Philip Wilkinson is the author of over 40 books, including The English Buildings Book, and most recently The High Street, written in conjunction with the BBC TV series. Happily for us, he’s also the curator of the English Buildings Blog, a firm favorite here at The Dabbler. In this new series of posts, Philip talks us through some overlooked architectural gems…

Of all the retailers of the interwar period, few were as good at using decoration to inspire us and to take us to other places as W H Smith. If this at first seems strange – after all Smith’s, as newsvendors, had a vested interest in presenting the daily harsh realities of life – we should also bear in mind that Smith’s, then as now, also sold maps, postcards, and books. And from the Edwardian period to the 1960s at least, their stock, and the way it was promoted, was highly literary. I can just remember the ornate Smith’s shop front of my childhood home town, which was emblazoned with a quotation from Wordsworth: ‘Dreams, Books are each a World and Books we know are a substantial World both pure and good.’ Others had Shakespeare: ‘Come and take choice of all my library and so beguile thy sorrow.’

There could be pictures as well as words on the fronts of these shops, and pictorial tiles were sometimes used. A pair of wonderful tiled panels surviving outside the Great Malvern branch of W H Smith’s shows how imaginative these tiles could be. The shop front is recessed slightly from the building line, leaving two narrow strips, like exterior window reveals, at right-angles to the street. The two tiled panels are set at the top of these strips, and so are rather easy to ignore. How typical of the painstaking design of the time that such trouble should be taken with these easily overlooked spaces.

And what amazing images their ceramic artist produced. The car rattling along in the ‘Road maps’ panel conjures up all the optimism of the open road in the 1920s. There’s little hint of where the scene might be set (it could just as well be France as Worcestershire), but the sun is out and the road, we feel, is empty ahead. The driver has read his road map and he’s opened the throttle.

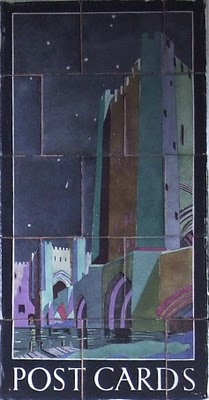

On the other side of the shop front. the bridge, gatehouse, and castle keep that advertise ‘Post cards’ are rendered in an extraordinary palette of purples, browns, and blues. The great tower seems hugely out of scale and oddly positioned in relation to the bridge. But who cares? This expressionist architecture lit by the stars (and the moon, which is presumably somewhere over the artist’s right shoulder) is simply stunning.

If the geography is uncertain, there’s no secret about the emotional terrain traversed by the car in the first panel. This image is all about getting away from it all, about surrendering to the romance of the open road. It’s a similar mood to the one conjured up by countless 1930s paintings of speeding automobiles and the artwork used on map covers. It’s about the freedom to explore, the seemingly limitless possibilities opened up by a good map and a set of four wheels.

The ‘Post cards’ panel is about what it might be like when you get there, and it’s a place that feels familiar, but has an odd unreality about it because of the peculiar proportions. The effect is reminiscent of the fantasy townscapes that F L Griggs (a great topographical illustrator in his day job) liked to draw when working for his own pleasure. Except that whereas Griggs mostly drew in monochrome, these tiles have had unreal colour poured in, for good measure.

How fortunate that these two images have survived, while the rest of the frontage has been adapted and painted over. Their light is from another age, but still it shines.

Apparently WH Smith’s business is more and more concerned with providing items for travellers at stations and airports. It would be nice to see them commissioning some new versions of these images to help reinforce this aspect of the brand. Though we probably shouldn’t hold our breath.

The local WH Smiths now contains the local post office, within the same building, the recreation of Calcutta’s black hole the inevitable result. Interesting subject tiles, became naff in the sixties and rapidly disappeared, except those Delft jobbies, even pre Antiques Road Show their value was recognized. The Fired Earth inspired revival, complete with ouch prices, seems to have fizzled out.

The surviving examples are wondrous indeed, the Bigg Markets Crown Posada and the aptly named Tiles pub in Edinburgh’s George Square being two fine examples, both pubs atmosphere greatly enhanced by sitting sipping in Victoriana / Edwardiana settings.

Lovely piece.

What a civilised lot Great Malvernians are; in some of the towns around here those glorious tiled panels would have been smashed to bits on hitting the side of the rubbish skip.

Earlier today, I read Nige’s review of Michael Holroyd’s A Book of Secrets, and was so taken by it I was on the verge of ordering from Amazon, then I read Philip’s post and thought: I’ll nip down to Great Malvern and buy it from W H Smith, and have a good look at those panels, but concluded that 90 miles was pushing it a bit.

The Shakespeare quote is wonderful. I must remember to use it when I’m next asked if I’ve got a copy of ‘The Fire Resistant Redhead – The Use of Retardants in the Newspaper Industry’

The panels are lovely, but I’ve never been able to look at WH Smith’s with much warmth since reading this obituary of Tom Hodges from The Times:

“Tom Hodges was accurately described in The Bookseller, 15 years after his retirement from WH Smith, as “a legend as a book buyer of uncommon shrewdness”. On an uncommon scale, too, for in his final years as book department manager he bought about £20 million worth of books, a prodigious sum in the early 1970s and then representing about 25 per cent of all British book publishers’ domestic sales, excluding text and technical books.

Thomas William Hodges was born in Bermondsey, South London, where his father had a fish stall — and was, Hodges always insisted, a brilliant fish buyer. He may, therefore, have enjoyed an innate buying gift, but this was about the sum of his inheritance, for he was the eldest of ten children and money was always short. However, he got a scholarship from his council school to Addery and Stanhope Grammar School. He matriculated at 16, a considerable achievement since he had daily, between school and homework, to put in two or three hours on the family fish stall.

