Despite still being less than a year old, The Dabbler has already amassed a rich archive of wonderful content – and, since our readership has grown exponentially, most of you won’t have seen a lot of it. On Sundays, Bank Holidays and other occasions we will be digging out some articles which deserve another moment in the sun. Frankly it would be criminal not to.

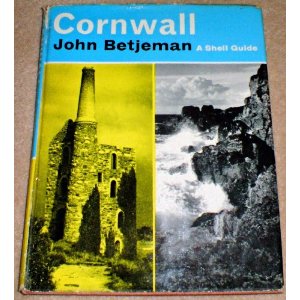

Our first ‘Worth Repeating’ is this article on Shell Guides, which first appeared in November 2010. Shortly afterwards its author, Alexandra Harris, found literary stardom and won the Guardian First Book Award for Romantic Moderns. Coincidence? We hardly think so…

Shell’s irrepressible advertising director, Jack Beddington, was keen on Betjeman’s idea that the company might sponsor a series of guidebooks to help the new motorists find their way around. Betjeman duly became the editor of Shell County Guides. The list of authors he managed to recruit for the pleasant but excessively time-consuming job of guide-writing indicates the topographical predilections of the period’s cultural personalities. By the mid-1930s it seemed that everyone was out gazeteering: Betjeman in Cornwall and Devon, Paul Nash in Dorset, John Nash in Buckinghamshire, John Piper in Oxfordshire, Robert Byron in Wiltshire (though the excellent Wiltshire gazetteer was provided by Edith Olivier and became a model for all the others).

Betjeman had grown up with Victorian guides of the ‘Highways and Byways’ variety which were intent on taking the reader on a quest for authentic England. Authentic, in this case, meant medieval and vernacular; anything later tended to be treated as a violation of the old country. These guides from a previous generation were now the subject of much fondness and much hilarity. After dinner at Fawley Bottom the Betjemans and Pipers sometimes played a game at their expense. Each player would produce guidebook entries in parody ‘Byways’ style and, predictably, England’s oldeness took on some fantastical proportions. Friends reported that Myfanwy Piper was especially good at inventing ethnographies and dark, terrifying customs for medieval villages.

The Shell guides had fun with mysticism (pixies, cuckoos and witches populate every mile of Betjeman’s Cornwall; Nash’s Dorset is stalked by dinosaurs) but they also tried to get away from fairyland. Piper’s Oxon is an essay in the pleasures of ordinariness. He was glad to find a sane, unselfconscious county where ‘the fields are flat and have the usual number of cows’. Turning his back on the venerable spires and deciding not to include Oxford city, he went off to find unsung outposts, the bits of countryside between places. Piper’s Oxfordshire is not a land of touristic sensation. Old England is allowed to be also a modern lived-in country. A photograph of clustered advertisements which would have troubled purist preservationists is fondly captioned ‘a tree of knowledge’, and an oval photograph with faded edges evokes nostalgia only to affront it with a big sign advertising a ‘super cinema’.

Betjeman gave his writers special instructions to look at places not previously thought worthy of mention, particularly ‘the fast disappearing Georgian landscape of England’. He wanted the Shell Guides to include ‘churches with box pews and West galleries; handsome provincial streets of the late Georgian era; impressive mills in industrial towns; horrifying villas in overrated resorts’. Seeing Britain with Shell meant looking beyond authentic windy villages to enjoy fakes and masquerades; it meant adopting a Georgian taste for classical architecture and antiquarian eccentricities.