking again at The Almonry – is it fanciful to discern a sense of threat, of looming catastrophe? Judging by the costumes, we are somewhere in the early Tudor period and this cliff-top citadel of art, music, charity and true religion, will soon fall to the fury of the iconoclasts. Back to that ladder in the foreground, with that breach in the wall above it – doesn’t it look ominously like a siege ladder? Are we about to see the orcs of Mordor, or Modernity, come swarming up from the depths to overwhelm everything?

I never know what to think about this sort of romanticism, this invocation of a deep England beyond the profit and loss, beyond all sense and reason: it seems at once perilous and laughable and irresistible – “complex nostalgias”, indeed. It’s probably for these reasons that I’ve come to associate Griggs’s perfect little etching with a poem by Geoffrey Hill, our foremost analyst of these things – appropriately, it’s a section from his An Apology for the Revival of Christian Architecture in England (itself a title cribbed from Pugin):

THE HEREFORDSHIRE CAROL

So to celebrate that kingdom: it grows

greener in winter, essence of the year;

the apple-branches musty with green fur.

In the viridian darkness of its yews

it is an enclave of perpetual vows

broken in time. Its truth shows disrepair,

disfigured shrines, their stones of gossamer,

Old Moore’s astrology, all hallows,

the squire’s effigy bewigged with frost,

and hobnails cracking puddles before dawn.

In grange and cottage girls rise from their beds

by candlelight and mend their ruined braids.

Touched by the cry of the iconoclast,

how the rose-window blossoms with the sun!

There’s some staggering skill displayed in that work and to such remarkable effect. Thank you, JL, for the fascinating and beautifully-expressed appreciation. One wonders how much better known Griggs would be if he hadn’t worked in the twentieth century.

Thank you so much JL for, yet again, explaining something without making me feel like an arse. So glad you came back to the ladder – not the only puzzle in this fabulous work. The rupture in the wall? If recent, where did the hoards go? Everything looks calm thereabouts. If not recent, why are the ladders still there, and the gap unfilled? But best of all, the ‘big’ picture starts out of sight, down in the depths – and continues heavenward above…..

Griggs is a fascinating figure. His fantasy drawings seem stylistically very similar to the illustrations he did for the Highways and Byways series, but when you look a little more closely, there is very much this sense of something going on ‘off stage’ – not just the ladders and the rope, but these paths leading out of the frame to who knows where. And the architecture: the structure at the top looks like the buttressed east end of a cathedral or monastic church, but what then is the building at top left? These late images of Griggs are full of such mysteries. The juxtaposition with the Hill poem (one of my favourites) is suggestive. Hill’s vision has always struck me as very rural (squire, grange, cottage, etc), whereas Griggs’s picture is presumably part of a fortified town. But Hill’s poem has a similar sense of reaching back to an essence, but also evokes the threat, the sense of an ending. For Griggs himself the ending was not so happy. He made himself ill and poor building a very large house for himself in the Cotswolds, trying to create in stone a vision similar to those in his art. Unlike Pugin, he didn’t make it; like Pugin, he died too young.

Is the house still standing Philip?

An amazing post JL

Yes – the house is still there. It’s called Dover’s Court.

Wow! An amazing post indeed – and an amazing etching, which I’d never seen before. Only a peep of sky in all that vast picture space – no wonder it feels so unsettling…

Hear hear.