In a special guest post, author Sam Llewellyn explains why people misunderstand the purpose of maritime fiction, and why he founded the Marine Quarterly magazine…

Brrring, went the telephone. Hello, said a woman’s voice, I am a researcher for Woman’s Hour on BBC Radio 4 and we are doing a programme on the Sea in British Fiction, and we wondered if you would like to join in?

It was the sort of voice that emanates from a greenish room with no windows. Yup, I told it. Always delighted to talk about sea literature. Conrad, of course. Arthur Ransome, read little else between the ages of six and eight. C.S. Forester, read Hornblower by torchlight under the bedclothes. And of course Patrick O’Brian. Not only an exquisite grasp of Nelsonian seafaring in all its branches, but a roman fleuve infinitely preferable to Proust –

Never heard of any of them, said the BBC.

Naturally I ignored her.

Relationships are the stuff of fiction, and the sea is a great concentrator of relationships, I said. Only those who have spent weeks enclosed in a small hull with other people will have experienced this level of personal… well…

Intimacy? said the BBC, and I sensed a quickening of interest.

Certainly not, I said. The main thing about sea relationships is that they are conducted in a trance state induced by never getting more than four hours of the dreamless at one go.

The BBC at this point said something about To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf.

Ah, yes, I heard myself saying. I have never personally read this because I have always found V Woolf to be somewhere between precious and halfwitted. I believe To The Lighthouse is about a walk along some cliffs, or perhaps not. I further understand that like much British sea writing of the past 150 years it was perpetrated by someone sitting on the land looking at the sea. Some use this vantage point to good effect; Matthew Arnold, for instance, in his mighty Dover Beach. Most do not. Many current British writers, indeed, seem to think that the sea is a grey surface beyond the beach that looks like the car park behind the beach but is not as good because if you try to park a car on it the car sinks. So they sit and watch the waves break on the shingle, and each wave reminds them of a very sad yet heartfelt relationship because the wave has travelled mile upon mile, in motion yet static as to its constituent particles, and in the end collapses with a small roar. Then they write this bilge down, and people on Women’s Hour say advanced, forthright, significant, but I say the reverse.

Squawk, said the BBC. But I had entered the unstoppable phase.

‘As recent Icelandic eruptions have demonstrated,’ I said, bursting into inverted commas,‘we are the proud inhabitants of an island, and our very natures are defined by the ebb and flow of the tides round the ramparts of our home. So when I see self-regarding twerps making the element a metaphor for their own squalid preoccupations, I am repelled. They are too solipsistic to see the sea in terms of anything but health and safety legislation and their own tendency to nausea. God blast you for a bat-eared lily-livered herring-gutted bilge rat, madam, do you feel no heart-tug for the seagates? No sense of the perspective supplied by the sight of the Lizard coming and going over a long blue swell? This is an island nation, not a bathing machine for the bourgeoisie. Madam, I have smelt the land from the sea, and it is a warm smell of honey and spices and motherhood. But five miles downwind of wherever you are sitting it smells of fabric conditioner. When’s the programme?’

Beeeeeeee, said the dialling tone.

Once the blood had ceased to boil, a thoughtful mood kicked in. There are plenty of excellent sailing magazines, and magazines about shipping and fisheries and trade and marine conservation, all lavishly illustrated with splendid photographs. But there did not seem to be anything to read that held between one set of covers the reasons we go to sea, without resorting to metaphor.

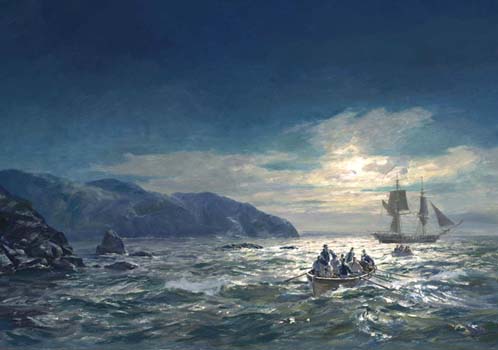

This may be because these reasons are very diverse. Some people go to sea because they are paid to do it. Others go because they are passionately interested in their boats. Others travel the seas looking about them at birds and beasts, catching the odd fish, speculating on the destinations of bulk carriers, the health of fisheries, the administration of navigation marks, and the voyages of hardy predecessors like Erik the Red and Harold Tilman. Occasionally they will find themselves racing. What they have in common is that they see the sea not across a beach, but from the sea. And when they have contact with the land, they will see that from the sea as well. This is the viewpoint of the Marine Quarterly, the journal I have founded and have the happy task of editing. Thank you, Woman’s Hour.

What a splendid sounding publication, I am sorely tempted to subscribe, especially as I live about as far from the sea as it’s possible to be on this island!

I’d like to read an article about the origins of the pink chino short in sailing club uniform. What did people wear prior to the advent of the pink short?

I can help you there, Worm. They wore galligaskins.

Invigorating stuff, Sam. Makes me want to get up at 5am, head down to the seafront and… sit in the car reading a book.

Fans of nautical fiction may be interested to read The Dabbler’s 1p Review of Patrick O’Brian’s The Golden Ocean.

Best etymological guess to date: R. Nares Glossary (1822) from ‘gallo-gascoins, being a kind of trowsers first warn by the Gallic Gascons, i.e. the inhabitants of Gascony’

Superb. Encore. Author! Author! I rolled in the gunwales. Or possibly the scuppers.

The BBC – at least in the persons of those who make such calls – is pitiable. I used to get requests to ‘defend swearing’. (Some idiot politician or self-promoting artist had said ‘Fuck’ in public). ‘But you mustn’t,’ titter, titter, giggle, giggle (and no, this is not aimed at women alone) actually say the words.’ ‘Why not? Don’t you consider this as condescending to your audience? Would you wish to be treated like an infant?’ Collapse of lissom party. Collapse, I am pleased to say, of further such communications.

and all very pertinent, what with the current hoo-haa generated about this very topic last week…

Excellent, this should have the BBC standing by their bilges, on the good ship cloud cuckoo land.

Hey!!!! in my absence the Dabbler has acquired a test run, or preview as they call it, fewer clangers I would suggest.