From Fu Manchu to Fred Astaire this week, as Jonathon Green continues his slang tour of London by venturing into the East End’s Chinatown and the heady scents of opium and white slavery …

It’s not so much the slang coinage, because Limehouse as such didn’t generate any (other than the rhyming slang Limehouse cut = gut), but the place had to be permeated with it. It was docklands: rough, tough and rampageous. Jack, pockets briefly heavy with a voyage’s pay, reeling his way to the dubious pleasures of the Ratcliff Highway and the whores on the badger game and the crimps with their hocussed drinks, the slop shops (which sold clothes) and the taverns (which sold slops). This is not standard English country, they don’t talk proper here, though once, like most parts of the East End, it was smart and the merchants built their houses within view of the vessels that made them rich, lying upriver from Limehouse Hole. It took its name from lime-kilns, first recorded in 1356; they served local potteries and the potteries served the ships. The docks proper were there by 1500.

Docks, well there’s a certain romance – all that down to the sea again, apes and spices from all points east and west, creaking canvas, nine-tailed cats and salty tars – or there might have been before docks became Docklands and Canary Wharf and little boxes made of city boys. I prefer my Limehouse fictional. I’m not alone. In 1916 Thomas Burke wrote Limehouse Nights, a disappointingly goody-goody collection of tales even if the stories had titles like ‘Beryl the Croucher’ and ‘The Chink and the Child’ (in 1919 Richard Barthlemess was one and Lilian Gish the other in D.W. Griffth’s Broken Blossoms aka The Yellow Man and the Girl ). The London libraries banned it at first because of alleged immorality which meant that Chinese men chased and sometimes caught white women. The readers weren’t worried: it was what was wanted: poverty, proles, drunken lascars, a touch of Bret Harte’s ‘heathen Chinee’, a smear of ‘yellow peril’, and white women, both as good or no better than they should be. The heady scent of white slavery.

And that other heady scent: opium. It wasn’t new – De Quincey had written it up in his Confessions in 1822 and Coleridge had likely been stoned, if only on opium’s tincture laudanum, when he wrote ‘Kubla Khan’, and it pops up in Wilkie Collins’ Moonstone in 1868 – but they had been … literary gents. And white too. Presumably they’d had friends in the trade. One couldn’t see the Romantics scoring. John Chinaman, now that was … another story. Several. Dickens set it off in Edwin Drood, the unfinished novel of 1870 which began as choirmaster John Jasper leaves the Limehouse den run by Princess Puffer (who Dickensians, hot to solve the Mystery, suggest might have been his sister, even if Luke Fildes has her looking pretty oriental). The Chinese had worked the boats as lascars (a mis-reading of Urdu lashkar, army) and coolies (a possible mix of Gujarati Koli, a manual labourer caste and Turkish qul, a slave) and started staying. Some must have seen the East End as a better place to live than ‘tween-decks, others were perhaps shanghaied (which technically referred to the Chinese entrepot, but could happen anywhere if the bludgeon or Mickey Finn was properly applied) and missed their passage home. By the 1860s there was sufficient community for Dickens’ dreams. Chinese equalled opium – thanks to the British who had taken it there from India – or it did in the US and in France, and how could the world’s greatest city not offer what Yanks and Frogs had in abundance. So Dickens, and Burke and newspaper scare stories and the black mud. Even if real-life records seem to have overlooked it. Maybe there was a subconscious throwback to the 16th century when Humphrey Gilbert, a local, brought friends to practice alchemy at his Society of the New Art. No matter. Art trumps life. In 1910 the Canova Novelty Company who manufactured coin-in-the-slot machines released their latest: ‘Limehouse Nights Raid on an Opium Den’. No surviving machines but their others offered the self-explanatory ‘American Execution’ and ‘Madame Guillotine’ and ‘The Drunkards Dream’ (which was of terror in a graveyard) and wouldn’t you have paid your penny.

