Jonathon Green – visit his website here – is the English language’s leading lexicographer of slang. His Green’s Dictionary of Slang is quite simply the most comprehensive and authorative work on slang ever published. Today Jonathon continues his epic survey of the Seven Deadly Sins of Slang with Greed…

‘This, sir,’ replied Silas, adjusting his spectacles, and referring to the title-page, ‘is Merryweather’s Lives and Anecdotes of Misers. … I should say they must be pretty well all here, sir; here’s a large assortment, sir; my eye catches John Overs, sir, John Little, sir, Dick Jarrel, John Elwes, the Reverend Mr Jones of Blewbury, Vulture Hopkins, Daniel Dancer–‘ ‘Give us Dancer, Wegg,’ said Mr Boffin.

Dickens Our Mutual Friend (1865)

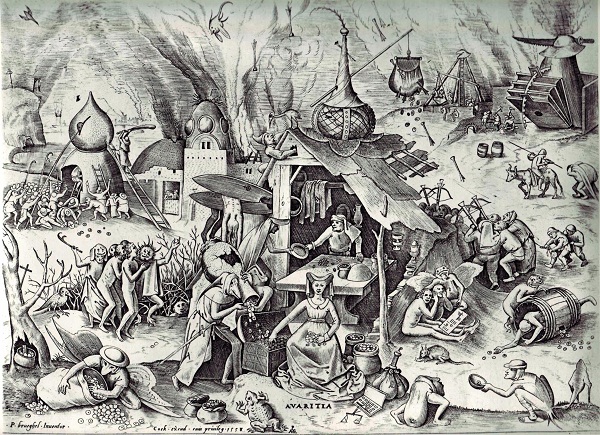

Despite undeniable resemblance and natural synonymy, in the taxonomy of sin greed stands apart from gluttony. Gluttony is limited to food, greed deals with everything else, all those uncovetables as listed in Exodus 20:17: thy neighbour’s house, wife, servants, domestic animals nor indeed ‘any thing that is thy neighbour’s.’ Money, the rationale of Noddy Boffin’s cast of misers, is not mentioned: it had yet to exist. The word is relatively ‘new’, a 17th century back-formation of greedy, which goes back to a Sanskrit root grdh and is first recorded in 971. One senses the baring of teeth. The waters are muddy: greedy means desirous (which almost brings in lust) but its earliest sense refers to hunger ravening after food and the avaricious groping for material things comes a few decades later. Those who catalogue the dancing of angels upon pinheads might find a syllogism here. I shall pass to what I know.

Despite undeniable resemblance and natural synonymy, in the taxonomy of sin greed stands apart from gluttony. Gluttony is limited to food, greed deals with everything else, all those uncovetables as listed in Exodus 20:17: thy neighbour’s house, wife, servants, domestic animals nor indeed ‘any thing that is thy neighbour’s.’ Money, the rationale of Noddy Boffin’s cast of misers, is not mentioned: it had yet to exist. The word is relatively ‘new’, a 17th century back-formation of greedy, which goes back to a Sanskrit root grdh and is first recorded in 971. One senses the baring of teeth. The waters are muddy: greedy means desirous (which almost brings in lust) but its earliest sense refers to hunger ravening after food and the avaricious groping for material things comes a few decades later. Those who catalogue the dancing of angels upon pinheads might find a syllogism here. I shall pass to what I know.

Uncharacteristically muted as regards envy, slang seems more comfortable with what Old English called yissing (Old English gítsian, covetousness) and winninghead (the earliest sense of winning was financial, not sporting gain). There’s the Caribbean cubbitch, from covet and trimble, which suggests one who ‘trembles’ with desire, and South African snoep, which simply borrows from the Afrikaans. There’s the self-explanatory concept of gimme, which gives the material gimme girl, and the emotional gimmies, which one may ‘have a case’. In America there’s the gimme cap, which refers to logo-blazoned baseball caps which are distributed free in order to spread the brand name. The original gimme wasn’t a cap, it was a pack of cigarette papers, but the promotional headgear lasted longer in every sense. A look back to gluttony will shows that some of those terms can be used outside the food context, and the same works in reverse. Piggish and hoggish straddle every variety of greed. Sharking, however, resists food, and the harbour shark prefers maerial to meat. Spoony, utensil imagery notwithstanding, derives from spoon, initially a fool, and thence an infatuated lover; and defined as that which is ‘open’ and ‘shallow’. In this case it is presumably scooping up cash.

It is, however, those that are tight and whose pockets are deep, that sees slang at its most expansive. The miser. Mr Boffin’s volte-face always rings a little false, but Dickens needed his happy ending. Slang goes the other way. As ever it revels in the downside, and its litany of the ingordigious lets misers grasp without shame.

