In a post of extraordinary sweep and scope, James Hamilton looks at how the World Wars robbed Britain of its sense of future, symbolised by the eternally backward-facing game of football…

My last post about the relationship between the Great War and football generated a debate about the extent to which causualties robbed the game of skills and expertise, and it prompted me to look at FA Cup Final teams from 1900 to 1915 and their war losses. It was an outstandingly depressing task – so many of the dead players nearly made it to the end, but, like Wilfred Owen, ran out of luck in the final months before the armistice – but it became clear that the records were very incomplete. Although the proportion of dead among the FA Cup Finalists was approximately the norm when compared to the overall casualty rate, there were almost certainly other players who had died without the link to their sporting career not made. On the other hand, very few players actually stayed in the game for long – the average Edwardian footballing career lasted for seven seasons, and barely anyone stayed on in coaching or management. War death was not the only thing robbing football of its accumulated knowledge. It probably wasn’t even the major thing.

But the Great War did do something to football in England: it took away what was left of its future. I’ll try to explain what I mean by that.

In my last post, I described a view of the 1914-18 war as a kind of great stunning: a shock that created the urge to conserve, preserve and retreat into a kinder past. Something like this happened to football, but it’s complicated by other things.

Browse through bound volumes of the kind of magazine aimed at rich public schoolboys from the 1920s, and you’ll notice that the proportion of stories featuring football is surprisingly high. But as the decade progresses, the proportion declines, giving way to rugby. This reflected the changes on the ground. Those public schools without their own form of football were indeed moving over to rugby union, but it wasn’t out of snobbery: it was out of patriotism.

Football came out of the war with a mixed, damaged reputation. On the one hand, the football batallions had suffered mightily – Heart of Midlothian and Leyton Orient famously lost many sons. And there were many football stories from the front – balls being kicked ahead of charges into no-man’s land; matches with the enemy at the Christmas truce; football saving the sanity of prisoners of war. But at home, football had broken ranks with cricket and rugby by playing on for the whole of the 1914-15 season, and in doing so had attracted a world of ill-informed approbrium. Grounds were full of white feather men, it was asserted: sport was taking energy away from the vital struggle. (Grounds were full – that was true – but full of khaki uniforms.)

It is easy to understand how a school that has just put up its memorial board, loaded up with names that had remembered faces behind them for the masters and staff, might not want to go on with a game that had showed an ambivalent attitude to so much loss. Middle class amateur soccer went on and is still with us – civil service sides, teams from banks and law firms and the like – but the loss of the universities and public schools cut football out of the strange, Wodehousian path of interwar change and left it stranded in industrial cities that had almost run out of steam themselves.

It could even be argued that football had swung its attention round to the past as early as 1905. This was because football’s extraordinary Edwardian form came as such a surprise to itself. After 114,000 people turned up for the 1901 FA Cup Final, men began to ask themselves how on earth something so unexpected, so unplanned for, had happened so quickly. After all, the first generation of players, who had organised their sparse kickabouts in public parks and on open ground were themselves only entering middle age. “How did we get here?” became football’s question very early on, in the form of the 3-volume work Association Football and the Men Who Made It (I came across the original photographic prints for this at an Edinburgh book fair two years ago and failed to buy them…)

The question of where football was going wasn’t asked – where else was there to go, in 1905? Then, as now, the bubble was expected to burst at any minute, and the future was seen, as it is seen now, in terms of dark prognoses and moral judgements, not in plans and intentions.

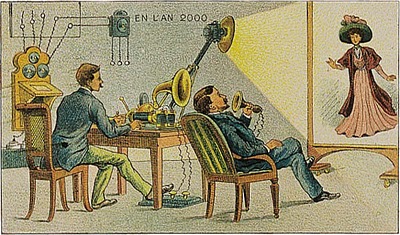

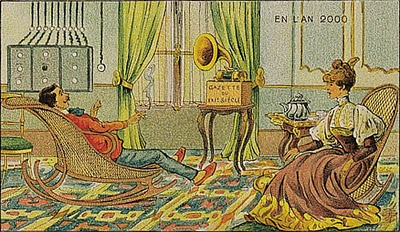

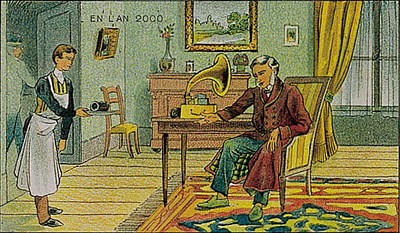

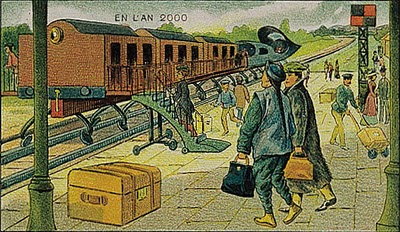

And anyway, futurology has never really chosen football (or cricket, for that matter, although it has been partial to athletics from time to time). Edwardian futurology focused on art and design, flight, radio, the motorcar and the prospect of television. But look at the illustrations accompanying this post, which date from 1906: the guesses people made about the future were often astonishingly accurate in concept, but quite wrong in aesthetics. The look of the future from 1906 is mired in a kind of eternal Edwardiana. They had electricity, but failed to see what it would do: take away smoke, create an ideal based around clean lines, cleanliness and simpler, more rational dress.