He sought a job — it was 1929 — and was glad to take a clerkship in the London headquarters of WH Smith. The work was in reality a warehouseman’s under a system seemingly designed to achieve the maximum of lifting and handling. Called up in 1940, Hodges became a warehouseman in the RAF. He rose to sergeant, was mentioned in dispatches and always maintained that Smith’s, for all that they maximised manhandling and stored books by sizes rather than by publishers, was markedly less inefficient in the stores area than the RAF.

WH Smith was for many decades controlled by three powerful families, the Smiths, the Hornbys and the Aclands. Shrewd and long-headed, they were, their stationery department manager declared in the 1930s, “by reason of birth, education and social background incapable of appreciating the psychology of the lower and lower-middle classes who made up the vast bulk of their customers and staff”.

If the partners (after 1949, directors) were remote, the four managers were autocratic towards their large staff. (There were 350 people in the book department in 1947.) Hodges was determined somehow to make an individual mark, and on returning to his old job took, in his own time, a three-year Booksellers Association diploma course. He passed with honours and in 1950 was awarded the Bertha Barber Memorial Prize. (Princess Marina presented it to him.) Thus armed, he went to his manager saying that it was now 20 years since he had joined the firm and some promotion was surely due.

After three prolonged interviews (at which he was never invited to sit down) he gave notice — and was then given the newly created post of sales promotion manager for books. The title had a ring to it, but what he actually got was a shared table in a cubbyhole without his own desk or telephone.

Nevertheless, he managed to produce a stencil-copied weekly sheet, Books to Note, sent to bookshop managers advising them of the content and selling potential of about a dozen new titles. It was unique in Smith’s history and it came to the attention of the chairman, the Hon David Smith.

Hodges was made. When the book buyer — the number two in the books department — retired four years later, Hodges got his chance. A year or two later he was in some trepidation when he got a new boss, but the incoming manager, Reggie Last, knew an unusually able and willing workhorse when he saw one. He became Last’s assistant and then his deputy, and they worked together in remarkable harmony until 1965 when Last retired and Hodges was appointed merchandise manager and book buyer. He held this post until his retirement in 1974.

He continued to take a close interest in the buying side of the department’s work and for nearly 20 years he was essentially responsible for all Smith’s main book purchasing. In his early days he dealt with this almost single handed. As time passed and the annual value of his buying increased fivefold, to almost £20 million, he took on a few assistants — while 20 years after his retirement about 20 people were engaged on this task.

He was a courageous buyer, particularly in the light of the very different costs and values of the time. When he became book department manager, Smith’s turnover from all its widespread operations was about £100 million: 25 years later it was about £2 billion. The turnover of a useful small publisher could be less than £500,000. Hardback novels cost about £1.50; paperbacks about 35p. Among his biggest hardback orders were 150,000 Guinness Book of Records, 80,000 New English Bibles, 50,000 of volume three of Churchill’s war memoirs.

His opening orders for successive novels by Daphne du Maurier, Nevil Shute and Ian Fleming were for nearly 20,000 a time. He had, of course, a few failures — he thought the biography of Kathleen Ferrier was his biggest blip — but his nose for a successful book was generally acute. And his buying, on a scale never before envisaged by Smith, was not only significant to large publishers but even critical to the fortunes of smaller houses.

Hodges was certainly not an academic, nor even particularly well-read — though he claimed to read, scan or look at about 15,000 books a year. This was, perhaps, his real strength, for he had an instinct, natural, unsophisticated and shrewd, for the book an ordinary reader would wish to open. He was practical, too, demanding good (but not exorbitant) terms from publishers, never placing an order until he had seen a finished copy of the book.

Hodges, a cheerful, sociable, pragmatic man, had clear likes and dislikes. But no matter how expensively he was lunched and dined, how rich the hampers from grateful or hopeful publishers piled up in his home at Christmas, he never knowingly gave a fat order for a bad book.

He was for many years actively concerned with the Booksellers Association: as its president, 1972-74, he brought an unusual breadth of view and weight of authority to that office.After retirement he was for several years an active consultant to WHS Distributors, another Smith operation which (headed by a youthful Tim Waterstone) then began to turn in useful profits. He continued for many years as a director of the Book Trade Benevolent Society.

He married, in 1938, Minnie Ball. She died in 1996. They had one daughter.

Tom Hodges, book buyer, was born on July 8, 1912. He died on September 29, 2007, aged 95

The section that particularly sickened me was this one:

‘After three prolonged interviews (at which he was never invited to sit down)’

Gaw: Yes. The trouble is, retailers have makeovers every other year these days, replacing one dull plastic sign with another, so enduring materials like tiles are not favoured.

Malty: There are some grad tiled pubs in Edinburgh and elswhere: excellent settings for sipping.

John: Still chuckling over your last para.

Malvern is worth it if you’re in the area. There’s a terrific Victorian railway station, 19th-century villas shrouded in laurels, and the Elgar-echoing hills.

Philip, I’ve been to Malvern a couple of times and loved it. On each occasion, I recalled that unforgettable segment from Ken Russell’s BBC Monitor film of Elgar traversing the hills on bike, accompanied by his Introduction and Allegro for Strings. It was that film that encouraged me to go to Malvern. Wonderful…

I think these tiles are beautiful, not just because of the art (which is lovely), but because of that 1920’s optimism about the glamour of travel, later expounded so in the wonderful Shell Guides. As Gaw says, don’t think we could see similar nowadays, and what a shame that we so rapidly killed off the thrill of travelling