Jonathon Green continues his occasional ‘Heroes of Slang’ series by looking at American author George Ade…

He was a mid-Westerner (Indiana and thus a ‘Hoosier’ maybe from the rustic’s faltering ‘Who’s here?’) and admirably prolific (93 titles in the Library of Congress). He had been a columnist on the Chicago Morning News and began with stories of the city’s life before moving on to books and in time plays. He was something of a one-trick pony but the trick was certainly good at the beginning when the first funny books began appearing in the 1890s, and it kept coming and selling through to the 1920s, even if in the end it was more self-parody than originality.

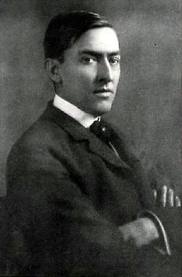

He was a huge hit, whose credo was ‘Give the People what they Think they want’ and whose first best-seller, Fables in Slang, sold 69,000 in its launch year of 1899. There were nine further collections plus Broadway hits, novels, essays and the rest. For the twenty years of his peak success every week brought him $1000 from newspaper syndication and $5000 more from stage royalties. The masses loved him; so too did the contemporary critics. William D. Howells saw him as that ever-awaited messiah, the great American novelist, Mark Twain, no mean exploiter of slang, added his tenpennorth of adulation, HL Mencken feted a genuinely original literary craftsman. And so it went. A town in Indiana, a football stadium (at Purdue University) and a World War II Liberty ship were all named for him. He had a 400-acre estate where he gave dinners for hundreds and parties for thousands. President-to-be Taft launched his campaign at one of them. And then he was gone. George Ade (1866-1944). Gone and pretty much forgotten too.

He was not alone in his era. Late 19th—early 20th century America offered a number of writers who depended on slang for effect. The journalist Helen Green (completely vanished from biographical record), who wrote of a Broadway theatrical hotel (The Maison de Shine) and the con-men, morphine addicts and vaudeville acts who frequented it. George Vere Hobart who published 23 books as ‘Hugh McHugh’, celebrating his character ‘John Henry’ and mocking his critics in prefaces that paraded his latest phenomenal sales figures. There was the cartoonist TA Dorgan, known as TAD, and CL Cullen, who wrote two volumes of Tales of the Ex-Tanks (ex-alcoholics, that is: what larks).

But Ade was the superstar. Perhaps it was his universality: fables have no geography, only a moral, which in Ade’s case was invariably laced with irony. Or his mid-Western background that comforted those who believed – then as now – that New York was Satan’s city. For many this made him even more important; an echt-American: as one critic noted, the mud of Indiana had stuck to him long enough to charm him against foreign influences. Some titles are in the British Library but he was too much the homeboy for mass consumption elsewhere.

He is quite sui generis, even if America had known other, earlier mid-Western humourists such as ‘Q. Philander Doesticks’ and ‘Artemus Ward’. But they tended to the folksy, and while Ade too dealt with folk, often his own mid-westerners, his treatment lacked their indulgence. And if in ‘John Henry’ one can see the glimmerings of Wodehouse’s Bingo Little (a young Wodehouse was in New York at the time, would he have read McHugh?) or a sniff of Runyon’s Broadway in Helen Green’s, Ade was a one-off.

It is not so much whether the wit stands up. For me it still works, at least the early Fables do, with their plethora of Germanic capitalisation and their insinuating titles: The Fable of the Good Fairy with the Lorgnette, and why She Got It Good; The Fable of the New York Person Who Gave the Stage Fright to Fostoria, Ohio, or The Fable of the Brash Drummer and the Peach Who Learned that There Were Others. Or equally early titles such as Artie (an office boy) or Pink Marsh (a black shoe-shine). But for the lexicographer, caring less for the text than for the words that make it up, the wit is irrelevant. What matters are the near 1,600 slang terms that Ade incorporates in his works.

Aside from the many examples of words that were already in use, the list of those first recorded by Ade is impressive. Just to look at some As, Bs and Cs, such first uses include abaft the wheel-house (crazy), stand ace or ace-high with (held in high esteem), aces and eights (excellent), acorn (the head), actorine, agony box (a piano), give or get the (fresh) air (to reject or be rejected), alfalfa (a bed), also-ran, angora (a fool, i.e. a ‘goat’), any old (anything, whatever, a general term of vagueness), hot baby (one who excels, gender irrelevant), baby-doll, to the bad (at a disadvantage), balled-up (confused), bamboo (Chinese), banjo-eyes (large, wide-open eyes), banzai (a spree), battle-axe (a formidable old woman), beanery (a boarding house), beef (a complaint) and beefer (a whinger), bellhop, below par (stupid), go big (to go well), black velvet (a mix of champagne and porter), blah (wrong, askew), on the blink (impoverished), blob (an insignificant individual), Catfish Row (the black area of town), chair-warmer (a supernumerary), chase (to pursue women), cheap (miserly), chickadee (a young woman), chilly (emotionless), clean house (to sort things out), clinch (to embrace sexually), coffee-grinder, (any form of rickety machine) and cough up (to confess). Not all have lasted, and some senses have changed, but the knowledge of his linguistic era is undeniable.

Nothing lasts. The star of the 10s and 20s became the invisible man of the 30s and 40s. He failed the new era’s tests: his work had never addressed issues and the Depression, the Spanish Civil War, the imminence of World War II all militated against him. He declined, as SJ Perelman would note, to a three-letter word clued as ‘Indiana humourist’ in easy crosswords. Yet nostalgia plays its role, and death too, and if Ade died in 1944 then his small literary revival also dates from that period. Whether anyone re-read the books is arguable but he graduated from humourist to social historian: his characters, their settings and their speech offering a special insight to the time and place in which he created them.

Ade died rich and more important happy. It had not been simply giving the people what they thought they wanted: they had wanted it for real and paid accordingly. He knew what he could do and had no wish to transcend it. Let us give him the last word: ‘It is proper to enjoy the Cheaper Grades of Art, but they should not be formally Indorsed.’

Very interesting stuff indeed Jonathon, I love reading about all these stories about people who were the very height of fame who are now almost completely unknown. Nige used to have a good line in unearthing some really obscure ones on his blog too. Where would we be today without the term ‘battle-axe’?

Yes you always wonder which current literary giants will be similarly forgotten a few decades hence. Most people seem to plump for Ian McEwan.

Black Velvet – now there’s a weird drink, eh? On the face of it, the last thing you want to do with a bottle of champagne is stick some Guiness in it; and the last thing you want to do with a nice pint of Guiness is put champagne in it..

I’m not a novelist but there was nothing more salutary when reading for the dictionary than visiting the stacks in the London Library and surveying the ranks of triple-decker Victorian novels – sometimes dozens from the same author – which had once been best-sellers but are now bowed so low beneath a century’s dust that the library keeps a special brush at the issue desk so as to clean them up before allowing them on a rare trip out.

As for black velvet: if you don’t want yours, Brit, pass it over here please.

I did say ‘on the face of it’…Like the British constitution but unlike, say, Marxism, Black Velvet works better in practice than in theory.

Thanks for yet another fascinating piece, Jonathon, and another name new to me. Having read your post, I went to Project Gutenburg and inserted the name George Ade in the search engine. It threw up seven books, and 384 downloads. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/search.html/?default_prefix=author_id&sort_order=downloads&query=3917

I decided to sample George’s work by downloading the least popular: ‘Knocking the Neighbors’, and wherever I dipped I found myself smiling or on the verge of a chuckle. I look forward to reading it from start to finish.

I was left wondering: how many of those 384 downloads were from after your post appeared this morning?

At least one anyway, John.

True, Brit.