Jonathon Green introduces his favourite collector of slang (and an ancestor of The Dabbler’s very own Jon Hotten), John Camden Hotten…

SLANG represents that evanescent, vulgar language, ever changing with fashion and taste,…spoken by persons in every grade of life, rich and poor, honest and dishonest…Slang is indulged in from a desire to appear familiar with life, gaiety, town-humour and with the transient nick names and street jokes of the day….SLANG is the language of street humour, of fast, high and low life…Slang is as old as speech and the congregating together of people in cities. It is the result of crowding, and excitement, and artificial life. It is often full of the most pungent satire, and is always to the point. Without point Slang has no raison d’etre.

Thus John Camden Hotten, author of ‘A London Antiquary’ of Modern Slang, Cant, and Vulgar Words. Published in 1859 it became The Slang Dictionary in 1864 and was still being revised at his death. For me, this is slang’s best definition, and Hotten my favourite collector.

John William Hotten (‘Camden’ came later) was born in St John’s Square, Clerkenwell (Johnson had worked there at the Gentleman’s Magazine), on 12 September, 1832. At fourteen he was apprenticed to a Chancery Lane bookseller. During that employment he was supposedly thumped with a large quarto edition by the historian Macaulay, irritated by the young man’s failure to make change sufficiently speedily. In 1848 he and his brother sailed for America, a trip that, according to Mark Twain, was necessitated by Hotten’s having been caught out selling his master’s stock for his own profit. First stop was ‘the West India Islands, which was to be the field for a Robinson Crusoe scheme of adventure’ with the Hottens narrowly avoiding shipwreck and landing with ‘two chests of books, and two chests of tools and fire-locks—the latter we thought necessary to build and protect there a wooden house or castle we decided upon building.’ The castaway life lasted six weeks before the brothers moved on to America and separated. He worked as a miner then freelance writer, and in 1856 re-emerged in London and opened a bookshop at 151b Piccadilly. With success he expanded at 74-75.

Contemporaries judged him ‘fast’ and definitely modern. A workaholic. Writing his obituary for the Bookseller, Hotten’s friend the bibliographer Richard Herne Shepherd laid out a day that lasted, with the briefest of lunch breaks, from ten in the morning to nine at night. And after that work, or even an aspirant author, would be taken home. There was, Shepherd suggested, ‘something heroic in all this, even if of a degenerate modern kind’.

He published editions of Bret Harte, Oliver Wendell Holmes, James Russell Lowell and Artemus Ward. He offered C.G. Leland’s dialect poem ‘Hans Breitmann’s Party’. He wrote biographies of Thackeray, Dickens and H.M. Stanley and edited collections of Christmas carols. The business faltered then took off: by his death he had published 446 titles, nearly 1.5 million books.

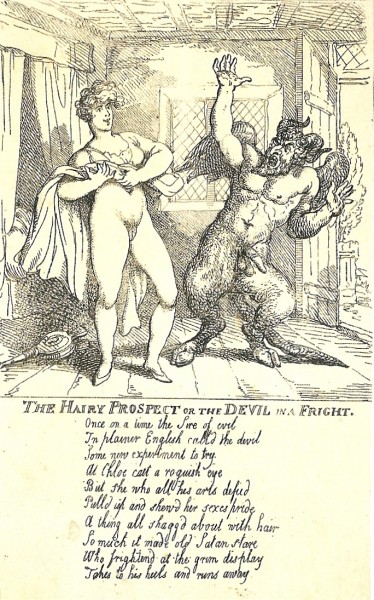

And there was the other business. His success, or at least a good deal of his income, rested on his exploitation of what Partridge called ‘the by-ways’ of Victorian life. Porn. Hotten called it his ‘flower garden’, and in it bloomed such titles as The History of the Rod, the illustrator Thomas Rowlandson’s Pretty Little Games (a series of ten erotic plates) and The Romance of Chastisement. His private library of erotic literature was extensive. In 1866 he also published A.C. Swinburne’s Poems and Ballads which, while hardly obscene, had been rejected by its original publisher Moxon who feared a prosecution under the recently passed Obscene Publications of Act of 1857. Swinburne, who appreciated flagellant pornography himself, helped Hotten with The Romance of the Rod.

