Ian Vince writes the regular Strange Days column in The Daily Telegraph and is the author of the highly recommended new book The Lie of the Land. He is also the founder of the British Landscape Club.

It was a bright day in early winter, the sun was shining and a substantial fall of fresh snow lay pristine under an arching blue sky. I stepped off the train at Lairg, midway along the line to Wick in the far north of Scotland and wondered whether the postbus would be in the station car park or somewhere between there and Lochinver, lodged up to its headlights in snow.

So I counted myself lucky to be greeted by Donald and his postbus. The morning collection was, by his account, a little hairy but he got through in the end and by the early afternoon, with a slight thaw under way, we were soon heading off on the final forty miles of my journey to the top left hand corner of Scotland.

I was on a simple expedition, to find Britain’s oldest landscape, and I could not have picked a better day for it. Everything assumes a mantle of unfamiliarity in the snow and as a newcomer, with every twist and turn of the road already a new experience for me, the layer of snow added a sense of an approaching surprise, an imminent unveiling, never resolved in its entirety. It also made everything seem quiet, tucked up, quiescent and still; the absolute antithesis of its own creation – of all our creations – a brimstone-fuelled and -filled affair, a sulphurous, acrid hell or a million year monsoon, the various infernos and Biblical deluges that started the world.

Despite the thaw, as we made our way up Strath Oykel there was still plenty of snow around and that was good news for any expedition for which the operational parameters boil down to ‘look at the ground’ because in those circumstances, snow, as Donald observed, “reveals more than it conceals”.

He was right. The overall structure of things becomes more visible when detail is obscured; in such conditions, for example, the thin horizontal terraces – bedding planes – that girdle the mountains are picked out like the lines of ribbing on a gargantuan airship. Reduced to its essentials, snow-bound scenery is an invitation to explore the grand line of nature, the sweeping statement of a landscape rendered by brute force on a planetary scale.

As the bus trundled on, a quick glance at the Ordnance Survey underlined the daunting beauty of the terrain. Feinne-Bheinn Nhor, Coigach, Cul Mor, Quinag and Suilven; the names of draughty peaks came howling from the map like disconsolate wails. Lochs Glendhu, Borralan, Urigill, Culag and Bad a´Ghail sound like place names lifted from Tolkein, but the scenery outside the bus is of even more epic proportions. Even a lone stag, picturesquely framed on the skyline like a commercial for whisky, water or life assurance, fails to draw my eye for long before it is pulled back to the matter in hand, the potency of the land itself.

West of the road that connects Inchnadamph, Stronchrubie and Knockan Crag, that power begins to becomes apparent. Here lies the basement rock of Britain – a slab of crust two thirds the age of the planet on which the entire edifice of Scpotland is presumed to rest. Formed deep within the Earth around three billion years ago, these rocks – the Lewisian Gneisses – are exposed here on open rolling moorlands, punctuated by countless lochs, lochans and Scottish puddles with the odd mountain towering incongruously above.

Donald points here and there as he tells countless stories from the Highlands. Of bank robbers holed up in isolated shacks; the village bobby turned part-time poacher; and the old lady from Caithness who fought off a military rescue team with a broom during the 1947 blizzard because she believed they were from another planet. In a sense she was right – in that they were from planet Earth – I feel that I am somewhere distinctly different, disconnected from the real world as if in a fantasy novella.

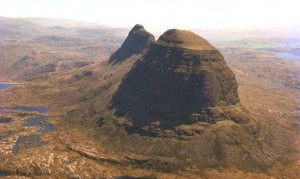

Having arrived in this ancient landscape, I’m surprised that it feels so old and can’t account for the intuition. Near the west coast fishing port of Lochinver, a mountain the rough shape of a policeman’s helmet – Suilven – rises from the moorland like an ancient sentinel and radiates a primordial quality over the whole scene; I half expect to see a diplodocus in Loch a´Choireachin, but have to be content instead with a pair of Goldeneye and a bright yellow rubber duck thrown in by some local wag.

Like other mountains that poke up from the gneiss, Suilven is sandstone formed in great lakes and rivers when this part of Scotland straddled the tropics a billion years ago. Now they have been scoured, worn down by wind, rain and glaciers, the gneiss is left between the peaks, displaying the contours of a landscape from a billion years ago; scenery exhumed from a time when there were no complex organisms on the planet – when even the diplodocus was a distant and unlikely possibility.

And what of the rock that I have travelled so far to see? From a distance it looks a little like granite, but at close quarters it has a distinctive, banded appearance. In places, the stripes twist and turn, squeezed this way and that under monumental force as if the rock once had the structural integrity of toothpaste. There are apparently pink varieties elsewhere, but that’s all another fine and inconsequential detail in the broad sweep of our planet’s history.

Just finished page 120 Ian, a cracking good read, uncluttered, informative, interesting side roads into history and not adorned with scientific turn-off speak. Ten out of ten and for me a walk down memory lane, first discovered and climbed Sullivan, during the 1959 Skye expedition, weather bad, carried on further north, 1x TC MG, 1x 1938 Morgan, 1 X DKW motorbike, five Geordies and thirty seven pounds ten and sixpence.

You are right about the Inaccessible Pinnacle spoiling the Munro baggers breakfast, hilarious, more white eyed white knuckle jobbies on that than there are in the Aiguille du Midi téléphérique.

I have meant to ask, how many pints of milk did you sell?

“Inchnadamph, Stronchrubie and Knockan Crag” The scottish certainly have some great place names!

I’ve always wanted to go to Scotland, I hope to visit it someday! (the knoydart peninsula to be precise)

Is gneiss the stuff that curling stones are made out of??

Curling staines worm, staines, ken?