It’s notable that football’s essential aesthetic didn’t change after World War One. It remained a game of raucous crowds, baggy kit, huge boots, mud and flat caps from about 1901 all the way through to the early career of Bobby Charlton. It was different in Europe: football had a jazz age there, and the great interwar European photographers took the game to their hearts. It became a staple of art, advertising and propaganda. In South America, it became the focus for political ideas about national self-assertion.

This was partly, as we’ve seen, because football in England came to symbolise memories of the pre-1914 era, of the world whose values had been tested and proven in the trenches. The treachery of the 1914-15 season could be expunged, but only by pretending, on match day, that it was 1910 forever. In England, football was to be kept away from the great modernist aesthetic shift towards clean undecorated lines. Away from electricity, cleanliness, glass, whiteness, speed, sex.

With the coming of the Great Depression, all this was sealed in, as the great, swelling, cutting-edge industrial cities that had given birth to the modern game themselves became ageing backwaters, increasingly decrepit and incapable. J.B.Priestley thought the Depression had proven the entire industrial experience a destructive sham, brought upon the many to enrich the few, and saw many northern towns as places come to an end, populated by the abandoned and involuntarily useless.

Orwell had similar reflections, and fight back as the image-conscious burghers of a Gateshead or a Wigan might, nonetheless it remains the case that our industrial cities haven’t represented any kind of future ever since. Not as they once did, and football, their astonishing sporting child, only escaped the death embrace of the north through two accidents: the sheer tenacity of football institutions in this country, and the arrival in the nick of time of satellite television.

Lacking any real vision for its own future, football has allowed television to lead it into the modern age while it itself continues to gaze backwards, still seeing itself as some kind of repository for attitudes towards work, class and community. Never can there have been a British phenomenon so trashy, so plastic and yet so full of a past that was none of those things.

There’s reason to believe that there’ll never be another phenomenon of that kind. The two world wars were such extreme experiences for the entire British population – the first history that really, inescapably caught simply everyone up in it and changed everything for them – that the old history of Drake and Nelson lost its explanatory power. Now the stories that explain how the British became the British are all from 1914-18 and 1939-45. We’ve become a people living in the eternal aftermath of those events, and football – more stable than music, more universal than art – has, in its unsatisfactory, backward-facing foot-dragging way, served as the perfect symbol of the unsatisfactory, backward-facing, foot-dragging British experience as time leads us unwillingly away from our last great days.

It’s a wonder to see the historical imagination at full-stretch, James, and that was something of a dive-header into the back of the net! Occasionally, you come a across a historical insight that reconfigures the way you think of the past and therefore the present. That was one of them. It needs much pondering on.

Great post, but then when has James Hamilton produced anything remotely duff. Gaw’s comment captures my feelings wonderfully well.

It is very surprising that professional football careers lasted, on average, only seven years. Was that because most players had come from poor backgrounds and poor nutrition resulting in inherent physical weakness and rapid deterioration in their twenties? Was it because they turned professional later (early to mid twenties)? Was their lack of progress into management determined by class and education?

You write about the backward-facing tendancy of Britain and its football. I find it interesting that in the early 1900s the great C B Fry was also looking back, and at the same time contemplating a grim aspect of football’s future. He was, of course, among many other things, a notable amateur footballer and had played in the 1902 Cup Final, but now he was lamenting the development of a fierce competitiveness among clubs and supporters: ‘A magnificently fought-out game, ending in a goalless draw, will leave the crowd sullen and morose. They wend their way home from the ground with black looks, cursing the bad luck of the home side. An undeserved victory for the home team will leave no regrets. There is no sportsmanship in a football crowd…..Partisanship has dulled the idea of sport and warped its moral sense.’ That final sentence could be applied to a lot we witness today.

I wonder just how significant a factor the continuation of football throughout the 1914/15 season was in the reduction in the appeal of the game to the upper classes in the mid/late 1920s. At that distance from the first year of the War, would it have been diluted to a marked extent?

The post raises so many interesting issues. I really must go and ponder.

As I said to James off-blog, there’s enough in here for many posts.

When (very soon) there is a European Super League, will we already be looking back nostalgically at today’s relatively lowly paid and innocent Premiership…?

No.

I suppose it depends on your definition of ‘we’. But Man Utd ‘fans’ (which description seems to apply to approx half the world’s population), will certainly look back on Sr’Alex as the hero of a Golden Age, if he ever happens to finally retire.

Never underestimate people’s ability to feel nostalgic about things that were mostly rubbish.

My aunt’s father Tom Davis played for Oldham in the 30s, his career in England seems to fit the 7 year average. For any level of success in football I think you have to be tough and ruthless, which apparently he was. Not sure if there was ever an age of innocence!

The reasons behind the average seven year career intrigue me. I therefore googled it and look where it took me……….. more fascinating commentary on Edwardian football

http://mtmg.wordpress.com/2010/03/02/sex-and-the-edwardian-footballer/