The discussion sparked off by 1066 and All That reminded me of something I’d written on how one’s appreciation of history changes over the years – in particular, one’s attitude to its ‘knowability’. I’ve tried below to categorise my own attitudes over time. I would think that in our mostly post-ideological age it’s a fairly typical intellectual progression.

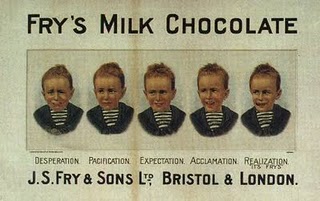

Each phase has its own particular character, rather like Fry’s Five Boys, as pictured on the chocolate bar of blessed memory (before my time, but I spent a while working in the old Fry’s factory near Bristol where this bit of confectionery history was unavoidable).

Curiosity

Naturally, when you start studying history at school you know very little – some basic stuff taught in early years and what you’ve gleaned from films, the odd book, and trying to keep up with conversations between your elders (Dad and Taid debating whether Monty was a good general or just a show-off, or whether Patton was right in wanting to head for Berlin – usually kicked off by a Christmas war film: The Battle of the Bulge, A Bridge Too Far, Patton). You look forward to learning more, it all seems so very intriguing and might make you a man-of-the-world. Frustratingly, you find there’s not a lot (if anything) about generalship, but more than you’d want about three-field crop rotation.

Certainty

You begin to learn proper history at what was ‘O’ and ‘A’ Level, and then at the more rarefied degree level, if you pursue it that far. Things at bottom seem to be quite clear and straightforward. You tend to be persuaded by grand narratives, or at least the one that appeals to your instinctive view of the world: Marxist, Whiggish, Darwinian – perhaps nowadays Environmentalist. You suspect you have access to some higher knowledge and wonder how a lot of your elders don’t know any better – it’s obvious what’s been going on, isn’t it? For me, it was some vaguely Marxist/progressive idea that progress was taken forward by revolution. For instance, Britain’s biggest problem was it hadn’t experienced a bourgeois revolution, unlike France, leaving it encrusted with outdated and irrelevant institutions, conventions and attitudes.

Doubt

You continue to read around and, more importantly, you live a bit too – getting a sense of what people are really like in the outside world. Things don’t fit together as neatly as you guessed. You experience foreign countries and cultures. Is the hyper-critical attitude to where you grew up justified? You begin to doubt if the truth really is out there. All these grand narratives turn out to be partial or inadequate explanations of the world. Things you thought irrelevant are meaningful. Meanings are layered, non-obvious, paradoxical. Ideas matter, people matter, interests matter, no-one is in control really and no-one ultimately knows what the hell is going on. This is troubling. And some seem to have already reached this conclusion. Is it all just one damned thing after another? Is it a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing?

Humility

However, you begin to accept contingency; it implies that life intrinsically contains an element of freedom. Instead of there being one big source of meaning, there are instead a succession of meaningful events. Establishing why they’re singularly meaningful is the fun of it. Tentatively you begin to appreciate history’s fundamental mystery; its subtlety, its profundity, its complexity. The satisfaction comes from struggling with this intractability. You may never come to the definitive truth about something, the chances are it may not exist. But to travel is better than to arrive. There probably is no Holy Grail. But there is a fantastic adventure to be had in trying to track it down, one which might teach you a great deal about the world. Galahad was a boring prig, it was Lancelot who experienced the exciting stuff.

Next?

As far as I know, the last phase is the end-point. But who knows? Perhaps I might end up an ideologue of some sorts, or perhaps a nihilist. Life, like history, can be full of surprises.

I suspect that 5-stage process also applies to politics and religion…

Curiosity: these days has to include “Horrible Histories.” Can’t underestimate the importance of those books (and the very funny TV programmes) to the young historian in this house, who now says that history is his favourite subject. Also, the time travels of Dr Who.

Doubt: think the late Prof Burke, my wonderful professor at Portland State, and a diplomatic historian, would have agreed with all that, particularly, “no-one is in control really and no-one ultimately knows what the hell is going on.” He used to say most students just don’t get that politicians were/are generally choosing to do the least worst thing from a series of dreadful choices. Of course, even in my wise old age, I choose to ignore his wise words and thus am not cutting the current Coalition any slack, but as it’s not history yet, I am deeming that to be a fine intellectual stand.

Your Prof Burke sounds sensibly Burkean, Anne.

History is unknowable because it is too complex, but that doesn’t make it any less worthwhile to study.

Prof Burke was especially interesting on the decision to drop the atomic bomb. On the one hand, he had all the reading and sources down pat. He was an old time, Boston born, Democrat, and would talk of the legacy of Regan and the first Bush through clenched teeth. On the other, he’d joined the US navy at 17, right at the start of World War II, and therefore had been on ship, heading towards Japan, knowing that if a land invasion was required, it would be unbelievably awful for him and his young colleagues. This always prompted great debates between him and young students, all overflowing with hindsight and wildly quoting Howard Zinn. (And I don’t think any of them had yet seen “Bridge on the River Kwai.”)

The question, I suppose is whether you can have history without some form of what psychologists call the ‘historical fallacy’ — that is, the almost universal tendency to look back on a sequence of events from the perspective of the outcome they have produced, and to impose a frame or narrative on the events in which the outcome is intrinsic to their meaning. It may be a fallacy, especially when outcomes are somehow smuggled back into the process as causes, but aren’t we all hardwired to do something of the sort (e.g. in interpreting our own lives)?

It’s like that very interesting post that nige made on his blog recently about the annoying way that tv producers fill up every period drama with period furniture, when the reality is that most people’s decoration is a random mélange of times and influences – much like the actual creation of historical events

“not a lot (if anything) about generalship, but more than you’d want about three-field crop rotation” 😉 I veer between thinking that people whould know everything about history and thinking that people should know nothing about it. Selective reading – or, even worse, partisan education – seems to have produced some pretty polarised communities over here.