Hotten died on 14 June, 1873, either of ‘brain fever’ or, as some claimed, of a surfeit of pork chops. Swinburne, less than grateful, noted that, ‘When I heard that [Hotten] had died of a surfeit of porkchops, I observed that this was a serious argument against my friend Richard Burton’s views on cannibalism as a wholesome and natural method of diet.’ An anecdote, featuring either the poet-sociologist George R. Sims or the American Ambrose Bierce (later author of The Devil’s Dictionary), tells how a writer appeared at the bookshop brandishing a cheque that had bounced. He commenced shouting only to discover that those present thought he was an undertaker, and informed him that the publisher had just died. It was definitely Sims who is credited with the last word: ‘Hotten: rotten, forgotten’.

Hotten is not forgotten. Modern Slang was a hit: it sold out quickly, was rapidly reprinted and ran to several editions. It remained the authoritative work for nearly forty years. Hotten made substantial advances in every aspect of his task. For the first time ever, a slang dictionary offered an overview of its subject. Hotten prefaced his work with a ‘History of Cant, or the Secret Language of Vagabonds’ and a ‘Short History of Slang, or the Vulgar Language of Fast Life’. His histories of both speech varieties – the differences between which he was the first to explain – are extensive, if not always conclusive. A glance at the running heads gives a flavour: ‘Vulgar Words from the Gypsy’, ‘The Inventor of Canting Not Hanged’, ‘Swift and Arbuthnot Fond of Slang’, ‘The Poor Foreigners Perplexity’.

He has lists of rhyming slang and of back-slang, both prefaced by a brief history and discussion. There is, again for the first time ever, a Bibliography of Slang and Cant, listing some 120 titles, plus his own critical comments on each. Hotten stresses that above all this is a dictionary of ‘modern Slang – a list of colloquial words and phrases in present use – whether of ancient or modern formation’. He opts to exclude ‘filthy and obscene words’ although he acknowledges their prevalence in street-talk and deals at length with oaths. He touches on jargon, without describing it as such, and thus deals with the terminology of the beau monde, politics, the army and navy, both high and low church, the law, literature, the universities and the theatre. He has a list of slang terms for money, one of oaths, one for drunkenness and deals with the language of shopkeepers and workmen. It is, for a relatively condensed work, a little over 300 pages in all, a great achievement.

Jonathan, did Hotten have anything to do with Dugdale and the industry behind doors in Holywell Street?

They certainly overlapped, although Dugdale was well established at least two decades before Hotten opened his shop. Judging by the absence of Dugdale from the biographical essay on Hotten written in 2000 by Simon Eliot, who is also responsible for the current New DNB entry, there is no actual record of their doing business, or none that has emerged. Given the nature of the material, who knows what may have gone on. That said, Eliot sees Hotten’s porn output as a forerunner of such (relatively) up-market dirty books as those that Maurice Girodias put out under the Olympia Press imprint in the 1950s, rather than as the fully-fledged, Holywell Street filth that Dugdale published. This is debatable. To which level of the market, for instance, did Hetten’s 1872 Library Illustrative of Social Progress (including such titles as ‘Lady Bumtickler’s Revels’, ‘A Treatise of the Use of Flogging in Venereal Affairs’, and ‘Madame Birchini’s Dance Sublime of Flagellation’) belong?

Thank you! (I’d put the Library Illustrative alongside the Blue Books, but that’s me). I’d suspected that Dugdale was, well, beyond the pale (I suspect him of more than one attempted murders in connection with my own research, but without the evidence etc) but it’s good to have it borne out: Hotten’s apparent emphasis on flogging, as opposed to Dugdale’s on the – otherwise vanilla, ugh – exploitation of lower class women is perhaps telling.

fascinating, and I’ve just googled Holywell St and found that it no longer exists which I didn’t know

Indeed. For those who haven’t googled, it is now, to be very general, Aldwych; or more precisely it’s buried under the BBC World Service and adjacent buildings.

