Martin Morgan is a Welsh blogger, exiled to England for his love of fine living. His main achievements are founding the Cymru Rouge hyper-nationalist fraction and coining the word “chwerthfawr”.

Andrew Rawnsley, in his excellent book on New Labour ,”Servants of the People”, refers to Wales as Scotland’s “ugly sister”. This is a strange comparison, as it implies that there are two Waleses and that we both gang up with wicked Stepmother England to stop the Scots going to the Independence Ball. Now we find the North Britons as tiresome as the next man, but hardly devote our time to doing them down.

Rawnsley has a point about our dowdy reputation, though. The Scots have a certain rugged, Connery glamour, while the Irish (Catholics only) are a protected species in Hollywood and among the liberal English. We Welsh, on the other six-fingered hand, are just grateful when anyone bothers to insult us.

Why are we always facing relegation from the Celtic Premier League to hop around with the Manxmen? It’s partly a question of presentation. The Irish won respect by bombing their critics, a tactic other religious maniacs have since taken up with relish. The Scots prefer to nest in HM Government like glowering russet cuckoos.

But underneath these efforts skulks a more sordid truth. The English admire our Gaelic neighbours with a clear conscience, as one visit to the peaty, midge-grey murk of those outlands convinces them that Scotland and Ireland may need controlling but certainly not settling, at least not by Englishmen.

Wales, on the other hand, is a pleasant land with its Gulf Stream, sandy beaches and custard slices. You can also get there without crossing the Irish Sea or the Geordies. The English want our lovely Wales, and we just get in the way.

So Wales needs to study how other dumpy countries won international praise. Once the United Nations and liberal press are on our side, public opinion and social-media campaigns will fall in line.

I’ve decided that our soft power of choice should be literature. Not the worthy stuff you pretend to read to impress girls on Facebook, but the real, middlebrow paperbacks and film scripts that make the trade go round.

Let us examine some case studies. Afghanistan, Portugal, Latin America, Central Asia and Iraq are at best mediocre places with smug or grisly neighbours who just won’t leave them alone. So far, so Welsh. How come they’re suddenly modish? Through middlebrow literature, that’s how.

The Afghans know that Pakistan is a scarier place, and resent the bad press they get because of the Taliban and their radical education and public-order policies. But now Khaled Hosseini’s novels “The Kite Runner” and “A Thousand Splendid Suns” have restored Afghanistan to its rightful place as a land of distant wonder. Mr Hosseini’s books are as splendid as any number of suns, and their dreamy titles and Hollywood treatment have persuaded the non-enlisted public that Afghans are a good thing and worth fighting for.

Portugal is an awkward place tucked under Spain’s armpit like a dubious legal brief. The language is Spanish on ten pints a night, and those anticlimactic bullfights and undernourished guitars impress no one. Then along came Richard Zimler with “The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon”, deftly passing Portugal the thirteen-petalled rose of Sephardic mysticism that Catholic Spain had tried to crush. Suddenly José Saramago wins the Nobel Prize, and chooses not to ask many questions why.

To children of the 1960s like me Latin America means fugitive Nazis, and unshaven army officers shoving cattle prods up some student’s arse. Magical realism changed all that, allowing García Márquez, Isabel Allende and literary piggybacker Louis de Bernières to conjure endearing Andean dynasties in an alliterative world of safely defunct indigenous wisdom.

Nothing much has emerged from Central Asia in a long time – not even the Oxus and Jaxartes rivers, thanks to Soviet irrigation schemes. I lived there for three years, amid the mutton kebabs and round-corner spitting, and thoroughly enjoyed myself. But it took Amin Maalouf’s “Samarkand” to lend the region Omar Khayyam’s allure and the Titanic’s fatal charm. Queues of tearful Peace Corps volunteers at Tashkent Airport, each clutching a copy as they haggled with Uzbek customs men for the return of their underwear, confirmed the initial success of this unwitting campaign.

