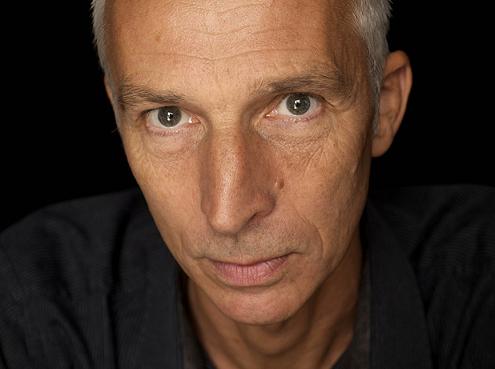

Author Rupert Thomson, whose memoir This Party’s Got to Stop was our most recent Book Club choice, provides an exclusive Q&A for The Dabbler…

Was This Party’s Got to Stop a book that you had to write, for reasons of catharsis perhaps? How long had you been ‘writing it’ in your head?

‘This Party’ is a book I always knew I would write – if I could find a way of writing it without upsetting those involved. Was it cathartic? Not really. I hoped the book might help me to find my way back to the mother I could not remember, to unlock my memories of her. Somehow I hoped I might be able to write her back into existence. It didn’t happen. The closest I got was in a car-park in Eastbourne in 2007, when I knelt down in the place where she had died – when I seemed, just for a moment, to feel her beneath my hand. As Wendell Kees says, though, in his wonderful poem ‘Girl at Midnight’: “What we have had we will not have again”.

Was it easier or more difficult to write than pure fiction? Were you able to retain the writer’s ‘chip of ice’?

I found the memoir much more difficult than fiction (not that fiction isn’t difficult!). In James Salter’s memoir ‘Burning The Days’, he talks about being ‘wearied by self-revelation’, and how he was unable to write for months at a time. That was what the first eighteen months of writing felt like to me – just plain wearying. I longed to escape into fiction. But the memoir was difficult in another way as well. I couldn’t work out how to use my imagination. I felt completely straitjacketed – crippled, really – because all I had to work with was what had actually happened. It was only in the second year of writing, when I suddenly realised that the book needed to become a kind of jigsaw or mosaic, that the book began to come alive for me. The qualities in the 1984 narrative that had seemed like weaknesses – the feckless behaviour, the loose ends – suddenly became strengths because they had something to play off.

How worried were you about how your family (and ex-girlfriends!) would take it, especially Ralph? How has he taken it, in fact?

After writing the first draft, I got cold feet – I was suddenly afraid I would be investing two or three years of my life in a book I might not be able to publish – so I began to write a novel instead. I spent two months writing the first draft of the novel. Then, against all the odds, I decided to go back to the memoir. There was a now-or-never feeling about it. After all, twenty-five years had gone by. I had enough distance on the material, but if I left it any longer I might start to forget. It was still a huge gamble, though – for legal reasons. As a result of living together in 1984, I had fallen out with Ralph and his wife, and I felt that to write an account of that time would be provocative at the very least, if not actually dangerous. Throughout the eighties and nineties I had often thought I would write the memoir secretly. It would be a clandestine book, written alongside the novels, but not published until after I was dead. A romantic idea, the secret book, but I never wrote a word. You can imagine my trepidation when the time came to send the finished manuscript to Robin and Ralph. Luckily, they both loved it.

One of the Dabblers described it as ‘absorbing and moving but not upsetting’, which he attributed to it being true and universal but not manipulative. Were you aiming to say something universal using your life, or did you just want to write about your life and see what came of it?

Even at the time I felt that what we went through in 1984 – what we had decided to go through – was pretty unusual. Most people are in their forties when they lose their last parent. They have a structure of their own – a partner, a job, children etc. They don’t have a spare seven months to go and live in their dead parents’ house. We were in our twenties, though, and we had all the time in the world. On the one hand it was like living in an anarchic commune – hints of Bruce Robinson’s ‘Withnail and I’ – but at the same time the set-up had something almost mythical about it: three brothers return to the house where they grew up…So this was death and grief and loss, but with a difference. I felt I had been gifted a unique angle on a subject that was universal.

At the outset I imagined the book would be a simple recreation of one crazy summer. That summer is there in the finished book, of course, but the book is many other things besides; a meditation on grief and loss, a portrait of a family, a healing journey – and most surprising of all, perhaps, a kind of love-letter to a long-lost brother. It’s a good example of how something you imagine you’re in control of can twist into a new shape beneath your hands. There is always this extraordinary, exciting tension between the writer and what is being written.

It’s a funny book, but you also have this ability to create a sense of unease and foreboding. Is that deliberate or just how it comes out because the people and behaviour you’re describing are so weird?