What is it about the British and flagellation? Is it a particularly British proclivity in fact?

Yes, Brit: it’s like the Germans and coprophilia.

Mr JG – quite superb. You have doen the man proud. I shall print this out and give it to my dad, whose name is George John Camden Hotten [ a family legend had it that the first male child with the name ‘Camden’ would come into money – he was, and he didn’t…]

And when I go [not bloody yet, obviously…] I hope it’s of a surfeit of pork chops too.

why was it that people in those days managed to die from surfeits of eating (lampreys et al..)

Does anyone these days die from a surfeit of eating? and what exactly is the medical cause?

After some googlage, I’ve found out that the Duchess of Queensbery died from a surfeit of cherries, as did quite a few others it would seem. King John may have died from a surfeit of peaches in 1216, Pope Martin IV died of a surfeit of eels – and Duc d’Escars died of a surfeit of a dish called Truffes a la purée d’ortolans invented by Louis VIII. They cooked the dish together, enough for ten people, then sat and ate it between them. ‘The Duc awoke in the middle of the night indisposed, and forthwith died of a surfeit.’

How many pork chops constitute a surfeit?

And how many ortolans:

‘You catch the ortolan with a net spread up in the forest canopy. Take it alive. Take it home. Poke out its eyes and put it in a small cage. Force-feed it oats and millet and figs until it has swollen to four times its normal size. Drown it in brandy. Roast it whole, in an oven at high heat, for six to eight minutes. Bring it to the table. Place a cloth—a napkin will do—over your head to hide your cruelty from the sight of God. Put the whole bird into your mouth, with only the beak protruding from your lips. Bite. Put the beak on your plate and begin chewing, gently. You will taste three things: First, the sweetness of the flesh and fat. This is God. Then, the bitterness of the guts will begin to overwhelm you. This is the suffering of Jesus. Finally, as your teeth break the small, delicate bones and they begin to lacerate your gums, you will taste the salt of your own blood, mingling with the richness of the fat and the bitterness of the organs. This is the Holy Spirit, the mystery of the Trinity—three united as one. It is cruel. And beautiful.’

Brendan Kiley, a US writer, at http://www.thestranger.com

Jonathon – you’ve just reminded me – on the subject of truly macabre cookery, since once chancing upon this account within the pages of a dusty old book in an antiquarian bookshop, I have always carried in my head the memory of this hideous recipe:

A Goose roasted alive – from Magia Naturalis:

A Goose roasted alive. A little before our times, a Goose was wont to be brought to the table of the King of Arragon, that was roasted alive, as I have heard by old men of credit. And when I went to try it, my company were so hasty, that we ate him up before he was quite roasted. He was alive, and the upper part of him, on the outside, was excellent well roasted. The rule to do it is thus. Take a Duck, or a Goose, or some such lusty creature, but he Goose is best for this purpose. Pull all the Feathers from his body, leaving his head and his neck. Then make a fire round about him, not too narrow, lest the smoke choke him, or the fire should roast him too soon. Not too wide, lest he escape unroasted. Inside set everywhere little pots full of water, and put Salt and Meum to them. Let the Goose be smeared all over with Suet, and well Larded, that he may be the better meat, and roast the better. Put the fire about, but make not too much haste. When he begins to roast, he will walk about, and cannot get forth, for the fire stops him. When he is weary, he quenches his thirst by drinking the water, by cooling his heart, and the rest of his internal parts. The force of the Medicament loosens and cleans his belly, so that he grows empty. And when he his very hot, it roasts his inner parts. Continually moisten his head and heart with a Sponge. But when you see him run mad up and down, and to stumble (his heart then wants moisture), wherefore you take him away, and set him on the table to your guests, who will cry as you pull off his parts. And you shall eat him up before he is dead.

Thank you for sharing.

I believe Mitterand ate a couple once he knew his death was imminent, napkin on head and all.

This is a piece on Mitterand’s final meal, from Esquire (May 1998): http://www.esquire.com/features/The-Last-Meal-0598