And Iraq. Well, it was hardly “One Thousand and One Nights”, but Michael Moore’s image of kite-flying Baathist Baghdad in “Fahrenheit 9/11” convinced millions of cinema-goers that Iraqis were better off being Saddamised than invaded.

Welsh literature, whether in Welsh or English, has not yet mastered the art of public relations in print. It offers the following unhelpful genres:

How Green Was My Lung: grimy tales of coal/slate/cockle mining, pithead medical misery and steel-bending. See Kate Roberts’s “Traed Mewn Cyffion”, the work of T. Rowland Hughes, and almost all novels in English prior to 1980.

Bloody English: Englishmen came and ruined our valley, village or country. Nonconformism is the answer. See the works of Islwyn Ffowc Elis, and almost all novels in either language prior to 1980 not covered by the above.

Bloody Welsh: The Welsh ruin their own valley, village or country. Nonconformism is the result. See the works of Caradog Evans, RS Thomas and the remaining novels in English prior to 1980.

Straight is the Gate: The torment of being a Calvinist-Methodist cleric or – worse – some sort of Quaker in the perpetual drizzle of 19th century Meirioneth. See the works of Daniel Owen, Marion Eames and much of S4C’s 1980s TV adaptations.

Unread Modernism: Saunders Lewis’s “Monica”, “Un Nos Ola Leuad”, anything by Robin Llywelyn. It’s never clear what, if anything, is going on, then everyone dies.

Cool Cymru: Ingratiating attempts to brand urban South Wales as a sort of Newcastle with worse toilets. See the crime novels of John Williams and the film “Twin Town”.

These artistic efforts are hardly likely to win us the applause and therefore unthinking support of people who go on holiday but call themselves “travellers”.

We do have some native models. John Cowper Powys’s “Owen Glendower” goes on a bit, but sets out a very filmable mythos. Alan Warner’s “The Owl Service” does the same with actual mythology, and adds the magical ingredient of magic. They both fail, however, by falling into the highbrow and children’s literature categories. The sins of the former are evident, and that latter could burden Wales with a Harry Potter following of infantile 40-somethings. Welsh spelling might also entice adepts of all things Elvish.

The foreign novels I mentioned have characteristics that Wales must adopt if its literature is to establish airport hegemony:

1. The author should not be totally and utterly Welsh. Khaled Hosseini is Afghan-American, Richard Zimler is an American resident in Portugal, Amin Maalouf is Franco-Lebanese, and Louis de Bernières is Norman-English. This cushions the reader from contact with something truly strange, like a book translated from Pashto or Arabic, until they are hopelessly hooked on the country in question.

2. In related news, the novel must be in English. Celts are only acceptable when not too alarmingly alien. Think of the way the interplanetary petitioners conceal their appearance in “Galaxy Quest”, a film that a future Welsh foreign service should use in training its diplomats.

3. “De la musique avant toute chose”. Our model authors’ names sound musical, and so should the title of the novel, its protagonists and locations. The prose must be prosaic, but the proper nouns must soar. Think Parnassian: Elroy Flecker’s “Golden Journey to Samarkand”, WJ Turner’s “Romance” and Flaubert’s “Salambô”.

4. The plot must include the following ingredients: an object of desire, the place where it is hidden, and a sanitised myth to bear the reader along and persuade him that he’s learning something on the way. These must, like the names, balance a sense of wonder with an absence of friction. So coracles and love-spoons might work, while the Welsh Not would not. Harps are borderline.

5. Locations are only good when they’re green. Underwater myths have real appeal, especially lakes full of serpents, swords and silent cities, but only if they were drowned by angry gods and not the Birmingham or Liverpool Corporation Water Departments.

6. The protagonists must include a smart chick and a spiritual elder. Please note: whatever else happens, these two must not have sex with one another.