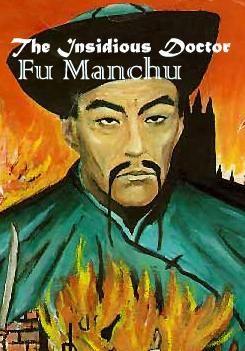

‘Imagine a person, tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, … one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present … Imagine that awful being, and you have a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man.’ The Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu. Graduate of Heidelberg, the Sorbonne and Edinburgh (a contemporary perhaps of Conan Doyle?). What a master criminal, what a slit-eyed devil from hell, what a moustache. If pursuer Nayland-Smith is Holmes, then Fu (or is it Manchu?) is surely Moriarty (even if Richard Greene, aka Robin Hood, played him in 1968 and Peter Sellers in 1980). And what of his daughter, the ‘seductively lovely’ Kâramanèh: is she not Bulldog Drummond’s devil-woman Irma Petersen in embryo? And every femme fatale that followed. Though Drummond never laid hands on Irma, preferring the prissy Mary who couldn’t even deal with a tarantula when it comes through the post (a tip: beat it to death with the poker). Nayland’s Watsonian sidekick Petrie actually married the Asian babe. The Doctor’s creator was ex-music hall gag writer Arthur Sarsfield Ward (1883-1959) who wrote as Sax Rohmer and dressed, at least on occasion, as his money-spinner. He had other characters – Morris Klaw, Gaston Max, The Crime Magnet – but who remembers.

‘Imagine a person, tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, … one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present … Imagine that awful being, and you have a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man.’ The Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu. Graduate of Heidelberg, the Sorbonne and Edinburgh (a contemporary perhaps of Conan Doyle?). What a master criminal, what a slit-eyed devil from hell, what a moustache. If pursuer Nayland-Smith is Holmes, then Fu (or is it Manchu?) is surely Moriarty (even if Richard Greene, aka Robin Hood, played him in 1968 and Peter Sellers in 1980). And what of his daughter, the ‘seductively lovely’ Kâramanèh: is she not Bulldog Drummond’s devil-woman Irma Petersen in embryo? And every femme fatale that followed. Though Drummond never laid hands on Irma, preferring the prissy Mary who couldn’t even deal with a tarantula when it comes through the post (a tip: beat it to death with the poker). Nayland’s Watsonian sidekick Petrie actually married the Asian babe. The Doctor’s creator was ex-music hall gag writer Arthur Sarsfield Ward (1883-1959) who wrote as Sax Rohmer and dressed, at least on occasion, as his money-spinner. He had other characters – Morris Klaw, Gaston Max, The Crime Magnet – but who remembers.

Fantasy Limehouse lived on. Jack Buchanan and Gertrude Laurence, suitably ‘yellowed-up’ if such a concoction works, sang ‘Limehouse Blues’ in 1921; Fred Astaire reprised it in 1946, bringing a never-was East End to the Ziegfeld Follies. The name served for a George Raft quota quickie in 1934. Chinatown hard man relocates in London; Anna May Wong plays the girl. Peter Ackroyd’s Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem appeared in 1995, set a century earlier. But Leno, although he played Widow Twankey, was no lascar, and the Golem was a figment of a Prague rabbi’s imagination, not a pipe of yen-shee.

Not much slang then. Apologies. But this is fantasy-land. My advice? Make it up as you go along. Everyone else did.

Marvellous stuff as ever, JG.

On the subject of Edwin Drood – can anyone recommend it? I’ve not read it, having been put off by the unfinished element, but then again Dickensian endings aren’t essential… is it worth the effort?

Not sure I really can. As you say, the unfinishedness is terrific, and ultimately off-putting. You’re maybe right about CD’s endings, but there is so little of Drood completed that one scarcely gets a beginning. Stick with Our Mutual Friend and Bleak House. Dickens at his glorious peak (if you you can stomach the Esther Summerson bits in BH).

Those are by far my favourite Dickenses, both worth wading through the sickly stuff, though Our Mutual Friend has very little. I’m gestating a post on OMF as it happens.

I think these hugely engaging London slang posts would make fantastic short radio pieces – spoken word with some illustrative sounds perhaps, some on location. Any enterprising radio programme commissioners out there?

I agree, these posts are all super atmospheric and would make terrific radio! I recently read an old pelican paperback called The Victorian Underworld by Kellow Chesney that has quite a fair bit on opium and the chinese. Very interesting (the opium, not the book, which was disappointingly unsalacious)

Chesney is essentially a paraphrase of Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor (1861). And the original is far superior.

Thank you for the radio thought. The Beeb used to love me, but not for some years.