My books are often shot through with a sense of unease or foreboding. I once said, only half-jokingly, that paranoia comes naturally to me. When it came to the memoir, though, I was very careful to underplay the strange behaviour. So-called strange behaviour can actually be quite dull if you present it unselectively. What I tried to do was to choose the events or moments that illustrated what living in my family was like.

Do you think that your family is particularly odd or is it just that everyone, in their own way, is a bit mad?

There’s no such thing as a normal family, not if you look closely enough.

You drop in all sorts of shocks and oddities in the most deadpan, matter-of-fact way. The mention of the gay relationship at school; the violent eruption in the nightclub… it’s very effective – is it a deliberate dramatic device?

Not deliberate, no. I tried to render the events and conversations exactly as I experienced them at the time. I tried to get as close as I could to the life that I was living. That’s why I chose to tell the 1984 story in the present tense (the rest of the book is told in the past tense, since it is intended as a commentary or a gloss on the original narrative). It was a way of anchoring myself in that version of myself. Also – and more importantly, perhaps – understatement is always stronger than overemphasis.

One of the Dabblers was reminded of JG Ballard, specifically The Kindness of Women and Miracles of Life. Is Ballard an influence? If not, who is?

I’ve read Crash, which was unforgettable, and Cocaine Nights, which I found a bit anodyne, but although I have been compared to Ballard before, I don’t really count him as an influence. So who is? It’s a long list. Flannery O’Connor, Heinrich Boll, James Salter, Toni Morrison, Mikhail Bulgakov, Patrick Modiano. Jean Rhys, TS Eliot, Angela Carter, William Faulkner, JM Coetzee, Mervyn Peake, Gunter Grass…

What was the last Bowie album you bought on the day it came out?

Scary Monsters.

One passage that gave me a particular jolt comes in the final chapter, when you are reunited with Ralph after so many years and have a meal together, and you describe ‘something hallucinogenic’ happening, so that when you look away from his face you’re unable to retain the image of what he now looks like and instead see him as his nine-year old self. That struck me as brilliantly observed. Is there any particular chapter that you’re most proud of?

Impossible question. ‘Beautiful Day’, perhaps, because it seems so inconsequential, and yet it says so much. Or ‘Gravity Will Do The Rest’, because it acts as a kind of memorial or homage to my father-in-law. Or ‘Moonlight Reflects My Heart’ because it came as such a surprise to me. I’m proud of all the chapter titles, actually – I worked very hard on them – and I’m proud of certain sentences, which manage to be both simple and deep, ‘Some loose ends just get looser’ and ‘Having a family is like asking for it’ being two examples.

Is that it for memoirs now – will you be sticking to fiction or is there a sequel/prequel in the offing?

As a result of working on non-fiction for almost three years, I now have half a dozen ideas for novels. In 2006, when I briefly abandoned the memoir, I wrote the first draft of a novel about a nineteen year-old girl. It’s now in my filing-cabinet – as are the first drafts of three Barcelona-based novellas, which I wrote in the summer of 2009. I think all four will probably stay where they are – at least for the time being. The novel I’m hoping to deliver next year is set in Florence in the seventeenth century, and is based on a true story. I do have an idea for a non-fiction book about my half-brother, Hal. It’s not a prequel or a sequel, more like a sideways jump.

On a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 means that you’re fully addicted to social media and 1 means that you still write with that typewriter, how much do computers rule your life?

About 6. I write on a MacBook. I use the internet for research. I e-mail every day. I’m on Facebook, but only sporadically. No twittering.

On The Dabbler we have a feature called ‘The 1p Book Review’ in which we recommend out-of-print or unfairly neglected books that can now be bought second-hand from Amazon for a penny (there are millions). Any overlooked classics you’d like to recommend?

Can I mention some of my favourite obscure authors? Friedrich Durrenmatt. Alexander Trocchi. Denton Welch. Alfred Kubin. Weldon Kees.

A very interesting interview, the ability to swim through the bowl of spaghetti called family and stand on the far side with eyes focused and reasonably emotionally stable, no mean achievement, an aspect of life where spotting wood from trees is never easy.

Remembering people close to us as they were then and are now is often like putting together two and two and the answer being five.

Nice seeing Günter Grass get a mention, much underrated, the only mention of him in the recent German press was when the collection of his originals was lost when the Köln archive collapsed during excavations for the new U-Bahn.

I really enjoyed reading this interview, great questions and illuminating answers. I shall definately have to get my hands on a copy of the book

I once read a Trocchi book that I thought to be absolutely dreadful, it involved a woman wandering around the place having nonsensical ‘erotic encounters’, although I hear Young Adam is supposed to be good, as with Burroughs I guess a heavy heroin addiction makes the quality of ones output rather erratic