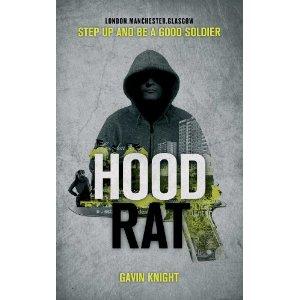

Hood Rat – Gavin Knight’s new book about Britain’s gang culture – makes for uncomfortable reading. We have a double-bill for you, kicking off with Jon Hotten’s review…

In 1991, David Simon published a book called Homicide: Life On The Killing Streets, that followed for a year the work of three murder squads – 18 men – in Baltimore. It was where Martin Amis got his often-ridiculed first line of Night Train: ‘I am a police’. Poor old Mart, besmirched again, for what David Simon had produced in Homicide was a work of forensic accuracy: if you wanted to know about murder in America – without having to get personally involved in one, obviously – here it was, laid out cold as the slab.

Amis championed Simon, whose immersive reporting had soon blossomed into the Homicide: Life On The Streets TV show, another book of year-long observation called The Corner, then The Wire and Treme and a position as America’s premier tell-it-like-it-is-down-there writer – without all the writerly frou-frou on top.

His success posed a question: why, with the Americanisation of British crime, had no-one done the same over here? Because we’ve got the ghettos and the no-go areas, we’ve got the underclass, and beyond that we’ve absorbed the sheen and glamour – ludicrously, for example, kids in London refer to the police as ‘Feds’.

What we don’t have, at least not yet, is the murder rate, although to judge by the most illuminating and alarming passage of Gavin Knight’s Hood Rat (Picador), we might get that soon, too:

Ten years ago, it was about the high-level drug dealers, older gang members brutally exploiting the younger ones. They taught them that all that counts is who can become the most brutal, the most violent, the most feared. Now the drug trade has become more fragmented, the violence is all the kids are left with. The older gang members who want to make money in organised crime, fraud or money-laundering can’t control them. They are too chaotic, too volatile. A twelve year old cannot wait to step up, shoot a general and get a reputation for himself. It’s like X-Factor.

Modern crime, it seems, is now too criminal to control itself. Knight’s book is in three parts, and three places. The first, and best, section is set in Manchester and features – zeitgiest-ly enough – a half Norwegian detective called Anders Svensson, and his long pursuit of two dangerous drug dealers, Merlin and Flow. Svensson’s greatest gift is patience, and he needs it. It’s apparent that the law is not on his side; it is, importantly, a neutral thing, as much an occupational hazard for him as it is for Merlin and Flow. The second section is set in London, and best demonstrates the generational shift. Pilgrim is the young ‘soldier’ who rises up through the gang and then goes to jail. When he gets out it’s like he’s aged in dog years, he’s some old granddad who’d once done something or other, something that means nothing to his replacement Troll, because Troll’s a real soldier, a child soldier from Somalia, and South London is like Las Vegas compared to Mogadishu.

The third part is in Glasgow, and focuses on Karyn McCluskey, head of intelligence at Strathclyde Police. Unlike London and Manchester, Glasgow’s violence remains resolutely old-school; ‘a typical murder involves a sixteen year old having a drink to steady his nerves, walking less than half a mile from his flat and being killed in a one-on-one arranged knife fight with some kids who live round the corner.’ The Americanisation here comes from the police. McCluskey hears about the work of David Kennedy, who has reduced gang crime in Boston by making its members confront the mothers of their victims, and brings Kennedy to Easterhouse. He has the same effect there.

Americans are less ambiguous about their cops and their laws and their prisons than we are. There is little appetite there, for example, for the kind of gangster memoirs with their glowering covers (‘I look what I am – A hard bastard’) that clog the true-crime shelves of Smiths. Yet their urban gang cultures are endlessly represented on television and in films. Hood Rat and Ronan Bennett’s recent Top Boy for Channel Four feel like the first few dispatches from the contemporary frontlines here. Both illuminate a place that only seems less alien when thought of in American terms.

Both have their faults. Top Boy, according to the estate kids that the Guardian asked to review it, didn’t have any police in it. And Knight fesses up in his foreword that ‘various names, nicknames, times dates and identifying personal characteristics have been changed and some characters created from composites of various people’, a statement that undermines some of what he writes (in the interests of full disclosure, it’s a mistake I made in a book long ago; it’s understandable, but it kneecaps what you’re trying to do). In the era of google, it’s a lot easier to find out which details are real and which are changed, too.

Hood Rat, though, contains truths that you may not like the look of, and to which there are no pat answers. Troll, the Somalian child soldier, got into the UK when his mother discovered that all they had to do was to claim to be Ethiopian. Somali gangs are now as ruthless as any out there. You might need to be David Simon to find the moral line on that one.

I enjoyed Top Boy, but as a gangster yarn. It didn’t quite ring true. But I’d like to hear JG’s take on urban gangs, and whether they’re now worse than they ever were.

I have it on good authority that a very good book on that subject is Geoffrey Pearson’s Hooligan:A history of respectable fears