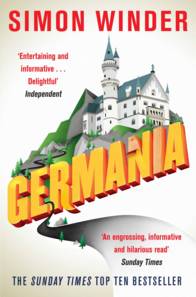

Simon Winder is the author of Germania, A Personal History of Germans Ancient and Modern. It was described by the Telegraph as ‘an unusual and very entertaining tour of the oddities of German history’. Simon is also the author of The Man Who Saved Britain, a personal take on the impact of James Bond, in Ian Fleming’s novels and films, on British identity, both at home and abroad. He is Publishing Director at Penguin Press.

This is a group of 20 books which I came to really like in one way or another while writing Germania. They are a disparate bunch but are all a pleasure to read and say curious things interestingly. There are two sad omissions, Heinrich Mann’s Man of Straw and Theodor Fontane’s Before the Storm, which are the most marvellous historical novels about Kaiser Wilhelm’s and Napoleonic (or anti-Napoleonic) Germany respectively, but they are both currently and very sadly out of print.

Three major works: Everything always has to kick off with Buddenbrooks. I spent ages trying to come up with some clever-clever alternative, even just from within Mann’s other work – but Buddenbrooks lays them all waste. One of the greatest of all family sagas, a homage to and a critique of the Hanseatic merchant tradition of northern Germany – beautifully written, endlessly thought-provoking: a rite of passage (and an enjoyable one too) for anybody even faintly interested in Germany.Johann Grimmelshausen was a young soldier in the Thirty Years War and late in his life he wrote Simplicissimus, one of the first German novels, a startlingly grim, brilliant and odd book filled with scenes of Bosch-like cruelty. Towards the end it loses focus rather badly with nonsense about magic mountain lakes, but the whole thing is so episodic that it doesn’t matter much that there is no real climax. This is a hugely influential book which through the sheer accident of its being written and then later rediscovered allows us a direct link to the people of one of the worst times in German history. Eduard Mörike’s Mozart’s Journey to Prague shows that something can be ‘major’ while also being tiny, indeed barely more than a long short story – but still perhaps the most convincing and believable portrait of a great artist going about his life, in this case travelling with his wife through the Bohemian woods on his way to conduct the first performance of Don Giovanni. This edition also includes a selection of Mörike’s poetry, which in all honesty can be a bit twee and clunky – but has a central place in the history of German culture because of its being set by Hugo Wolf into some of the most beautiful songs ever written.

Three fabulists: the tones of these three books are quite different from one another, but they remain related by the strange German ability to evoke place, character and atmosphere with bizarrely few words – indeed some of Hebel’s stories in The Treasure Chest are just a few lines long and yet his cast of larrikins, inn-keepers, drunken soldiers and crafty con-men are as fresh today as when they were first written down for the entertainment of Rhineland newspaper readers two centuries ago. The Brothers Grimm are of course the re-tellers of some of the most famous stories in western culture – this Selected Tales translated by Joyce Crick includes all kinds of less familiar goodies and there is something very convincing (and hair-raising) about Crick’s translation which makes the reader really care about the princesses, woodcutters and anxious old kings. It is certainly a welcome reminder that you should always be polite to odd looking little old men encountered in the forest. The Tales of Hoffmann have drifted around my head for as long as I can remember and possibly may be the deep background reason it felt sensible to write Germania in the first place – ‘The Mines of Falun’, ‘The Sandman’, ‘Madame de Scudéry’ – if you have not read these twisted, deeply unsettling masterpieces then you are extremely lucky as you should now do so without wasting further valuable time – and if you have, then you just know that you will somnambulistically be drawn back to read them again!

Three examples of Bildungsroman: the quintessential German form – a young man decides to walk down the road, leave his town and see a bit of the world and is changed by what he finds. Funnest of all is one of Germany’s best-loved books:Life of a Good-for-Nothing by Joseph von Eichendorff, a miniature cavalcade of absurd happenings as the passive but cheerful hero is flung across Europe, entangled with aristocratic beauties and Italian robbers in a way that seems to anticipate surrealism – indeed much of the book feels like a de Chirico painting, but an oddly jolly one. Adalbert Stifter is almost unknown in Britain and that is a shame as his greatest works have the flavour of a literary equivalent of some of Schumann’s piano music – a strange mixture of beauty and underlying anxiety. He was also a remarkable painter and spent much of his time in the mountains between Austria and Bohemia hiking, painting and writing. He wrote Rock Crystal, the definitive tots-in-peril-in-the-mountains novella – but also the marvellous The Bachelors, where in pursuit of an inheritance a young man walks through a dazzlingly described mountainscape to meet a mysterious old man living in almost total isolation in an abandoned monastery on an alpine lake. Each moment of the journey is so vivid that it feels like the lived experience of the reader and the old man’s house is one of the greatest fictional dwellings in all literature – perhaps only equalled by the rose-covered mansion in Stifter’s own later work Indian Summer. The grotesque final Bildungsroman is Ernst Jünger’s Storm of Steel where the journey from innocence to a cult of ferocious violence pretty much destroys the genre. One of the greatest books of the First World War Storm of Steel gives an unmatched picture of the attraction of fighting, of comradeship and of killing as a way of life. It was for many years viewed with distaste as a proto-Nazi text, but now it feels like a strange sort of privilege that through Jünger’s book we can see into a terrible glimpse into a world in which fighting might be desirable. A very eerie work by any standards (it sets out to be non-fiction, but it is better read as a novel), it is particularly gripping for British readers as it portrays the British troops in the opposing trenches as athletic, blood-hungry monsters.