The man with no hands or the one-way kid (money comes in, it never leaves) has one-way pockets and is maybe a vip (for viper: he ‘bites’ his victims) and even a vinegar pisser (the miser is invariably ‘sour’; after all, his roots lie in Latin miser, meaning wretched). He’s a scurf (as in the disease, and which also applied to an employer paying sub-standard wages, as well as the workers who were willing to take them). He can be a toadskin, a name based on the proverb ‘his purse is made of toadskin’, which signifies greed: the toadskin in a variation on the better-known frogskin, both mean a dollar and the image is of the ever-stuffed wallet. There are also chinch (from old French chiche, parsimonious), chuff, which in the dialect original means surly and ill-tempered, and New Zealand’s gorsepocket.

Above all it’s about grasping. Having and holding. The closed hand. The tight fist. Or for slang the tight arse or tight hand. The old flint and the skinflint whose greed might lead him to wield his flensing knife in search of profit from the impervious stone. Stone underpins moss-dog too: he hangs on to his wealth like moss on a rock. There are the grab-all and the grab, thus the Swell’s Night Guide of 1846, warning against a madame: ‘Mother Ruckers, is a rank screw, a dead grab and a stinging nark.’ A screw is a miser as well. The scrape-all ‘cleans up’ whatever he can secure. Gripulous, in standard English, he is a gripe (both a standard term for grasping and for a vulture), gripes, gripe-all, gripe-man, griper, gripper, gripe-fist, gripe-penny and gripe-well. In the UK a tizzy-snatcher (from tizzy, a sixpence), across the water he’s a nickel-grinder, a nickel squeezer and a nickel nurser, set down in the 1926 Wise-Crack Dictionary as one who ‘has a passion for seeing that his nickels don’t stray.’

Above all it’s about grasping. Having and holding. The closed hand. The tight fist. Or for slang the tight arse or tight hand. The old flint and the skinflint whose greed might lead him to wield his flensing knife in search of profit from the impervious stone. Stone underpins moss-dog too: he hangs on to his wealth like moss on a rock. There are the grab-all and the grab, thus the Swell’s Night Guide of 1846, warning against a madame: ‘Mother Ruckers, is a rank screw, a dead grab and a stinging nark.’ A screw is a miser as well. The scrape-all ‘cleans up’ whatever he can secure. Gripulous, in standard English, he is a gripe (both a standard term for grasping and for a vulture), gripes, gripe-all, gripe-man, griper, gripper, gripe-fist, gripe-penny and gripe-well. In the UK a tizzy-snatcher (from tizzy, a sixpence), across the water he’s a nickel-grinder, a nickel squeezer and a nickel nurser, set down in the 1926 Wise-Crack Dictionary as one who ‘has a passion for seeing that his nickels don’t stray.’

He pinches. The pinch-back and pinch belly refuse to hand over enough money for their victim to buy clothes or food; the pinch-commons grabs, metaphorically, all the provisions that are provided for group consumption; there is the pinch-fist and the pinch-fart. The pinch-gut tightens their own belt as well as that of others; the 17th century Navy provided pinch-gut money, explained as being ‘allow’d by the King to the Seamen, […] on Bord the Navy […], when their Provision falls Short.’ He can be a nipper and a sting-bum. Old huddle ‘huddles’ around his money; while old hunks or hunx defies explanation. Perhaps the image is of the celebrated ‘Harry Hunks’, a bear kept in 17th century London for baiting (there were others who earned names: ‘George Stone,’ ‘Ned Whiting,’ and the most famous, ‘Sackerson’ who is name-checked by Shakespeare): bearlike, the miser ‘hugs’ his money.

Finally, there is Yorkshire. Half my family arrived there from Mitteleuropa in 1920 (Doncaster? Don’t ask me) so I’m equivocal, but slang is less forgiving. No sylvan vet fantasies or cobbled streets. It’s all ‘Niver do owt fer nowt’ and Yorkshiremen are seen as mean. There’s the Yorkshire bite, over-reaching and greediness; the Yorkshire compliment, a gift that means nothing to the donor and is useless to the recipient, a Yorkshire estate, money that is in prospect but not yet handed over; a Yorkshire reckoning where every member of the company pays for themselves and come (the) Yorkshire over or put (the) Yorkshire on, to cheat. A Yorkshire cravat is a hangman’s noose. Tough, those Tykes.

Do you have a question for Mr Slang? Email it to editorial@thedabbler.co.uk and we’ll send it on to Jonathon.

Yorkshire compliment – a gift that means nothing to the donor and is useless to the recipient Now that one will come in very handy come Christmas time….

And “Mother Ruckers”? There’s a song about that.

I always use the phrase ‘tight git’ – where does the word ‘git’ come from as it’s usually used in a miserly context..?