Armed with these sturdy tools, a writer can hew pure literary slate from the mountain of meaning. I heard that scores of copies of “The Da Vinci Code” was strewn across a hillside when a passenger plane crashed some years ago, just as “Samarkand” will ever be cupped in the hands of the ghosts of Tashkent airport. I like to think that one day “The Bridles of Senghenydd” will litter the lay-bys of Gwent when Newport-bound coaches pause to let our European visitors admire the view. “Et tout le reste est littérature”.

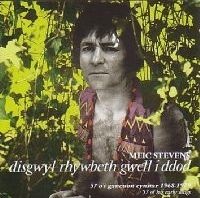

You’d think the classic Welsh chest rug as displayed by Meic on the cover above would be sufficient to win over international readers. It worked for Tom.

It worked for the Welsh wizard Giggsy. The only way was up, up and up again after scoring that semi-final replay goal against Arsenal in 1999, then throwing off his shirt and revealing something so stupendously black and bushy that grown men gasped and women everywhere offered to dubbin-up his size 8s.

a thoroughly amusing and absorbing read! And I agree that there’s definately room for some quality welsh lit – I don’t think I’ve ever read anything at all about Wales, except Philip Larkin’s ‘Sunny Prestatyn’…

Sterling stuff Martin, if you will pardon the pun and Wales is indeed England’s Helmand Province. You Welsh invented the finest star wars defence system outside of Ronnie Regan’s napper, the Welsh language roadsigns, now copied by Johnnie foreigners everywhere.

We Geordies of course have our own highly effective deterrents, an unfathomable language and the wimmen.

The father of an old friend whose life was ruled by stereotyping used to say “nivver wark to wark with a Welshman”, when asked why he would reply “always whining” an attribute he himself was well endowed with.

In translation..”wark to wark” mens roughly….”walk to work.”

Inspiring. If I were Welsh I would start this novel RIGHT NOW.

Excellent, Martin, that’ll get them flocking over the Severn bridge (until they realise how much if costs to get into Wales, that is). Re. “The prose must be prosaic, but the proper nouns must soar”, are we to assume dialogue of ‘singsong’ lyricism or salt-of-the-Valleys realism?

Martpol – I’m delighted to have visited your Ukrainian cousin Mariupol on at least one occasion. Anyway, what I mean by the “prose must be prosaic, but the proper nouns must soar” is that the novel must be written in International Bestseller English (flick through any Dan Brown for a flavour, if you can detect any), spiced with our native vowel-free names. “Gwrtheyrn watched Gwenhywfar braid her hair with cockleshells in the dying, sacrificial sunset at Senghenydd”. That sort of thing. Valleys realism comes under “How Green Was My Lung”, and is streng verboten as we used to say in Dolgellau during the war.

You are all too kind! I would urge you to start writing your own Welsh novels, whether you be Welsh or not. We are always happy to share the credit for other people’s work.

A question Martin, if you haven’t already sat down to watch leekyvision.

You know the Welsh Eyestead Ford, is it like, an S-Max with a coal fired engine.

Welsh TV sets are steam-powered, our cars run on cooking oil. Our preferred stolen sets of wheels are the “Rhyd yr Ŵyl” (Ford Fiesta).

If I come up with some sort of bodice-ripping Lloyd-George knew-my-sisters-and-even-may-have-had-a-go-at-my-brother shagfest, does that count as WelshLit?

It does now, Ron. I’ve not really explored the surgical-stocking-ripping subgenre yet.

You haven’t lived my friend until you have tiptoed your way around some of the colostomy bag stuff that’s out there.

Hilarious.

Wasn’t the fellow in Kingsley Amis’s The Old Devils practicing exactly that? I offer you from the US a name for the genre: Eisteddfrod.

Oddly enough, when I try to come up with a Welsh novel, I think of The Tour of Humphrey Clinker, written by a Scot.

Amis is a writer who got the Welsh just right, which is fair enough as he taught and is fondly remembered at my old college, Swansea. Lucky Jim, That Uncertain Feeling and The Old Devils do the trick for our priapic shiftiness.