A group of Austrians: Stefan Zweig and Joseph Roth were two great Jewish writers who memorialized both the last years of the Habsburg Empire and the strange, broken up, much reduced Central Europe after the First World War. Their work now has an added irony (although this seems too weak a term for this) in that the rueful world they lived in was also about to be swept away in the most horrible way. People tend to be fans of one or the other, but it seems futile to choose. Zweig’s Beware of Pity is a novel that cannot really be described without giving away key aspects of the story: the narrative is a series of shocks and reversals set in a garrison town before 1914 and is a classic variant on the story of the naïve and ordinary young soldier falling in love with posh people living in a castle, with irreversible and nail-biting results. Joseph Roth’s most famous book is The Radetzky March – an intimate epic of a family in the service of Austria-Hungary, suffused with a painful sense of loss and dislocation. Robert Musil’s The Man without Qualities is the monster of all monsters – a vast, unfinished work which (like that other great post-Habsburg novel The Good Soldier Svejk) gains hugely in stature because it is unfinished – no ending could be anything other than bathetic. I cannot imagine reading it twice, but first time round it is extremely entertaining, flattering to the reader and has at its heart a single marvellous invention: a ridiculous committee convened in anticipation of Franz Josef’s 70th year on the throne in 1918 to work out suitable patriotic displays and outpourings. Of course the reader knows that in 1918 Franz Josef will be dead and the Empire destroyed by War, but the novel endlessly (almost literally) defers the passing of time that would put the committee’s work in question. Thomas Bernhard’s Old Masters (1985) is a haggard, ferocious and very funny short novel pouring scorn on the entire course of Austrian culture with his two dyspeptic old anti-heroes sitting in a gallery deriding Gustav Mahler, cakes, toilets, Adolf Loos – the effect is just a great relief and its venom a tonic.

Two painful backward glances: Günter Grass’s Crabwalk is an almost documentary-like analysis of the catastrophic final period of the Second World War when Germans themselves had to live with the consequences of their acts and millions of Germans fled from the east, trying to outrun the Soviet army and losing their homes forever. Grass focuses on the single worst civilian shipping disaster (far worse than the Titanic): the sinking by a Soviet submarine of the Wilhelm Gustlof, a former cruise-ship crammed with refugees. It is as good a book as Grass’s far more famous The Tin Drum. W.G. Sebald lived much of his life in England but was always a major German writer who was inspired in part by the landscapes and people of England. The Emigrants may be his greatest work: a series of apparent interviews by Sebald of four individuals who had to, because of the events of the 20th century, leave Germany. It is never possible to tell what elements in the stories may be true and what false, but quite rapidly this becomes irrelevant as the reader is swept along by a series of painful and moving reflections on life lived in painful times.

And last off: three distinguished visitors. George Macdonald Fraser’s Royal Flash is offensive in all kinds of ways, but nonetheless a masterpiece of comic tone and prose and in its lovingly detailed (and completely ridiculous) picture of a fictional German duchy of an old-fashioned sort a special treat for anyone who has, like me, spent too long wandering around such places. Vladimir Nabokov’s Laughter in the Dark is a good representative of the books he wrote in his years in Berlin and as well as having an enjoyably dank plot preserves perfectly the headachy patch in Weimar Germany’s depressing chronology just before the Nazi seizure of power. Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow is here because although it is a work of pure imagination (and imagination of a mind-spinning kind), it was in my head throughout writing Germania. The Second World War as a landscape defined by the parabola imagined or actual of Nazi rockets is a once in a generation great idea that I’m not sure can ever be beaten. Pynchon’s vision of life inside the slave-labour V-2 rocket factories in tunnels built into the mountainsides of Thuringia led me to visit the real things. It was then that I decided to end my book in 1933, as my own jokiness could not start to encompass somewhere so completely terrible.

Thank you – I’ve been after an annotated list of this kind for ages, and this post is a great deal more, and a great deal more entertaining, than that. (Lifechanging trip to Berlin in 2008 etc etc).

There is something a little frightening about the news that Musil’s novel is unfinished..! It’s been glowering at me unread from the shelf since I came across it in Clive James’s ‘Cultural Amnesia’, in paperback the size of a stage amplifier. Is it better to start with ‘Journey to Prague’?

There is one thing, though – you describe “Royal Flash” as “offensive in all kinds of ways”, and as I can’t think of a single way myself, wonder if you’d be prepared to elaborate – perhaps something I read 25 years ago at school would read differently now?

Firstly Simon, Germania is in the prominent, always to hand section on the bookshelves of the following….Simone D, Silka L, Simon R, Klaus Dieter L Erich B, George S plus that evil looking broad, Rosa Kleb’s double, who has the apartment below juniors in Schillingstraße, you are obviously well read among the Krauts. The downside may be that at least one of the above has a well thumbed copy of the allegedly illegal Mein Kampf sitting out front.

Grass and Roth I read and like, prefer Mörike’s words set to Wolf’s music and sung by Fassbinder or the Lancashire lass, hoping the Dabblers will allow me a slot about him sometime.

Did you know that sadly the entire Grass collection of originals was lost in the recent collapse of the Köln Stadtarchiv, falling into a hole excavated beneath, extending the U-Bahn, the ramifications of which are still twanging around the city’s lawyers.

Tut tut, where’s The sturmy and drangy Sorrows of Young Werther?

Wow so much good stuff! I’ve got a fair few of these books already, and co-incidentally I picked up Storm of Steel in an oxfam on sunday, now just purchased Tales of Hoffman on your recommendation!

Another good german book is The Reader by Bernhard Schlink

And lets not forget The Golden Bomb an excellent anthology of German expressionist stories which I’m pleased to see is still in print from the indispensible Atlas Press. And it appears the last few copies are up for 6 quid! Get ’em while you can I say

http://www.atlaspress.co.uk/index.cgi?action=view_backlist&number=17